- Artist

- William Tucker born 1935

- Medium

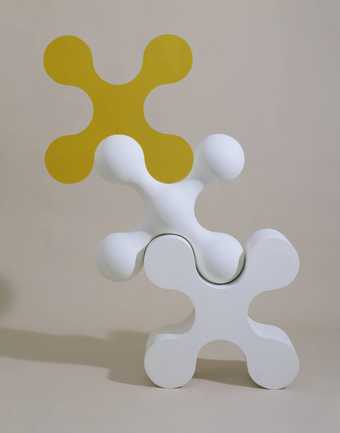

- Painted fibreglass and steel

- Dimensions

- Object: 1124 × 781 × 413 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by Alistair McAlpine (later Lord McAlpine of West Green) 1970

- Reference

- T01372

Catalogue entry

William Tucker b. 1935

T01372 Margin I 1962

Not inscribed.

Painted fibreglass and steel, 44¼ x 30¾ x 16¼ (112.5 x 78 x 41.5).

Presented by Alistair McAlpine 1971.

Coll: M. E. Cooke, Bangor, Wales; Alistair McAlpine.

Exh: Rowan Gallery, July 1963 (6); New Generation, Whitechapel Art Gallery, March–April 1965 (28); The Gregory Fellows, Leeds City Art Gallery, November–December 1969 (4); The Alistair McAlpine Gift, Tate Gallery, June–August 1971 (36, repr.).

Lit: Ian Dunlop, catalogue of New Generation, Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1965, pp. 65–6; Richard Morphet, in catalogue of The Alistair McAlpine Gift, 1971, pp. 89–105.

The notes on all acquisitions of sculpture by Tucker from ‘T01372 to T01380 inclusive are based on the compiler’s conversations with the artist in 1971 and were approved by him. They are quoted or adapted here from the text of the catalogue of The Alistair McAlpine Gift at the Tate Gallery in 1971.

‘Margin I’ is a unique piece.

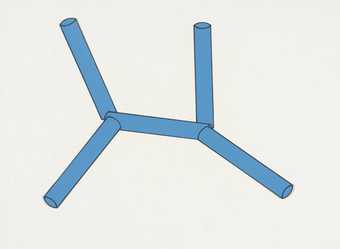

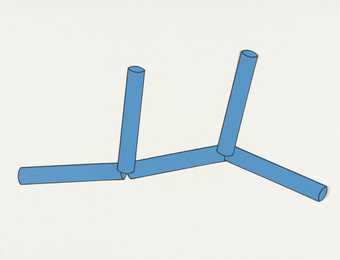

Like David Smith, Tucker conceived early works such as ‘Margin I’, ‘Margin II’ and ‘Unfold’ on a flat surface; their three-dimensional qualities were developed directly from and were dependent upon the flat action, akin to drawing, of cutting into steel or aluminium. In ‘Margin I’ an abstract outline was drawn on a blackboard, next transposed first into flat steel, then into a three-dimensional projection of the kind of volume the outline seemed to imply. Simply bolted together edge to edge and opposite ways up, the flat and volumetric elements demonstrate their likeness and dissimilarities and their calculated step-by-step evolution with almost banal directness; yet they make, from any aspect, a mysterious previously unknowable formal whole that seems almost to have sprung from nowhere. The contrast of views alternates strangely between full silhouette and apparent volume; and from the organic broadside view to the purely geometric view from above, to the end view combining rippling trunk with crisply-formed half-ovals. Yet all these views are immediately grasped from any single aspect. Colour has a purely functional role in establishing tonal equivalence between the parts while yet making clear their distinctness.

Published in The Tate Gallery Report 1970–1972, London 1972.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- colour(2,481)

- irregular forms(2,007)