- Artist

- Jon Thompson 1936–2016

- Medium

- Acrylic and oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 1780 × 1527 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 2019

- Reference

- T15198

Summary

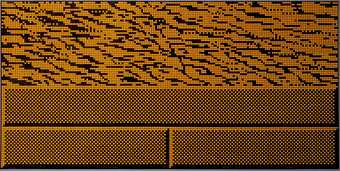

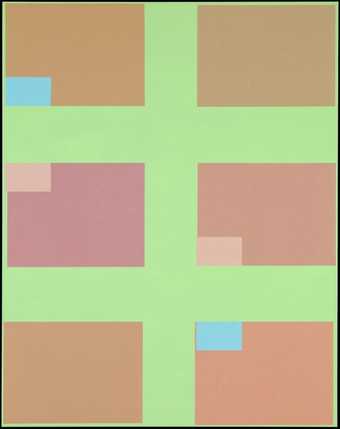

The Toronto Cycle #10 – Absent Roots Three Fold 2009 is a portrait-format abstract painting in oil on canvas. The dominant motif at first appears to be a field made up of irregular zigzag horizontal lines, coloured alternately red and green. These lines are painted on a grey ground that appears as a thin line both around the border of the painting and also between each zigzag line. These irregular zigzags are disrupted by three lines (the ‘Three Fold’ of the title); one positioned horizontally but curved upward in the bottom fifth of the painting, another horizontal but dipping downwards in the upper fifth of the painting – both of which extend the full width of the painting; and one vertically (off-square) down the middle of the painting joining both of the curving lines. Each of these cuts or ‘folds’ creates a rupture so that the zigzags are not continuous across the painting but appear displaced by the folds.

Thompson’s Toronto Cycle of paintings is an indication of how he had been profoundly affected by the recordings and the writing of the Canadian pianist Glenn Gould; the title of the series of paintings refers to Gould’s hometown of Toronto. Thompson drew many parallels between Gould’s approach to musical interpretation and expression and his own approach as a painter. He reflected that,

Gould’s idea of repetition through translation – the building of an imaginal entity, capable of taking passage from the inside to the outside followed by the translation of mental ‘stuff’, ‘the music itself’, into a perceivable form, is not unfamiliar to painters … Colour, mood, atmosphere, sense of place are all factors which come to exist in my mind’s eye in an utterly compelling and extremely precise form.

(Jon Thompson, ‘The Thing Itself’, cited in Jon Thompson Toronto Cycle, press release, Anthony Reynolds Gallery, London 2009.)

When The Toronto Cycle #10 – Absent Roots Three Fold was first exhibited at Anthony Reynolds Gallery in London, Thompson included in the gallery a passage written by Gould about the music of the classical composer Ludwig van Beethoven:

Beethoven was actually playing with absent roots … roots that were not actually sounded in all cases but which produced an absolute mathematical correspondence … Drawing on the teaching of [the music theorist Simon] Sechter … [one] could have a certain cluster [of notes] and there would be one note absent from it that was the key to its function as a cluster, the key to where it was going and point from which it had come.

For Thompson’s painting, the ‘absent root’ was both the fourth colour that appears as an afterimage between the complementary red and green zigzags as well as the way in which the folds disrupt the jagged pattern but, in so doing, suggest an idea of a larger totality. For the artist and critic Sherman Sam, ‘they could be folds in time, they are certainly folds in logic, but they are not matter-of-fact, as in Stella’s “what you see is what you see.” Rather, Thompson’s thinking, I believe, allows an element of time to enter and thus contradicts the presentness of this hard-edge language.’ (Sherman Sam, ‘Letter from London: Jon Thompson, Paintings from The Toronto Cycle’, The Brooklyn Rail, December 2009, https://brooklynrail.org/2009/12/artseen/letter-from-london-jon-thompson-paintings-from-the-toronto-cycle, accessed 30 October 2018.)

Thompson began his career as an artist in the early 1960s, making abstract paintings before turning to a less studio-based practice of conceptual photography and object-based installation (see, for example, his diptych photographic self-portrait Untitled 1997 [Tate T07402]). A respected tutor for many years, particularly at Goldsmiths College in London, he became celebrated for opening-up specialisms and allowing students to move freely between different disciplines – a reflection of his approach to his own work since stopping painting. His retirement from teaching in 2005 was marked by a return to abstract painting that was prefaced by a number of years when he was preoccupied with thinking about painting, during which time he came ‘to believe that painting offers the highest order of aesthetic experience, an intimation of “oneness” or singularity. When a painting really works, it has answered the oldest of metaphysical conundrums by becoming more than the sum of its parts.’ (Jon Thompson, untitled unpublished text, 2005, Tate catalogue file.) This particular painting, as well as the slightly later Simple Paintings (Thinking About Signorelli) 2012–13 (Tate T1519), exemplifies the hermetic nature of his painting in which seemingly rational spatial compositions are disrupted both structurally or by a suggestive use of colour.

Further reading

Jeremy Akerman and Eileen Daly (eds.), The Collected Writings of Jon Thompson, London 2011.

Andrew Wilson

October 2018

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.