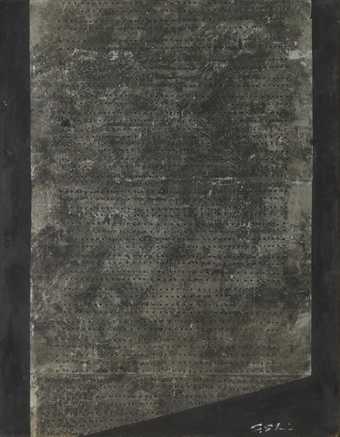

- Artist

- Shozo Shimamoto 1928–2013

- Original title

- Ana

- Medium

- Oil paint on paper

- Dimensions

- Image: 892 × 699 mm

support: 1169 × 912 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the artist 2002

- Reference

- T07898

Summary

Holes is one of a series of works which, according to the artist, was begun either in 1949 or 1950. Created in the artist’s studio in Nishinomiya City, Japan, it was made using a number of sheets of newspaper, topped with a sheet of brown cartridge paper, pasted together with a glue made with flour and water. It was then painted white with hints of pale blue, and its surface was pierced irregularly to reveal the different layers underneath and the painting’s wooden backboard. Viewed from a distance, the overall effect is that of a lunar landscape, all craters and bumps. The contrast between the delicate hues and appealing surface on the one hand, and the violence and destructiveness of Shimamoto’s piercing of the surface on the other, can be said to suggest an interesting relationship between the perceived violence of his work and the qualities of beauty and order prized in traditional Japanese culture.

In a letter of 16 July 2002 to Tate, the artist revealed that he had started to paint on supports made of glued newspaper because in the early 1950s he could not afford to purchase canvas. Shimamoto found that the newspaper support would tear if the glue was not entirely dry before he started to paint on his makeshift support, or if the paper he had used was too delicate, and this provided him with the inspiration for his Holes series.

When these works were first exhibited, they were largely ridiculed in Japan but admired by the innovative circles frequented by the artists who would form the Gutai Bijutsu Kyokai (Gutai Art Association) in 1954 under the aegis of the establish painter Jirō Yoshihara (1905-1972). It was Shimamoto, the secretary of the movement, who proposed the name ‘Gutai’, which has been translated into English as ‘embodiment’ or ‘concrete’. The work made by the artists who adhered to the Gutai movement was far from being stylistically uniform, but was typified by an interest in the materials of art and the art-making process itself rather than the finished work. Gutai focused on materials in a way that blurred the distinction between creative and destructive action, through violent manipulation and the ‘actions’ performed by the artists during exhibitions. One such ‘action’ by Shimamoto involved the use of a cannon to shoot glass bottles full of paint at a large sheet of canvas suspended from a tree during the 1956 outdoors Gutai exhibition on the banks of the Ashiya River.

The early 1950s were an important moment, both socially and politically, for Japan: the country was starting to overcome the difficult post-war period and the first efforts at reconstruction were taking place. This had a strong influence on the way that Gutai work was perceived: as Shimamoto has stated, ‘the time was disastrous for us because it was right after the War and we had been defeated. So people didn’t want to see destruction and violence, and they didn’t want to accept what they had done. So what we did was completely neglected by the audience.’ (‘Breakthrough Performance’, pp.41-2.) The artist, however, feels that his work transcends the violent nature of his techniques: ‘Even if my method seems shocking and violent – crushing bottles and shooting cannons at the canvas – because I am an artist my purpose is to make the work beautiful, to show the beauty of everything. I’m just working on creating beauty.’ (‘Breakthrough Performance’, p.42.)

Although the Gutai movement was felt to be somewhat isolated from developments in Western art, there are many points of contact between Gutai work and that of the American action painters and the French informel movement. There are striking similarities between Shimamoto’s Holes and the buchi

(paintings with ‘holes’) that Lucio Fontana (1899-1968) started making in Italy in 1949 (see, for example, Spatial Concept 49-50 B4, 1949-50, T03961). Shimamoto insists that neither artist was aware of the other’s efforts in the same direction, and that he and Yoshihara first saw Fontana’s work as late as 1954. In his letter to Tate, Shimamoto described the unwelcome results of this discovery. ‘Yoshihara noticed Lucio Fontana’s works of art that employed holes, “Buchi” and “Tagli” [literally “cuts”], and, though there is no way that anyone can claim that my works came after Fontana’s, Yoshihara said that no matter how much we insisted that mine were created first, no-one would believe me in this backward Oriental countryside in a country that had just lost the war, so he instructed me to stop producing the “Holes” series. Since the dates can be seen on the newspapers I used, we were indeed eventually able to prove that they were created during those earlier years, but that was not until much later.’

Further reading:

Action et émotion, Peintures des années 50: Informel, Gutaï, Cobra, exhibition catalogue, National Museum of Art, Osaka 1985

‘To Challenge the Sun: Exhibitions of the Gutai Art Association, Ashiya, Osaka, Tokyo, 1955-57’, in Bruce Altshuler, The Avant-Garde in Exhibition: New Art in the 20th Century, New York 1994, pp.174-91

‘Breakthrough Performance: A Conversation with Shozo Shimamoto’, Border Crossings, vol.17, no.2, May 1998, pp.41-2

Shozo Shimamoto, exhibition catalogue, Beaconsfield Contemporary Art, London 2001

Giorgia Bottinelli

August 2002

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Holes is made from layers of newspaper. Shimamoto painted the surface white with areas of pale blue. He then pierced it to reveal the different layers underneath. Shimamoto began the series around 1949 or 50. This was during the North American occupation of Japan after the end of the Second World War. The contrast between delicate paintwork and violent holes in its surface may reflect the disruption of traditional Japanese culture as a result of the war. Shimamoto founded the radical artist group the Gutair Association in 1954. Finding a balance between destruction and creativity was a key focus in their work.

Gallery label, August 2020

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- gestural(891)

- irregular forms(2,007)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- defacement(257)

- texture(466)