Sorry, no image available

- Artist

- Dayanita Singh born 1961

- Medium

- 40 photographs, gelatin silver prints on paper and 2 wooden cabinets

- Dimensions

- Overall display dimensions variable

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by the South Asian Acquisitions Committee,Tate Members and Tate International Council 2014

- Reference

- T14176

Summary

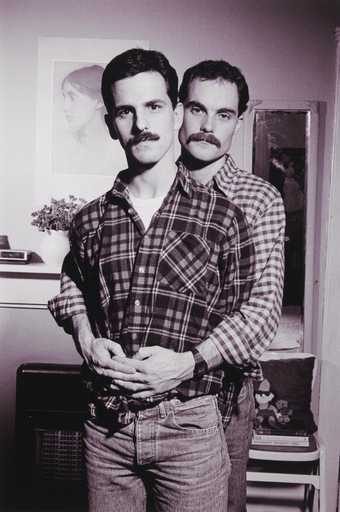

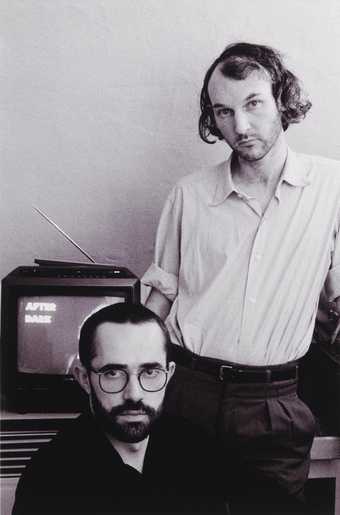

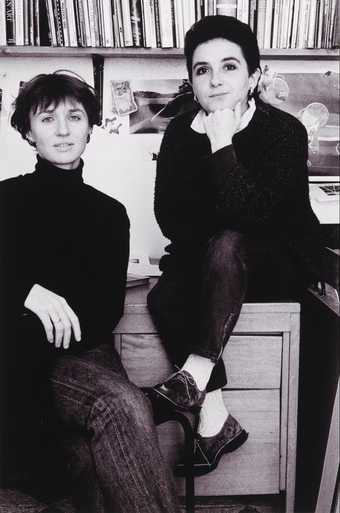

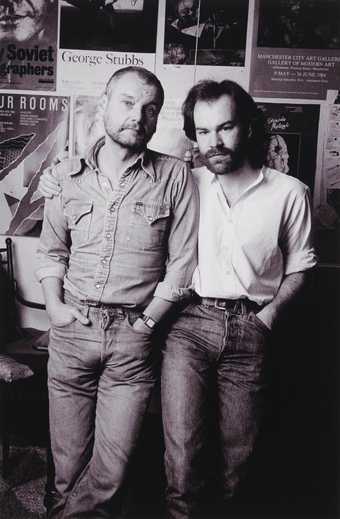

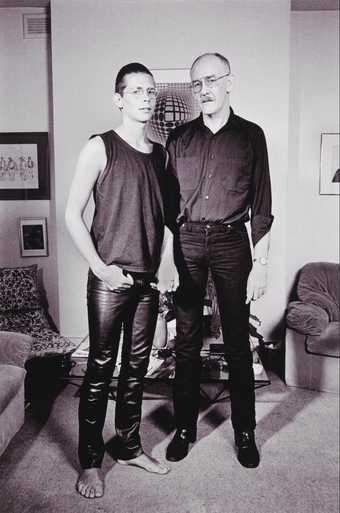

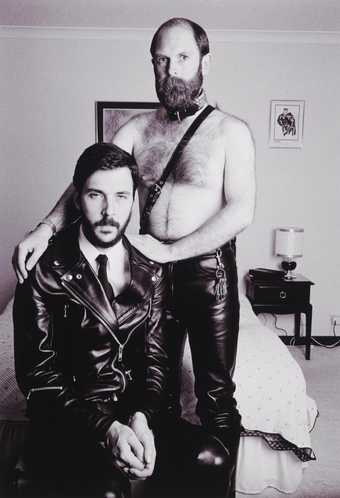

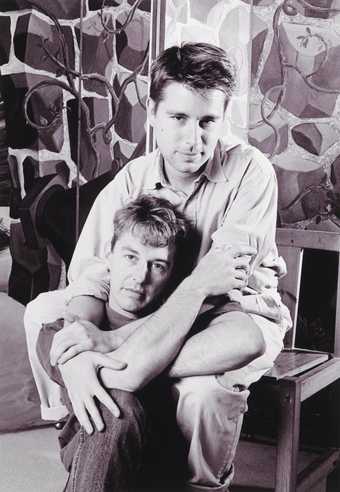

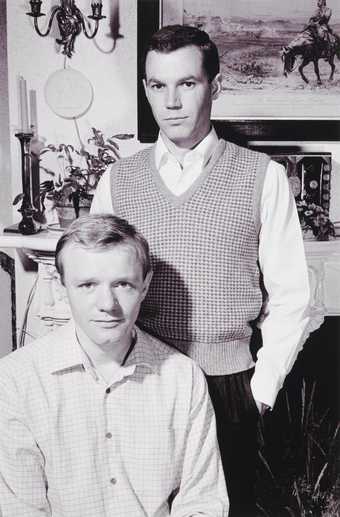

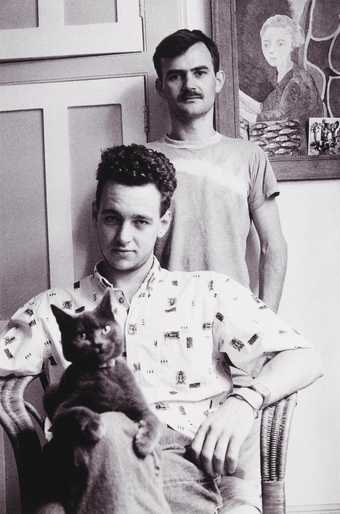

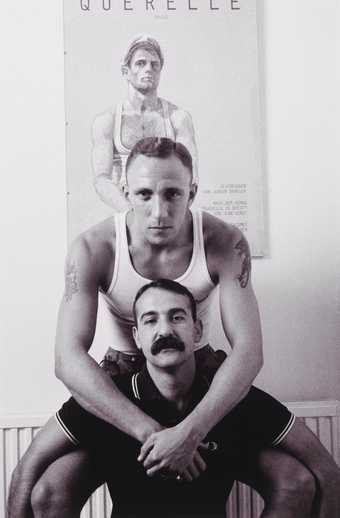

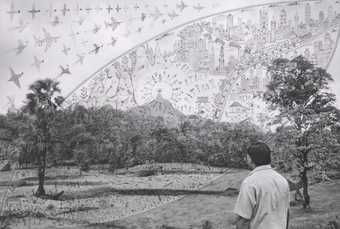

Go Away Closer 2007 is a single work that comprises forty small black and white photographs by the Indian photographer Dayanita Singh; their wood frames and museum-style wooden display cabinets are integral parts of the work and can be arranged in multiple configurations. Singh first exhibited Go Away Closer in 2007 in eponymous exhibitions in Delhi and Mumbai, also publishing a small photobook of the same title that year. The images that make up the work – originally thirty-one and since expanded to forty when the work was editioned – were gleaned from the artist’s archive of photographs taken in India between 2000 and 2006. The expanded work exists in an edition of seven, of which Tate’s copy is number seven. Images from this body of work were shown in the exhibition Where Three Dreams Cross at the Whitechapel in London and Fotomuseum Winterthur in 2010.

The images in Go Away Closer are square, a format Singh frequently uses, preferring the tightness of focus it allows. In this particular sequence, descriptive information is deliberately withheld, and the order of the images does not follow an obvious thematic or narrative progression. Instead the works are linked by mood and stylistic sensibility. Amongst shots of vacant interiors and scenarios that suggest moments of awkwardness, images of empty theatres recur, hinting at an absent audience. In an interview with the critic Emilia Terraciano in 2012, Singh spoke about her interest in the stylistic restraint of texts by writer such as Italo Calvino and Michael Ondaatje as inspiration for ‘withholding’ narrative information in her visual sequences: ‘I take out that one image to disorient you. I am not interested in that complete picture that you can hold on to.’ (Quoted in Terraciano 2012, p.58.)

Each image is open to interpretation: an adolescent girl in school uniform is sprawled across her bed, either asleep or pretending to be; the interior of an apothecary, perhaps, filled with small vials; display cases, empty and full, one holding shells, one a bell jar containing a death mask; a display of the clothes of independent India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, including his trademark round-collared jacket; architectural details, reflections, bourgeois interiors; hunting trophies; a goat on a sidewalk in a curiously elegant pose; the moment at an Indian wedding where the bride embraces her parents, a cinematic cliché but here a genuine and moving moment. In an interview with Jane Rankin-Reid in 2007, Singh explained, ‘It’s nice not knowing where an image is from. I want to experiment with whether people can read images or not.’ (Rankin-Reid 2007, accessed 31 August 2013.) While her subjects are not exclusively female, Singh has worked extensively with women and their families in previous bodies of work. In Myself, Mona Ahmed 2003 she produced an intimate photographic account of the life of a transvestite, and in Privacy 2004, a nuanced view of the privileged lives of the urban upper classes. Objects and interiors were presented in the series Chairs 2006, which included museum interiors such as the Isabella Stewart Gardner museum in Boston, where she was on a residency.

With its paradoxical title, Go Away Closer expresses Singh’s relationship to the making of images, the measure of her close knowledge of – and necessary formal distance from – her subjects. The title also alludes to the witnessing of both progress and decline in fast-changing urban India. Historian and curator Geeta Kapur has written of Singh’s approach: ‘She addresses the subject, or rather the photo-image, that is proximate, concrete and indifferent; that is indexical, immanent, importunate and also already dead in its absolute pastness.’ (Kapur 2010, p.58.) The style of architecture and types of inanimate objects and interiors that Singh records in black and white are imbued with a melancholic sense of the passage of time, and relate to her interest in museology and archiving. Rather than nostalgia, she has an interest in the temporal quality of the photographs and often chooses her subjects in order to capture particular ways of living. Singh resists obvious cultural markers and exoticisation, and most images in the series draw the viewer in and allow for a personal reading based on their own emotional responses to the mood and setting.

Kapur has explained that Singh’s move away from photojournalism in her work was a deliberate strategy to resist the demand to represent the ‘abject face of metropolitan India’ (Kapur 2010, p.59) and make images with an awareness of her class position, expressing the tensions and contradictions this entails:

Like other South Asian photographers of her generation, the move away from documentary photography and photojournalism and towards making more subjective work was a deliberate choice; Singh’s own awareness of photographic strategies and the limitations of straightforward representation evolved. Within this series she pushes the inherent instability of their narrative power. Singh’s play with sequencing and narrative, especially in book form, is informed by the notion of the images being read as text, able to operate on multiple registers based on the level of engagement of the audience.

(Kapur 2010, p.59.)

Further reading

Jane Rankin-Reid, ‘The Ah-ha Nudge’, Tehelka, 20 January 2007, http://archive.tehelka.com/story_main25.asp?filename=hub012007The_Ah-Ha.asp, accessed 31 August 2013.

Geeta Kapur, ‘Familial Narratives and their Accidental Denouement’, in Where Three Dreams Cross, exhibition catalogue Whitechapel Gallery, London and Fotomuseum Winterthur 2010, pp.47–63.

Emilia Terraciano, ‘Monuments of Knowledge, A Q&A with Dayanita Singh’, Modern Painters, July/August 2012, pp.56–9.

Nada Raza

April 2013

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.