- Artist

- Jeff Wall born 1946

- Medium

- Transparency on lightbox

- Dimensions

- Object: 2500 × 3970 × 340 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with assistance from the Patrons of New Art through the Tate Gallery Foundation and from the Art Fund 1995

- Reference

- T06951

Summary

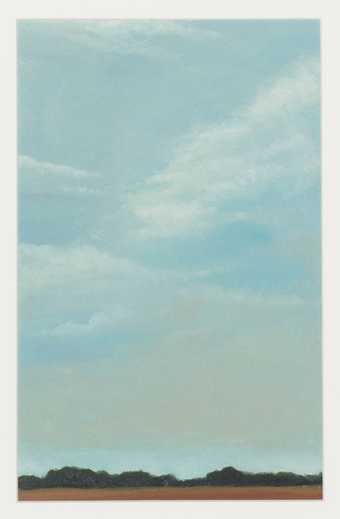

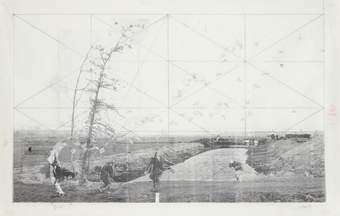

A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai) is a large colour photograph displayed in a light box. It depicts a flat, open landscape in which four foreground figures are frozen as they respond to a sudden gust of wind. It is based on a woodcut, Travellers Caught in a Sudden breeze at Ejiri (c.1832) from a famous portfolio, The Thirty-six Views of Fuji, by the Japanese painter and printmaker Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849). Wall photographed actors in a landscape located outside his home town, Vancouver, at times when similar weather conditions prevailed over a period of five months. He then collaged elements of the photograph digitally in order to achieve the desired composition. The result is a tableau which appears staged in the manner of a classical painting. As in Hokusai’s original, two men clutch their hats to their heads while a third stares up into the sky, where his trilby is being carried away by the wind. On the left, a woman’s body is halted in a state of shock, her head concealed by her scarf which has been blown around her face. A sheaf of papers in her hand has been dispersed by the gust and their trajectory, over the centre of the image, creates a sense of dynamic movement. Two narrow trees, also in the foreground, bend in the force of the wind, releasing dead leaves which mingle with the floating papers. In Hokusai’s image the landscape is a curving path through a reed-filled area next to a lake, leading towards Mount Fuji in the far distance. In Wall’s version, flat brown fields abut onto a canal. Small shacks, a row of telegraph poles and concrete pillars and piping evoke industrial farming. The unromantic nature of the landscape is reinforced by a small structure made of corrugated iron in the foreground. The pathway on which the figures stand is a dirt track extending along the front of the photograph from one side to the other. There is no sense of connection between the characters, whose position in the landscape appears incongruous. Two wear smart city clothes, adding to the sense of displacement.

Wall trained initially as a painter at the University of British Colombia, Vancouver. After completing an MA in 1970, he moved to London to undertake doctoral research in art history at the Courtauld Institute (completed 1973) and became interested in film, working on collaborative film projects and producing his own feature film scripts. In 1977, after a break of nearly seven years, he returned to the studio with an idea for a new, hybrid form of art. He explained:

I felt very strongly at that time that ... painting as an art form did not encounter directly enough the problem of the technological product which had so extensively usurped its place and its function in the representation of everyday life ... I remember being in a kind of crisis at the time, wondering what I would do. Just at that moment I saw an illuminated sign somewhere, and it struck me ... that here was the perfect synthetic technology for me. It was not photography, it was not cinema, it was not painting, it was not propaganda, but it has strong associations with them all ... It seemed to be the technique in which this problem could be expressed, maybe the only technique because of its fundamental spectacularity.

(Quoted in Barents, p.99.)

The large-scale photographic transparency displayed in a light box became Wall’s signature medium. In early works such as The Destroyed Room 1978 (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa) and Picture for Women 1979 (Musée Nationale d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris) Wall referred directly to old master paintings – The Death of Sardanapalus 1827 (Musée du Louvre, Paris) by Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) and A Bar at the Folies-Bergères

1881-2 (Courtauld Institute, London) by Edouard Manet (1832-83) respectively. Wall’s contemporary restaging added a subversive political undercurrent, resulting from the influence of feminism on his reading of theoretical texts. Subsequent works continue to represent the subjects of the traditional ‘painted drama’ – actors as models arranged in constructed tableaux - using contemporary technology and landscapes. They remain politically engaged. However, Wall quickly moved away from overt references to classical painting and began to depict scenes he had witnessed on the street. Instead of photographing these ‘spontaneous moments’ in the manner of reportage, Wall used them as starting points for his own image. In the late 1980s his subject matter began to shift from events he had seen to scenes from his imagination and dreams. At the same time the suggested narrative present in the earlier images was replaced by an allegorical dimension. In the early 1990s Wall began to use digital manipulation to collage photographic constituents, heightening the contrast between the real and the fictional. Collaging elements from a range of sources was standard practice in the making of a classical painting. For Wall, applying this technique to photographic material is a process akin to cinematography. In common with film, the image on a light box relies on a hidden space from which light emanates to be seen. Wall believes that this inaccessible space produces an ‘experience of two places, two worlds in one moment’, providing a source of disassociation, alienation and power (quoted in Barents, p.99).

Study for ‘A Sudden Gust of Wind (After Hokusai)’ 1993 (Tate T07235) reveals something of Wall’s working process on paper.

Further reading:

Else Barents, Jeff Wall: Transparencies, Munich 1986

Jeff Wall, exhibition catalogue, Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art, Galerie Nationale du Jeu de Paume, Paris, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1995, pp.14-15, reproduced p.61 in colour

Kerry Brougher, Jeff Wall, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles 1997, pp.26 and 34, reproduced pp.124-5 in colour

Elizabeth Manchester

July 2003

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- architecture(30,960)

-

- bridges and viaducts(4,123)

-

- bridge(3,989)

- industrial(2,075)

-

- canal(589)

- townscapes / man-made features(21,603)

-

- telegraph pole(103)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- photographic(4,673)

- artifice(96)

- environment / nature(315)

- reading, writing, printed matter(5,159)

-

- paper(80)

- Canada(54)