- Artist

- Jackson Pollock 1912–1956

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 1465 × 2695 mm

frame: 1493 × 2721 × 63 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with assistance from the American Fellows of the Tate Gallery Foundation 1988

- Reference

- T03978

Summary

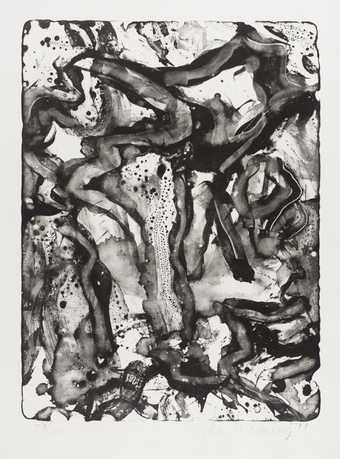

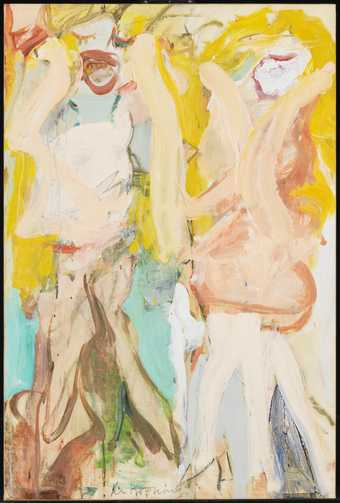

Number 14 is a large unframed oil painting on a horizontally orientated rectangular canvas. The black paint used in this monochromatic painting is applied onto unprimed cotton duck canvas. Impressions of figures appear from the space of the raw canvas, and these can be read as at least two and possibly three horizontal forms and two or three vertical forms. In the upper left and upper right corners of the canvas are the suggestion of eyes, yet the full scene depicted remains ambiguous. The work has had a small patch added by the artist to the upper right-hand corner to cover a tear. It is signed and dated in the lower left-hand corner.

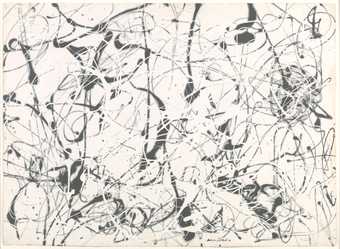

Number 14 was created by the American abstract expressionist artist Jackson Pollock in 1951. He is best known for pioneering action painting, a method of dripping paint onto a canvas laid out on the floor by means of the vigorous action of his body. From 1947 Pollock employed this drip technique to produce colourful and rhythmic abstract paintings, such as Summertime: Number 9A 1948 (Tate T03977). However, after four years of creating these, Pollock moved away from pure abstraction, advancing towards a more figurative and starkly monochromatic practice, as is seen in Number 14. Pollock began to restrain his method of applying the paint to the surface by pouring it rather than dripping. Due to the restricted palette and the method of paint application this series of paintings, created between 1951 and 1954, became known as Pollock’s ‘black pourings’.

Pollock worked with commercially available materials, watering down black industrial enamel to a consistency he could deftly apply. The paint was poured by hand onto a roll of commercial cotton canvas or applied using a syringe, an implement Pollock handled ‘like a giant fountain pen’, according to his partner, the artist Lee Krasner. (Krasner in B.H. Friedman, ‘An Interview with Lee Krasner Pollock’, in Jackson Pollock: Black and White, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, New York 1969, p.8.) Pollock applied the paint from above, circling around the canvas, which he dubbed ‘the arena’. When the paint met the unprimed surface it bled into the weave of the cotton. The critic Lawrence Alloway observed that this blurring effect linked these paintings to the drawings Pollock was also making at the time:

The black, even when applied in a continuous stream, does not produce a strongly directional reading. It burrs at the edges as it leaks out onto the canvas. The effect is somewhat like photographic enlargements of an etched line, in which the irregularities of the edges turn the contours into sensually fraying thresholds. The black line tends to dilate as a mark rather than to converge upon enclosed areas. Thus what looks like drawing is, in fact, a restrained but pervasive way of painting; the black paintings are concerned with the fusion of colour and surface, of paint and field.

(Alloway 1969, p.41.)

In keeping with Pollock’s earlier series, the ‘black pourings’ were titled by number, allowing the viewer scope to form their own interpretation of the work’s subject. The individual paintings in the series were cut from the roll of canvas once completed. A photograph taken in Pollock’s studio by Hans Namuth in late 1951 shows Number 14 on the same piece of cloth as Number 10 1951. This method of painting several works onto a continuous stretch of canvas provides a possible explanation for the splashes of red, green and yellow along the bottom edge of Number 14 and a reddish stain towards the centre. It seems unlikely that these were deliberately applied but they appear to have been intentionally retained.

Pollock exhibited this series of paintings in early 1952 and they formed his last major body of work before his death four years later. Within the series, Number 14 was particularly well received by Pollock’s contemporaries, with critic Clement Greenberg writing, ‘“Fourteen” and “Twenty-Five” in the recent show represent high classical art: not only the identification of form and feeling, but the acceptance and exploitation of the very circumstances of the medium of painting that limit such identification’ (Greenberg, ‘Art Chronicle: Feeling is All’, Partisan Review, January–February 1952, p.102). The series was not met with the universal acclaim afforded the drip paintings, but many contemporary critics welcomed Pollock’s bravery in revisiting the figurative, which had shaped his early practice, a period of his career represented in Tate’s collection by Naked Man with Knife c.1938–40 (Tate T03327). For Greenberg, the slower rhythm and ambiguity of the ‘black pourings’ represented ‘a turn but not a sharp change of direction; there is a kind of relaxation, but the outcome is a newer and loftier triumph’ (Greenberg 1952, p.102).

Further reading

Lawrence Alloway, ‘Pollock’s Black Paintings’, Arts Magazine, vol.43, May 1969, pp.40–4.

The Tate Gallery 1984–86: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions Including Supplement to Catalogue of Acquisitions 1984–86, Tate Gallery, London 1988, pp.238–45, reproduced p.238.

Gavin Delahunty, Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots, London 2015.

Phoebe Roberts

May 2016

Supported by the Terra Foundation for American Art.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

By 1951, Pollock had achieved considerable success with his dripped and poured abstract painting. He was widely regarded as the leading young North American artist. Perhaps fearing that he was reaching a dead-end in his work, he embarked on a series of black and white paintings in which figures emerge, as they had in his early works. After rolling the canvas out on the floor, he would apply the paint – usually industrial enamel paint – with sticks and basting syringes. The artist Lee Krasner, who was married to Pollock, recalled him wielding these ‘like a giant fountain pen’.

Gallery label, October 2019

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Jackson Pollock

1912-1956

T03978 Number 14

1951

Enamel paint on canvas 1456 x 2695 ' (57⅝ x 106⅛)

Inscribed 'Jackson Pollock 51' b.I.,

'Jackson Pollock 51' on stretcher t.l. and 'No. 14 100W x 57½ H 1951'

Purchased from the estate of the artist's widow Lee Krasner Pollock (Grant-in-Aid) with assistance from the American Fellows of the Tate Gallery Foundation 1985-8

Prov: Given by the artist to Lee Krasner Pollock (died 1984) after 1951

Exh: Jackson Pollock 1951, Betty Parsons' Gallery, New York, Nov.-Dec. 1951 (repr. [p.16]); Jackson Pollock, Paul

Facchetti, Paris, March 1952 (no number, repr. [p.1]); Jackson Pollock, Museum of Modern Art, New York, Dec. 1956-Feb.1957 (28, repr.); Pollock, IV Biennial, São Paulo, Sept.-Dec. 1957 (24); Jackson Pollock 1912 -1956, tour under the auspices of the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Museo nazionale d'arte moderna, Rome, March 1958 (23 as 'Numero 14'), Kunsthalle, Basle, April-May 1958 (23 as 'Nummer 14'), Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, June-July 1958 (23 as 'Nummer 14'), Kunsthalle, Hamburg, July-August 1958, (23 as 'Nummer 14'), Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Berlin, Sept.-Oct. 1958 (21 as 'Nummer 14'), Whitechapel Art Gallery, Nov.-Dec. 1958 (21); Jackson Pollock et la nouvelle peinture americaine, tour under the auspices of the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Musée national d'art moderne, Paris, Jan.-Feb. 1959 (21 as 'Numero 14'); Documenta II, Museum Friedericianum, Kassel, July-Oct. 1959 (9); Jackson Pollock, Kunsthaus, Zurich, Oct.-Nov. 1961 (98); Jackson Pollock, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Feb.-April 1963, (84 as 'Nr. 14'); Jackson Pollock, Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, New York, Jan.-Feb. 1964 (116, repr.); Bilanz International, Kunsthalle, Basle, June-Aug. 1964 (110, repr.); Man: Glory, Jestand Riddle, San Francisco Museum of Art, Nov. 1964-Jan. 1965 (276, repr.); Jackson Pollock, Museum of Modern Art, New York, April-June 1967 (60a, repr.); Jackson Pollock: Black and White, Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, New York, March 1969 (10, repr.); Jackson Pollock, Musée national d'art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, Jan.-April 1982 (no number, repr. p.186 in col.); on loan to Tate Gallery April 1982-April 1985; Forty Years of Modern Art 1945 -1985, Tate Gallery, Feb.-April 1986 (not in cat.); Polo Ball, White Birch Farm, Greenwich, Connecticut, 19 Sept. 1987 (no cat.)

Lit: Clement Greenberg, 'Art Chronicle. Feeling is All', Partisan Review, Jan.-Feb. 1952, p.102; Sam Hunter, 'Jackson Pollock', Museum of Modern Art, New York Bulletin, Vol.24, no.2, 1956-7, p.11, repr. pp.10 and 30; Richard Smith, 'Jackson Pollock 1912-1956', Art News and Review, vol.10, Nov. 1958, p.5; Frank O'Hara, Jackson Pollock, New York 1959, p.30, pl.65; Friedrich Bayl, 'Jackson Pollock', Die Kunst und das schöne Heim, vol.9, June 1961, p.330, fig. 1; B.H. Friedman, Jackson Pollock: Energy Made Visible, New York 1972, p.191; F.V. O'Connor and E.V. Thaw (eds.), Jackson Pollock: A Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, Drawings and Other Works, New Haven and London, 1978, II, p.154, no.336 repr. and IV, p.261, fig 67; Francis V. O'Connor, 'Jackson Pollock: The Black Pourings' in Jackson Pollock: The Black Pourings 1951-1953, exh. cat., Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston 1980, p.22 repr.; Wolfgang Sauré, 'Pariser Kunstereignisse', Das Kunstwerk, vol.35, June 1982, p.52; Flavio Caroli, 'Pollock et Ie Cubisme' in Jackson Pollock, exh. cat., Musée national d'art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris 1982, p.34,

repr. p.186 (col.); E.A. Carmean Jr, 'Les Peintures noires de Jackson Pollock et Ie projet de l'église de Tony Smith' in

Jackson Pollock, exh. cat., Musée national d'art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris 1982, pp.56 and 72-6, repr. p.186 (col.); E. A. Carmean Jr, 'The Church Project: Pollock's Passion Themes', Art in America, vol.70, Summer 1982, pp.119-21, repr. p.118; Elizabeth Frank, Jackson Pollock, New York 1983, p.95, pl.84; Francis Frascina and Charles Harrison, Abstract Expressionism and Jackson Pollock, Open University, Milton Keynes 1983, p.65, fig. 14 and pl.Xlll.83; Jeffrey Potter, To a Violent Grave: An Oral Biography of Jackson Pollock, New York 1985, p.156; Jeremy Lewison, Jackson Pollock: Three Major Paintings, Tate Gallery, [1988], [pp.6-8] repr. (col.); William Packer, 'Abstract painting is here to stay', Financial Times, 7 April 1988, p.19; Tate Gallery Report 1986-8, 1988, pp.76-7, repr. p.77 (col.). Also repr: Bryan Robertson, Jackson Pollock, New York and London 1960, pl.33; Clement Greenberg, 'After Abstract Expressionism', Art International, vol. 6, Oct. 1962, p.26; Dore Ashton, The Unknown Shore: A View of Contemporary Painting, Boston 1962, p.127; Dore Ashton, 'New York Commentary: Pollock at Marlborough-Gerson', Studio International, vol.177, May 1969, p.245; Hans Namuth, L' Atelier de Jackson Pollock', Paris 1978, pp.82 and 84-5 (details); E.A. Carmean Jr, 'Jackson Pollock: Classic Paintings of 1950' in E. A. Carmean Jr and Eliza E. Robertson (eds.), American Art at Mid-Century. The Subjects of the Artist, exh. cat., National Gallery of Art, Washington 1978" fig.25; Yale University Art Bulletin, vol.38, Winter 1982, p.36

T03978 is one of a series of paintings made in 1951 which are entirely or predominantly black in which Pollock returned to more overt representation and figuration. The subject of the painting has been variously interpreted and there is no general agreement as to exactly what is depicted. Broadly speaking there appear to be at least two and possibly three horizontal forms and possibly two or three vertical forms, all of which may or may not represent human figures. The painting is entirely in black except for splashes of red, green and yellow along the bottom edge of the canvas and a reddish stain towards the centre. It seems unlikely that these were deliberately applied but they appear to have been intentionally retained. A small patch, towards top right, was applied by the artist to cover a tear to the canvas made at the time the painting was executed.

The transition from making coloured paintings to black paintings was effected through drawing. After his successful show at Betty Parsons' Gallery at the end of 1950 Pollock was in a state of depression. In October that year, after finishing outdoor filming with Hans Namuth for the latter's film on Pollock (first shown at the Museum of Modern Art, New York on 14 June 1951) Pollock suddenly resumed drinking, having previously arrested his alcoholism late in 1948. The doctor who had helped him, Dr Edwin Heller, had recently died and his death, the extreme cold outside and the possible strain imposed on Pollock by the invasion of his privacy by a film maker may collectively have caused this resumption. Although Lee Krasner stated that Pollock never drank while he worked (quoted in Francine du Plessix and Cleve Grey, 'Who was Jackson Pollock?', Art in America, vol.55, May-June 1967, p.48) it is believed by some critics, such as O'Connor, that his resumed state of alcohol dependency, itself questioned by E.A. Carmean Jr, had a bearing on the mood of the black paintings of 1951. While this is plausible, it should not be forgotten that Pollock's that black had always been the principal element in Pollock's painting and that, as early as 1948, he had made paintings almost entirely in black: 'Number 7A' 1948, (collection Kimiko and John Powers, repr. O'Connor and Thaw 1978, II, pp.32-3 no.210),and again in 1950 in the large painting 'Number 32' (Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, repr. ibid., pp.98-9 no.274).

In addition to the physical crisis induced by alcoholism Krasner suggested that Pollock faced a crisis in his painting when she stated: 'After the '50 show, what do you do next? He couldn't have gone further doing the same thing' (B.H. Friedman, 'An Interview with Lee Krasner Pollock' in Jackson Pollock: Black and White, exh. cat., Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, New York 1969, p.7). However Pollock perceived his own position, clearly many of his contemporaries felt that he had reached an impasse. Reviewing the 1951 exhibition of black paintings, in which T03978 was exhibited, James Fitzsimmons wrote: 'If would seem that Pollock has confounded those who insisted he was up a blind alley' ('Fifty Seventh Street Review: Jackson Pollock', Art Digest, VoI.26, 15 Dec. 1951, p.19). Howard Devree echoed these sentiments when he stated that Pollock seemed 'to be getting away from what threatened to be a dead end' ('By contemporaries...', New York Times, 2 Dec. 1951, section 2, p.11). It is possible, therefore, that Pollock adopted a new strategy because he felt there was nothing left to explore in the style for which he had become famous in the previous three years. The large dripped paintings had sold reasonably well and, therefore, commercial reasons for the change should be discounted. It is true that Pollock had been heavily criticised for his innovative technique of dripping, particularly outside of the art world, and he was sensitive to such criticism - witness his remarks to Alfonso Ossorio, his neighbour and friend, that the black paintings of 1951 would disturb 'the kids who think it simple to splash a Pollock out' (quoted in O'Connor and Thaw 1979, IV, p.261). Pollock may also have felt a sense of unease at the degree of abstraction which he had achieved in the previous two years. He would have been receptive to Clement Greenberg's disguised warning in 1948 that the 'all-over' picture 'comes very close to decoration – to the kind seen in wallpaper patterns that can be repeated indefinitely' ('The Crisis of the Easel Picture' in Art and Culture, Boston 1965, p.155). Greenberg himself, assessing the change in Pollock's art in 1951, stated retrospectively that Pollock, like the Analytical Cubists, ' 'drew back... when he found himself halfway between easel painting and an uncertain kind of portable mural' ('American Type Painting' in ibid., p.219). Indeed when reviewing Pollock's 1952 exhibition at Betty Parsons' Gallery he revised his earlier contention that Pollock was moving in a direction beyond the easel painting for he stated that Pollock's black paintings 'hint... at the large future still left to easel painting' ('Art Chronicle: Feeling is all', Partisan Review, Jan.-Feb.1952, p.102). Previously he had regarded Dubuffet as the guardian of the easel (mobile) painting, Dubuffet being an artist whom Pollock also admired. It is possible, therefore, that Pollock was sensitive to Greenberg's anxiety about his drip painting becoming decorative and responded to the challenge to extend the life of the 'easel picture'. In this context it should be remembered that Pollock continued to view Picasso as an artist against whom he should measure himself and that Picasso not only drew back from total abstraction, as Greenberg remarked in 1948, but also painted figurative works which continued to have an enormous influence on Pollock. Furthermore, Picasso made a number of paintings which in size and sometimes in technique come close to being 'all over' paintings; for example 'Guernica' 1937 (Museo del Prado, Madrid), 'The Charnel House' 1945 (Museum of Modern Art, New York, repr. William Rubin (ed.), Pablo Picasso: A Retrospective, exh. cat., Museum of Modern Art, New York 1980, p.389) and 'The Kitchen' 1948 Jan Krugier Gallery, Geneva, repr. ibid., p.397) all of which are grisaille paintings. The latter is also a particularly linear painting while 'The Charnel House' displays the overlapping, interlocking ambiguity of form and space found in a painting such as 'Number 14' (see below). It might be speculated, therefore, that the black paintings were Pollock's ultimate challenge to Picasso on the latter's own ground.

One other European artistic influence might have been pertinent to Pollock's painting in 1951. In an undated letter written to Alfonso Ossorio towards the end of January 1951, Pollock asked Ossorio, who was staying in Paris, whether he had seen the Matisse Chapel in Vence (quoted in O'Connor and Thaw, IV, p.257). The Matisse Chapel contains black line drawings on ceramic tiles representing religious themes, among them the Stations of the Cross. In 1951, Pollock was talking with the architect and sculptor Tony Smith about making paintings for a Catholic church on Long Island and, therefore, Matisse's designs would have been of great interest to him (for further discussion of the possible religious connotations of the black paintings see below).

Whatever Pollock's artistic concerns his depression appears to have loomed large in his thoughts. In the letter written to Ossorio (previously cited) Pollock referred to his depression and drinking and stated that New York City, where he was staying, was 'brutal'. In an earlier letter of 6 January he told Ossorio how he found 'New York terribly depressing' (both letters quoted in O'Connor and Thaw 1978, IV, p.257). His dislike of New York may have been partially due to a sense of anticlimax after the opening of his exhibition, the fact that he was away from his home in the country at Springs, and that he had been unsuccessful in his search for mural commissions. Pollock's morose mood may, therefore, have contributed to the exclusion of colour from many of his paintings of 1951, although such a conclusion is speculative.

As reported to Ossorio in a letter of 7 June 1951, Pollock 'had a period of drawing on canvas in black - with some of my old images coming thru' (quoted in O'Connor and Thaw 1978, IV, p.261). He had returned to Springs with his wife by early May. He had made ten black drawings on paper in 1950 (repr. O'Connor and Thaw 1978, III, pp.272-82 nos 787-801) which in some cases anticipate some of the changes in terms of imagery that he was to implement in the paintings of 1951. However, Pollock never completely eliminated the image in his drawings and it is arguable that he never did so over a sustained period of time in his paintings. Therefore special importance should not necessarily be conferred upon these drawings. However, the drawings of 1951, which are more prolific in number, parallel the paintings of the same year in the use of black, the way the paint is allowed to bleed and stain the paper and in their veiled imagery. Pollock made a number of these in New York before beginning the paintings, which he is unlikely to have started before returning to Springs. The drawings of 1950 and 1951 may therefore be seen as transitional, particularly since they are clearly distinguished in their broad handling and lesser dependence on detail from those that precede them chronologically.

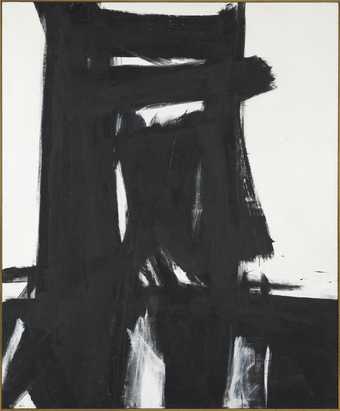

If the almost exclusive use of black can be related to Pollock's change of mood and health and to a desire to move away from the 'blind alley' in which he found himself, there were doubtless other influences acting upon his decision. In March 1950 Samuel Kootz mounted an exhibition in his gallery entitled Black or White: Paintings by European and American Artists which included paintings in black and white by Baziotes, Bultman, de Kooning, Gottlieb, Motherwell, Tobey and Tomlin as well as Miró and Dubuffet, although Dubuffet's painting reportedly was neither black nor white. Pollock saw this show and may have seen the exhibition of black and white paintings by Franz Kline at the Charles Egan Gallery (Oct.-Nov. 1950). It has been suggested by O'Connor that Pollock 'could not have but felt a certain need to outdistance his local colleagues' not by working in black but in 'allowing his "early images" to re-express themselves in a simplification of his pouring technique' (1980, p.5). However, as Lawrence Alloway has pointed out, Pollock's black paintings do not make use of white, unlike those of his contemporaries who, according to Alloway, 'never used black singly' ('Pollock's Black Paintings', Arts Magazine, vol.43, May 1969, p.44). De Kooning had employed black singly in drawings of 1949-50 but so had Pollock. Therefore, while the 'Black or White' exhibition might have stimulated Pollock it is only one of many possible explanations for Pollock's change.

If Pollock made a conscious decision in 1951 it was entirely characteristic that he should begin through drawing. Before each of the stylistic shifts of previous years he had undergone a period of intensive drawing, trying out new ideas and assimilating the experience of other artists' work. The drawings of 1950 and 1951 seem to be closely related to de Kooning's black drawings of 1949-50, although it cannot be stated field categorically that Pollock had seen them. For the most part, however, Pollock's drawings differ markedly from some of the paintings of 1951 in their lack of density and their continued reliance on the arabesque. It might be suggested that those black paintings which are most linear were among the first to be executed, since they are closer to the drawings, and that 'Number 14', being densely painted and less overtly linear, was painted towards the end of the series. A photograph taken by Hans Namuth in Pollock's studio sometime in the latter half of 1951 (repr. O'Connor 1978, fig. 3) shows 'Number 14' in an unfinished state on the same piece of cloth as 'Number 10' (for Lee Krasner's explanation of this see below), which suggests that these two works were made at around the same time or consecutively. Furthermore they might originally have been intended to remain as one image. More crucially, however, the fact that 'Number 14' was unfinished at that moment proves that it was completed after 'Number 22', 'Number 9', 'Black and White Painting II', 'Number 24', 'Number 27', 'Number 6', 'Brown and Silver II', 'Brown and Silver I' and 'Number 8' (all of which are shown in the same photograph) and, therefore, was not early in the series.

The execution of these black paintings, has been described at length by Lee Krasner in an interview with B.H. Friedman:

Jackson used rolls of cotton duck, just as he had intermittently since the early 'forties. All the major black-and-white paintings were on unprimed duck. He would order remnants, bolts of canvas anywhere from five to nine feet high, having maybe fifty or a hundred yards left on them - commercial duck, used for ships and upholstery, from John Boyle down on Duane Street. He'd roll a stretch of this out on the studio floor, maybe twenty feet, so the weight of the canvas would hold it down - it didn’t have to be tacked. Then typically he'd size it with a coat or two of 'Rivit' glue to preserve the canvas and to give it a harder surface. Or sometimes, with the black-and-white paintings, he would size them after they were completed, to seal them. The 'Rivit' came from Behlen and Brother on Christopher Street. Like Boyle’s, it’s not an art-supplier. The paint Jackson used for the black-and-whites was commercial too - mostly black industrial enamel, Duco or Davoe & Reynolds. There was some brown enamel in a couple of the paintings. So his 'palette' was typically a can or two of this enamel, thinned to the point he wanted it, standing on the floor beside the rolled-out canvas. Then using sticks, and hardened or worn-out brushes (which were in effect like sticks), and basting syringes, he’d begin. His control was amazing. Using a stick was difficult enough, but the basting syringe was like a giant fountain pen. With it he had to control the flow of ink as well as his gesture. He used to buy those syringes by the dozen... With the larger black-and-whites he'd either finish one and cut it off the roll of canvas, or cut it off in advance and then work on it. But with the smaller ones he'd often do several large strips of canvas and then cut that strip from the roll to make more working space and to study it. Sometimes he'd ask, 'Should I cut it here? Should this be the bottom?' He'd have long sessions of cutting and editing, some of which I was in on, but the final decisions were always his. Working around the canvas - in 'the arena' as he called it - there really was no absolute top or bottom. And leaving space between paintings, there was no absolute 'frame' the way there is working on a pre-stretched canvas. Those were difficult sessions. His signing the canvasses was even worse. I'd think everything was settled - tops, bottoms, margins - and then he'd have last-minute thoughts and doubts. He hated signing. There's complex is not icon- something so final about a signature... Sometimes, as you know, he'd decide to treat two or more successive panels as one painting, as a diptych, or triptych, or whatever. Portrait and a Dream is a good example. And, do you know, the same dealer who told me Jackson's black-and-whites were accepted, asked him now, two years later, why he didn't cut Portrait and a Dream in half! (Friedman 1969, pp.8 and 10).

Because Pollock applied the paint principally by pouring, O'Connor has called these works 'pourings'. Lawrence Alloway in the article previously cited characterised Pollock's methods as follows:

The paint, though subject to exceptional control, was not applied by touch; the paint impressions that we see were formed by the fall and flow of liquid, in the grip of gravity, onto a surface that was not hard and firm, like a primed canvas, but soft and receptive as sized but unprimed duck. Thus the black, even when applied in a continuous stream, does not produce a strongly directional reading. It burrs at the edges as it leaks out onto the canvas. The effect is somewhat like photographic enlargements of an etched line, in which the irregularities of the edges turn the contours into sensually fraying thresholds. The black line tends to dilate as a mark rather than to converge upon enclosed areas. Thus what looks like drawing is, in fact, a restrained but pervasive way of painting; the black paintings are concerned with the fusion of colour and surface, of paint and field (p.41).

Krasner's and Alloway's descriptions characterise the nature of 'Number 14' and its execution. Pollock used commercial paints because they were more liquid than oil paint and he had used enamel paints in the dripped paintings of the previous three years. As stated above, 'Number 14' is shown still attached to 'Number 10' (repr. O'Connor and Thaw 1978, II, p.141 no.326) which bears out Krasner's statement regarding if or where to cut the canvas. It may even have been in his mind to treat the two works as a diptych as in 'Portrait and a Dream' 1953 (Dallas Museum of Fine Art, repr. O'Connor and Thaw 1978, II, no.368 pp.202-3).

While the method of execution of 'Number 14' is easily identifiable its subject remains enigmatic. O'Connor (1980), in an analysis of all the black paintings, divides the series into six groups characterised as follows: 'The frontal figure' (for example, 'Number 23' 1951, Chrysler Museum of Norfolk, Virginia, repr. O'Connor and Thaw 1978, II, p.153 no.335); 'the seated figure', for example 'Number 21' 1951, (formerly Lee Krasner, repr. O'Connor and Thaw 1978, II, p.152 no.334); 'the figure joined to the complex' where the complex is not iconographically legible (for example, 'Echo: Number 25' 1951, Museum of Modem Art, New York, repr. O'Connor and Thaw 1978, II, p.167 no.345); 'the figure free of the complex' (for example, 'Number 7', Reginald and Charlotte Isaacs, Cambridge, Massachusetts repr. O'Connor and Thaw 1978, II, p.139 no.324); 'the figure alone' (for example Number 7' 1952, formerly collection of Lee Krasner, repr. O'Connor and Thaw 1978, II, p.176 no.354) and 'the recumbent figure' of which 'Number 14' is a prime example. This last group O'Connor characterises as 'a group of horizontal works which contain, as in the second and third groups, a head or sitting figure to the left and what might be loosely construed as a recumbent figure across the centre and right of the picture area' (p.22). As with the works in the other groups, and in common with other historians and critics, he sees stylistic precedents for this last group in Pollock's earlier paintings of the pre-1947 period. Writing about the last group of works from psychological point of view O'Connor states that

they are best understood not in terms of explicit sexual congress... but in terms of the figure/protagonist/artist's struggle in these works of 1951 to re-establish his sense of, and capacity for, relationship. The over-riding drama of all these dark paintings is the eternal struggle to break away from the strange hold of the mother complex and to assert, first independence, and then willingness to risk freely and knowingly, love (p.25).

O'Connor relates Pollock's use of black paint to what he terms his 'birth trauma: ...choked by the cord, and, according to his mother, "born as black as a stove"'. Thus Pollock's mature method of pouring out line after line of paint through the air to the canvas surface can be seen, on at least one level of determination, as a continuous symbolic attempt to throw off the maternal stranglehold' (p.9). He also regards black as symbolic of Pollock's mourning for the loss of sobriety and notes that in March 1951 he made his Will. 'To make a will is, in a sense, to mourn oneself’ (p.4). All such interpretations remain speculative. Pollock did not identify the subjects of his paintings and there is a little material available from which to draw conclusions.

E. A. Carmean Jr. relates the black paintings to an abortive project to build a Catholic church on Long Island designed by Tony Smith. The project was conceived in 1950 and Smith approached Pollock to make ceiling paintings in the manner of the drip paintings of 1950. However, Smith was impressed by Namuth's film of Pollock painting on glass and according to Carmean, asked Pollock to make painted windows for the church. Carmean states that Pollock was aware that, when silhouetted against the sky, all colour becomes black and that accordingly he began to paint only in black. He concludes that figurative motifs would have been appropriate for a Catholic church and that some of the black paintings were studies for windows. In his detailed analysis of 'Number 14' he considers that it represents a Deposition or Lamentation based on Picasso's 'Crucifixion 1930' (repr. [Alexandre Lieven), The Musée Picasso, Paris, 1986, p.74 in col.) with the vertical form of St. Mary Magdalen on the right, St. John on the left and the horizontal forms in the centre which depict Christ and the robbers. Rosalind Krauss has argued that Pollock's decision to make black paintings predates the showing of Namuth's film since he wrote to inform Ossorio of his black works on 7 June 1951, the week before the showing of the film. Furthermore, the black paintings are not modular, which they would have to be if they were designs for regular sized windows, and Pollock had always been interested in subject matter. On the Picasso as a specific source, she claims that it is unlikely that Pollock could or would have copied the 'Crucifixion' so closely with the poured method and that he could only have seen the work in reproduction. Furthermore, Pollock tended to place emphasis on the unconscious as opposed to what he called 'illustration'.

Frascina and Harrison, in summarising the views of Carmean and O'Connor state that 'both are more or less daft:

Each author thinks he has found an 'external' causal explanation for Pollock's dramatic return to figuration, and has pursued it to absurdity, in the process pinning down the painting's elusive expressive quality with the little tacks of his own anxiety to control it. Perhaps - if we can accept the genetic persistence of a 'life of themes and subjects' in Pollock's work of 1947-50 - we are left with no real drama to explain in Pollock's change of style. It does not seem necessary either to dig up some external cause (the church project), or to posit a Pollock in some persisting state of crisis, to explain the paintings.

Frascina and Harrison characterise the 1947-50 drip paintings as transitional works

in which Pollock invented, practices and gained fluency in a highly individual technique - a technique through which he had acquired sufficient skill and confidence by 1950 to give the private, ‘unconscious’ imagery supposedly generated in automatic drawing, the vividness, scale and grandeur of a public art, an art both expressive and monumental, a kind of easel painting which aspired to the presence of mural (pp. 65-6).

While there may be some truth in this, the implication that Pollock was following a programme of loosening up his paint application, in the knowledge that he would return to the 'unconscious images' of his earlier paintings at a later date, is unsubstantiated.

All that is known for certain in regard to the black paintings is that Pollock was interested in mural painting (the tradition of which involved the depiction of subjects); he was in discussion with Tony Smith about making windows for the projected Catholic church; he wished to explore painting on glass as he stated in his interview with William Wright (quoted in O'Connor and Thaw 1978, IV, p.251); and that 'he was tending more and more to religion' (Lee Krasner in du Plessix and Grey 1967, p.50). None of this proves the theories of O'Connor, Carmean or any other commentators. Indeed, if Krasner is correct in suggesting that Pollock only decided on the orientation of his paintings at the time of signing them, then Carmean's interpretation can be discarded.

This being the case, then an examination of 'Number 14' as a portrait format work produces interesting results. By rotating the picture ninety degrees anti-clockwise it becomes immediately apparent that the two horizontal shapes which were at the bottom of the painting now become totemic figures, similar to those in 'Two' c.1945 (Peggy Guggenheim Foundation, Venice, repr. O'Connor and Thaw 1978, I, p.121 no.123). If the two white horizontal forms are totems, possibly painted as vertical figures but reorientated at the last moment, it is also possible to read a sphinx-like figure on the left with legs, shortened body and head, facing nose to nose, a second figure of which it is possible only to make out a head (all this when the painting is displayed the correct way). However, a drawing in Pollock's last sketchbook (repr. Jackson Pollock: The Last Sketchbook, New York both positive 1982, [p.26]) depicts an animal, reminiscent of cave drawings, which seems closely related to the upper horizontal figure in 'Number 14'. Clearly 'Number 14' is open to many possible interpretations, none of which can be categorically correct.

In terms of format 'Number 14' is reminiscent of "The Guardians of the Secret' 1943 (San Francisco Museum of Art, repr. O'Connor and Thaw 1978, I, p.91 no.99) in its use of a horizontal image flanked by two verticals, and also 'Pasiphäe' c.1943 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, repr. O'Connor and Thaw 1978, I, p.93 no.101) and is closely related to 'Number 11' 1951 (repr. O'Connor and Thaw 1978, II, pp.160-1 no.341).

The black paintings constitute the last major group of works made by Pollock before his death in 1956. As such they invite comparison with Goya's late series of black paintings (Museo del Prado, Madrid). Ossorio stated that he gave Pollock 'a facsimile edition of Goya's Disasters and Capriccios and reproductions of the black paintings from Goya's house; he was very enthusiastic about these' (du Plessix and Grey 1967, p.58). In a letter to the compiler (13 May 1988) Ossorio relates that he made the gift in 1949. Although Goya should not be seen as a specific source for the black paintings, both series share an interest in surreality and demonic figures.

'Number 14' is generally considered to be one of the finest of the black series. Reviewing Pollock's exhibition at the beginning of 1952, Greenberg wrote that 'his most recent show... reveals a turn but not a sharp change of direction; there is a kind of relaxation, but the outcome is a newer and loftier triumph' ('Art Chronicle: Feeling is All', Partisan Review, Jan.-Feb. 1952, p.102). Greenberg believed that this exhibition confirmed that 'Pollock is in a class by himself’:

others may have greater gifts and maintain a more even level of success, but no one in this period realises as much and as strongly and as truly. He does not give us samples of miraculous handwriting, he gives us achieved and monumental works of art, beyond accomplishedness, facility or taste. Pictures 'Fourteen' and 'Twenty-Five' in the recent show represent high classical art: not only the identification of form and feeling, but the acceptance and exploitation of the very circumstances of the medium of painting that limit such identification (ibid.).

'Echo: Number 25' (Museum of Modern Art, New York, repr. O'Connor and Thaw 1978, II, p.167 no.345) is more linear and open than 'Number 14' and demonstrates the extent to which drawing continued to play an important part in Pollock's painting. However, unlike in the works of 1939-41, where contour describes volume, contour in the black paintings is truly integrated into the field by the staining and bleeding of the paint. It becomes both positive and negative, as is the case in 'Number 14' where unpainted canvas has as much weight as the dark, painted areas. Bernice Rose has written:

The mark, the paint that thins and thickens, may simply be line; or it may describe contour; or it may be positive or negative, form or shadow, and here Pollock realises the possibilities of black as colour. This is a new kind of figurative drawing, one in which figuration is integrated into the allover field through a subtle balancing of descriptive and non-descriptive, of 'contour' and calligraphy, so that the notion of form in volumetric space is eradicated (Jackson Pollock: Drawing into Painting, exh. cat., Museum of Modern Art, New York 1980, p.20).

While Rose's description may be true for a number of the black paintings it is not wholly true of 'Number 14', where space is not eradicated but ambiguous. Space in 'Number 14' is both positive and negative, and it is this ambivalence, rooted in Analytical Cubism, which makes it so difficult to read.

Published in:

The Tate Gallery 1984-86: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions Including Supplement to Catalogue of Acquisitions 1984-86, Tate Gallery, London 1988, pp.238-245, reproduced p.238

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- figure(2,270)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- gestural(763)

- education, science and learning(1,416)

-

- psychology, Jung(29)