- Artist

- Anwar Jalal Shemza 1928–1985

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 920 × 710 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 2010

- Reference

- T13333

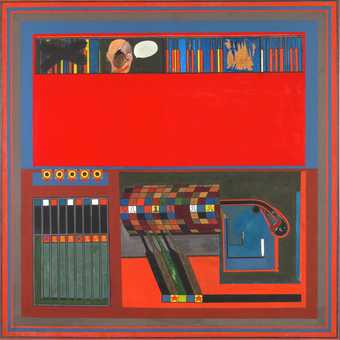

Summary

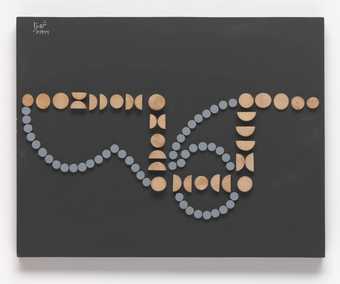

The painting Chessmen One depicts four horizontal rows of black chess pieces which increase in height from the top down. They are set against a lightly textured pale blue background. Each row of chessmen is decorated with sinuous linear detail in different colours, red on the top row, blue on the second, cream on the third and green on the fourth. Each horizontal division between the rows is painted in one of these colours. The chessmen are depicted in a schematic, near abstract frontal view that emphasises the flatness and two-dimensional surface of the canvas.

Shemza, who was born in Simla in India, painted Chessmen One in 1961, the year before he decided to settle permanently in England. Having studied at the Slade School of Art in London in the late 1950s, he travelled to Pakistan with his family in 1960, with the intention of getting a teaching job in Lahore, where he had lived after the partition of India in 1948. In a letter to his friend, the author Karam Nawaz, he explained that the decision to move back to Pakistan had been prompted by the responsibility he felt, as a postcolonial intellectual and artist, towards his own continent. ‘Whatever I have obtained in this country [England],’ he wrote, ‘it was solely for the sake of students in my country.’ (Quoted in Iftikhar Dadi, Anwar Jalal Shemza: Calligraphic Abstraction, exhibition leaflet, Green Cardamom, London 2009, p.3.) However he could not find a teaching post in Pakistan and decided to return to England. He settled in Stafford, his wife’s home town, where he found a teaching post.

During this period, Shemza was investigating the relationship between visual forms and text in his modernist compositions, making reference to Islamic motifs and calligraphic forms. ‘My work’, Shemza wrote in one of his sketchbooks, ‘is based on the simplification of the three dimensional solid, architectural reality and the decorative element of calligraphy.’ (Quoted in Shemza 1989, p.71.) He explored a number of subjects, such as Mughal architecture – particularly the walls and gates of the city of Lahore – prayer carpets, female and plant forms, the letter meem (the Prophet Muhammad’s initial) and chessmen. He worked in series, often producing fifty or more works on one theme before moving to another, and throughout his life he would return to the same theme again and again. He experimented with innovative techniques, and often included in his work references to fabrics, textiles and surface textures. Several of these influences can be discerned in Chessmen One.

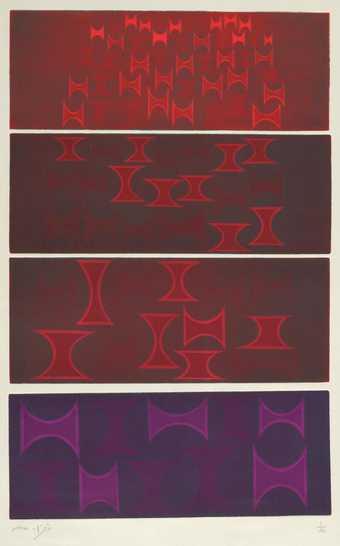

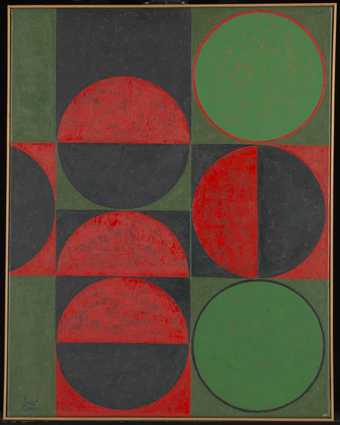

Over the years, Shemza distilled his experiences into a more disciplined formalist practice, much of it based on geometry. For example, on the work One to Nine and One to Seven 1962, he noted in Urdu: ‘A circle – a square – a puzzle – for which a lifetime is not enough’. These simple geometric forms would provide him with a set of limited, yet flexible, building blocks, such as the different form arrangements he explored in his print Forms Emerging 1967 (Tate P79950).

While studying at the Slade between 1956 and 1960, Shemza underwent something of a personal and artistic crisis. Having made a name for himself in Pakistan, he found himself moving from a position of power to one of powerlessness: ‘The “celebrated artist” was lost … as was also the beginner at the Slade. What’s more, I had lost my home. I was an exile, homeless, without a name.’ (Quoted in Hayward Gallery 1989, p.84.) This sense of displacement, and also the fact that his artistic production up to that time meant nothing to the London art scene, prompted him to destroy ‘paintings, drawings, everything that could be called art’. He wondered restlessly from place to place, until he found himself ‘in the Egyptian section of the British Museum. For the first time in England, I felt really at home.’ (Quoted in Shemza 1989, p.67.) His visits to the British Museum allowed him to study Islamic art from various regions and periods, something that he had not been able to do in Pakistan. He also studied the work of Swiss artist Paul Klee (1879–1940). From Klee he learned the importance of the flat surface as a plane for experimentation, and also the freedom to employ abstraction, geometry and pattern towards a modernist exploration.

Shemza was encouraged by his Slade tutor Andrew Forge (1923–2002) in his new experiments. Writing about Shemza’s work for his exhibition at the New Vision Centre in 1958, Forge said:

His paintings derive equally from the rhythmical space-filling patterns of the rug and from the ‘growing line’ of modern Western art. His pictures are not mere patterns but images, and their forms, whether painted or drawn, invest the surface with a mysterious life. They have much of the most characteristic quality of modern art; their content, their mood, the look that they address us with emanates directly from a musical play with simply related forms, from an asymmetrical order, from a sensitive response to the picture surface itself.

(Quoted in Shemza 1989, p.73.)

Further reading

Rasheed Araeen, The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain, exhibition catalogue, Hayward Gallery, London 1989.

Mary Shemza, ‘Anwar Jalal Shemza: Search for Cultural Identity’, Third Text, vol.3, nos.8 and 9, 1989, pp.65–87.

Anwar Shemza, exhibition catalogue, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham 1997.

Carmen Juliá

March 2010

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- man-made(999)

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- irregular forms(2,007)

- sports and games(230)

-

- chess piece(12)