- Artist

- Hannah Wilke 1940–1993

- Medium

- Lithograph on paper

- Dimensions

- Support: 294 × 231 mm

frame: 524 × 422 × 33 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 2008

- Reference

- P79357

Summary

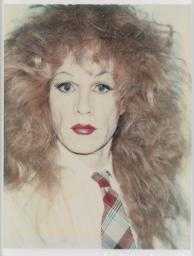

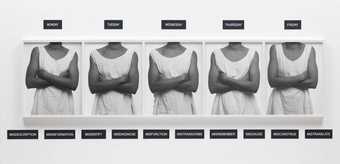

Wilke made the poster Marxism and Art: Beware of Fascist Feminism in response to an invitation in 1975, from the Center for Feminist Art Historical Studies (Los Angeles), to create a work of art for a project entitled What is Feminist Art? It was included in the exhibition of that name at the Women’s Building, Los Angeles in 1977. It is a small black and white print in which the title words sandwich a photograph of the artist challenging the viewer with a confrontational pose. Her shirt opened and thrust aside to reveal her naked shoulders, breasts and stomach above low-slung jeans, she stands staring at the viewer with her hands on her hips and a knowing, half-smile on her lips. Hanging between her breasts and over her bare stomach, a large garishly patterned tie stages a joke phallus knotted around her neck. Small bumps incongruously dot her face and torso like diseased growths: these are her signature chewing gum wounds or, in her words, ‘cunts’.

The photograph is one of a series of approximately fifty ‘performalist’ self-portrait photographs collectively known as the S.O.S. Starification Object Series (1974-82). These feature the artist topless, satirising the poses of glamour models in women’s magazines using a range of props including sunglasses, a cowboy hat and toy guns, rollers, a silk turban and a plastic toy. In all the pictures, Wilke is dotted with the gum wounds which ‘starify’ her, transforming her into a star at the same time as emphasising her scarred or wounded state. The regular and symmetrical placement of the wounds recall the African ritual of scarification in which bodies are ritually scarred, usually as a means of marking a developmental rite of passage. Wilke’s ‘starification’ thus hints at a ritual scarring process necessary to become a female star. In her public performances of this work, documented indirectly by the photographs, Wilke would hand sticks of gum to visitors as they entered the gallery space, before removing her shirt. She would then request the chewed gum from her audience, twisting each piece into a vagina form and sticking it to her bare skin, thus marking herself with a sign. She commented: ‘I chose gum because it’s the perfect metaphor for the American woman – chew her up, get what you want out of her, throw her out and pop in a new piece’ (quoted in Avis Berman, ‘A Decade of Progress, But Could a Female Chardin Make a Living Today’, Art News, vol.79, no.8, October 1980, p.77).

Knowing verbal puns run throughout Wilke’s oeuvre, subverting phallocentric stereotypes by transforming them into terms of female eroticism. Thus, in Wilke’s vocabulary, penis envy becomes Venus Envy (the title of a series of Polaroid images created in 1981 with British artist Richard Hamilton) and, in response to the famous wit of Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) who dubbed himself Salt Seller (in French ‘marchand du sel’, an anagram of his name), Wilke presented herself as ‘sugargiver’. Her work sought to question and disrupt visual prejudice, as words from her 1977 video performance Intercourse with ... elucidate:

As an American girl born with the name Butter in 1940, I was often confused when I heard what it was like to be used, to be spread, to feel soft, to melt in your mouth. To also remember that as a Jew, during the war, I would have been branded and buried had I not been born in America. Starification-scarification /Jew, black, Christian, Moslem ... Labelling people instead of listening to them ... judging according to primitive prejudices. “Marks-ism” and art. Fascistic feelings, internal wounds, made from external situations. Sticks and stones break our bones, but names more often hurt us.

(Quoted in Frueh, pp.139 and 145.)

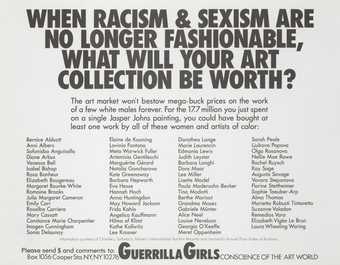

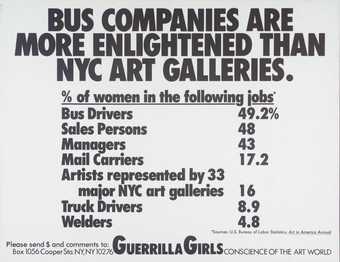

Wilke had a difficult relationship with the feminist movement in the 1970s as a result of her uncompromisingly glamorous self-presentation and the confrontational use of her nude body in her work, which by many was seen dismissively within the narrow prism of narcissism. Marxism and Art is a response to such critics as the well-known feminist Lucy Lippard (born 1937) who, in 1976, accused her of flaunting her body and confusing her role as a beautiful woman with that of an artist resulting in ‘politically ambiguous manifestations’ (quoted in Hannah Wilke: Exchange Values, p.160). In the poster Wilke makes the point that prejudices against traditional ideals of femininity or feminine beauty may come from women as much as from men; that a feminism that prescribes how a woman should look or behave is as harmful as the objectifying values that feminism seeks to redress. In 1980 she explained: ‘While feminism in a larger sense is intrinsically more important that art, the individual remains superior to any system or dogma ... In the narrow politics of feminism, art is only a weapon, which may endanger women’s art that is formally and humanly relevant but does not adhere to a specific political or commercial concept ... Beware of Fascist Feminism. There is an ethics as well as a warning in esthetic ambiguity.’ (Quoted in Avis Berman, ‘A Decade of Progress, But Could a Female Chardin Make a Living Today’, Art News, vol.79, no.8, October 1980, p.77.)

Wilke first used the vulva in her work as early as 1959, when she was studying fine art at Temple University, Philadelphia. It later became her signature motif in drawings, prints, terracotta, ceramic, lint and latex sculptures as well as the tiny forms made from kneaded erasers and chewed gum. As a counter to the symbol of the phallus, it was taken up by the women’s movement in such celebrated works as Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1974-9), a monumental installation of ceramic vagina dinner plates. For Wilke, the art historical and psychoanalytic associations of the vagina as wound made it the ideal image to speak of forms of prejudice inherent to visual language.

Marxism and Art: Beware of Fascist Feminism was printed in two editions. Tate’s is the tenth in a deluxe edition of twenty-five. In an act of deliberate provocation, Wilke posted a group of posters (from an unnumbered disposable edition) on a screen outside the prestigious Leo Castelli Gallery, New York that same year.

Further reading:

Hannah Wilke: Exchange Values, exhibition catalogue, Artium de Álava, Centro Museo Vasco de Arte Contemporaňeo, Vitoria-Gasteiz 2006, pp.159-60, reproduced pp.25 and 89.

Debra Wacks, ‘Naked Truths: Hannah Wilke in Copenhagen’, Art Journal, vol.58, no.2, summer 1999, pp.104-6.

Joanna Frueh, Thomas H.Kochheiser, Hannah Wilke: A Retrospective, exhibition catalogue, Gallery 210, University of Missouri-St Louis, Missouri 1989, p.47, reproduced pp.40 and 46.

Elizabeth Manchester

September 2008

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- photographic(4,673)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- tie(149)

- chewing gum(3)

- poster(874)

- breast(103)

- sexual organs(178)

- wounded(135)

- Jewish(3,752)

- dress: fantasy/fancy(506)

- eroticism(409)

- inscriptions(6,664)

-

- printed text(1,138)

- trading and commercial(1,154)