- Artist

- John Stezaker born 1949

- Medium

- Postcard on paper on photograph, black and white, on paper

- Dimensions

- Unconfirmed: 240 × 190 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 2007

- Reference

- T12346

Summary

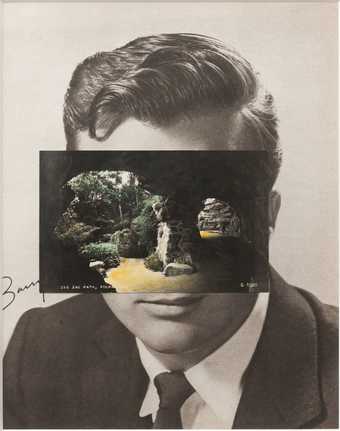

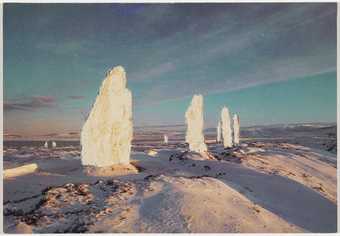

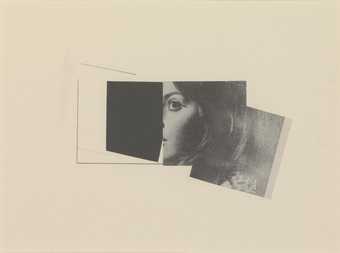

Mask XIII is a collage created by superimposing a postcard on a black and white photograph. The photograph is a film publicity portrait of an unidentifiable actress taken during the 1940s or 1950s. The postcard is a colour print mounted upside down over the actress’s face. It shows an image of a ruined stone building partially surrounded by trees. Stezaker has positioned it so that the inverted building appears framed within the actress’s face: the edge of the building matches the actress’s hairline at the right side of her face and a tree trunk and branches continuing the line of her face’s left side. Dark areas of foliage either side of the building align with her dark hair. A second tree in front of the ruin extends down the image to connect with the woman’s hand which is raised to her chin emerging from a narrow section of sky at the top of the postcard. At the bottom of the postcard, which traverses the subject’s forehead, the inverted caption ‘Nîmes – Le Temple de Diane’ identifies the ruin as the temple of Diana at Nîmes in France. The form of the inverted temple and its positioning over the woman’s face have the effect of evoking a skull: three rounded arches leading into darker spaces suggesting eye and nose-sockets and the broken upper edge of the ruin drawing the line of a broken and toothless jaw.

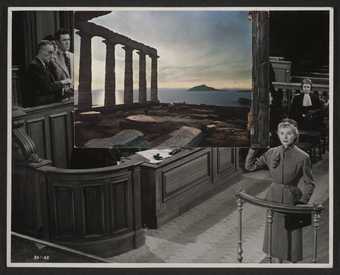

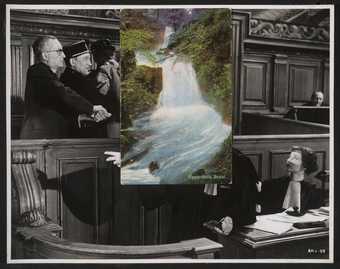

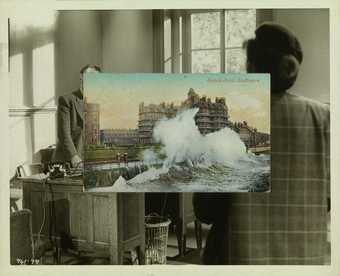

Initiated around 1980, the series of Mask collages developed from the Film Still collages, such as The Trial, The Oath

and Insert (1978-9, T12341-3). The Masks all follow a similar and deceptively simple format: a film publicity portrait of a star whose face is covered by a postcard – ostensibly a mask – which opens a window into another space, paradoxically suggesting a view behind the mask constituted by the actor’s face. Initially the postcards were images of bridges and caves which in some instances united two or more protagonists. Over the years Stezaker has extended his range of imagery to include tunnels, caverns, rock formations such as stalactites and stalagmites, railway tracks, historic ruins and monuments (as in this collage), woodland clearings and paths (as in Mask XIV, 2006, T12347), as well as streams, waterfalls (as in Mask XI, 2005, T12345), lakes and the sea. Stezaker began collecting film stills in 1973 but was not able to afford photographic portraits of film stars until the early 1980s when their price dropped. The first portraits the artist used were damaged or of forgotten film actors, unnamed and anonymous. He has commented:

The Masks were inspired by reading Elias Canetti’s essay on masks and unmasking in his wonderful book Crowds and Power which inspired so much of my work at this time ... I was also teaching a course on Bataille and the origins of art which focused on the mask as the origin and point of convergence of all the arts. Canetti’s idea of the mask as a covering of absence and, in its fixity, as a revelation of death, alongside my discovery of Blanchot’s Space of Literature, was an important turning point in my thinking and in my approach to my work. I usually think of the key dates being 1979 and 1980 as marking a yielding to pure image-fascination and as a release from any function societal or transgressive in the work. The Masks were a response in practice to the Canetti/Blanchot idea of the ‘death’s space’ of the image and consolidated the sense of pure fascination and the desire for ‘exile from life in the world of images’, an ideal I saw in the practice of Joseph Cornell.

(Letter to the author, 26 October 2007.)

Stezaker shares with Joseph Cornell (1903-72) the Surrealist technique of apparently irrational juxtaposition and the evocation of nostalgia through his focus on outdated imagery, collected and pondered over many years. While Stezaker’s use of film stills and publicity portraits of the 1940s and 1950s stems from his boyhood experience of encountering these images on the outside of cinemas advertising films from which he was excluded because of his youth (letter to the author, 26 October 2007), his choice of postcards tends towards the Romantic tradition of nature and the sublime. The artist’s juxtaposition and careful alignment of the postcard image with the publicity portrait create an effect related to the concept of the uncanny as described by Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) in his 1925 essay, ‘The Uncanny’. Freud analysed the feeling of the uncanny aroused most forcefully by the fantastic stories of the Romantic writer E.T.A. Hoffmann (1776-1822), in particular his tale The Sandman (first published in Nachtstücke, 1817). He relates the sense of horror experienced by the protagonist Nathaniel not only to the mechanical doll Olympia, who appears real, but more significantly to a fear of losing ones eyes which he connects to the Oedipal castration complex. In the Masks the subjects’ eyes are covered; the collage intervention substitutes blankness or holes – dark and empty or leading into other spaces – creating the disturbing sensation of seeing death beneath the features of a living being.

The Temple of Diana shown in Mask XIII has romantic resonances that stem from a mistaken attribution. A Greco-Roman ruin dating from approximately the second century AD, it is believed that the building was incorrectly named during excavations in the seventeenth century when a statue of Diana, the Roman goddess of the hunt, was found in the ruins. It is not known what the true purpose of the building was, but it is likely that it was related to the Fountain sanctuary built by the Romans under the Emperor Augustus (63BC-AD14) to make holy water from a spring available all year round. The image thus relates to the notion of the source, central to the iconography of Stezaker’s Mask XI.

Further reading:

John Stezaker: Marriage, exhibition catalogue, The Approach W1, London 2008.

Mark Coetzee, John Stezaker: Rubell Family Collection, exhibition catalogue, Rubell Family Collection, Miami 2007, pp.17-19 and 57-75.

Michael Bracewell, ‘Demand the Impossible’, Frieze, issue 89, March 2005, pp.89-93 and front cover.

Elizabeth Manchester

November 2007

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

This work follows a deceptively simple format: Stezaker covers an old publicity portrait of a film star with a postcard. The postcard becomes a mask over the face, but rather than just concealing, it opens a window into another space. This pair of images activates our innate tendency to interpret faces in patterns and imagery. The scene in the postcard could be seen to reflect the interior state of the figure. Alternatively, by replacing eyes with blankness or holes, it might be showing us death beneath the features of a living being.

Gallery label, January 2019

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- figure(2,270)

- periods and styles(5,198)

-

- classical(1,040)

- temple(344)

- religious(849)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- nostalgia(84)

- alignment(6)

- fragmentation(233)

- photographic(4,673)

- music and entertainment(2,331)

-

- cinema(206)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- mask(172)

- postcard(221)

- actions: expressive(2,622)

-

- hiding(48)

- woman(9,110)

- hand(602)

- head / face(2,497)

- individuals: female(1,698)

- France(3,508)

- education, science and learning(1,416)

-

- psychology(176)

- arts and entertainment(7,210)

-

- actor(261)