- Artist

- Bridget Riley born 1931

- Medium

- Acrylic paint and oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 1934 × 5820 × 50 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by Tate Members 2003

- Reference

- T11753

Summary

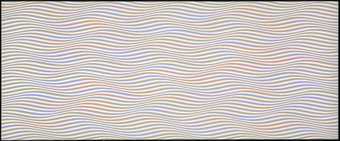

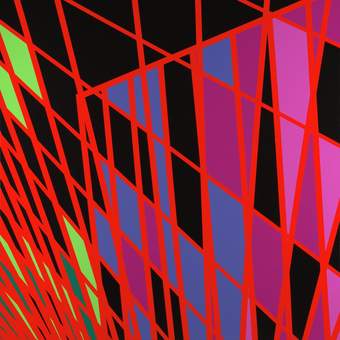

This large painting is a horizontal frieze with irregular curvilinear forms in four clear, vibrant colours: green, blue, light pink and dark pink. To accommodate its size, Riley composed the painting on two abutting canvases. It is one of a number of works using repeated curved forms that Riley began making in 1997. Since her move into pure geometric abstraction in the early 1960s, Riley has worked in series, focussing for several years on a particular formal theme. The curvilinear paintings of the late 1990s and early twenty-first century employ overlapping curved segments, typically in combinations of no more than five colours.

Like other curvilinear paintings, Evoë 3 is structured on a diagonal grid extending from bottom left to top right. The underlying structure gives the composition a forward movement which is tempered by the soft lines of the curves. The basic building blocks for the curvilinear works are curved segments in solid blocks of colour. In Evoë 3 these appear in varying sizes and configurations, from long fluted shapes to cinched arcs. The complex structure of the painting makes it appear as if each colour in turn becomes alternately figure and ground.

The curved shapes recall the outline of leaves or petals, and the sense of movement conveyed in the painting suggests the cadences of ocean waves. Riley has spoken about her great love of nature (see Riley and Bryan Robertson, ‘Things to Enjoy’, Bridget Riley: Dialogues on Art, pp.83-97) and although the forms in Evoë 3 are not directly representational, they suggest shapes and rhythms familiar from the natural world.

In its clear, bright palette and sense of joyous movement, the painting evokes the work of Henri Matisse (1869-1954). The rich colours and sharply delineated forms in Evoë 3 suggest the influence of Matisse’s late cut-outs. The undulating rhythm of Riley’s shapes also recalls images Matisse made throughout his life of dancing figures.

Making analogies with music Riley has described how the rhythm of her curvilinear painting is reliant on the curve. She has said, ‘When played through a series of arabesques the curve is wonderfully fluid, supple and strong. It can twist and bend, flow and sway, sometimes with the diagonal, sometimes against, so that the tempo is either accelerated or held back, delayed’ (quoted in Robert Kudielka, ‘Supposed to be Abstract’, p.26)

‘Evoë’ is a bacchanalian cry. Riley always conceived of this painting as a festive revelry. She has described the genesis of the title of this work, saying, ‘When I had finished Evoë and was thinking about its title I toyed with the idea of calling it “Bacchanal without Nymphs” ... But then I remembered, just in time, that I am after all supposed to be an abstract artist’ (quoted in Kudielka, ‘Supposed to be Abstract’, p.26).

Riley made a previous version of this work, Evoë 1, in 1999/2000. Dissatisfied, she amended it to create this definitive composition, destroying the earlier version.

Further reading:

Paul Moorhouse, ed., Bridget Riley, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London, 2003, reproduced no.56 in colour.

Robert Kudielka, ‘Supposed to be Abstract’, Parkett, no. 61, 2001, pp.22-9.

Robert Kudielka, ed., Bridget Riley: Dialogues on Art, London, 2003.

Rachel Taylor

February 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

In the late 1990s, Riley began to make large-scale paintings in which curved blocks of colour are positioned using an underlying grid of verticals and diagonals, creating a sense of joyous movement. ‘When played through a series of arabesques the curve is wonderfully fluid, supple and strong’, she has said. ‘It can twist and bend, flow and sway, sometimes with the diagonal, sometimes against, so that the tempo is either accelerated or held back, delayed’. The title Evoë was a cry associated with the intoxicated rites of the Greek god Bacchus.

Gallery label, October 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- exhilaration(50)

- pattern(358)