- Artist

- Pablo Picasso 1881–1973

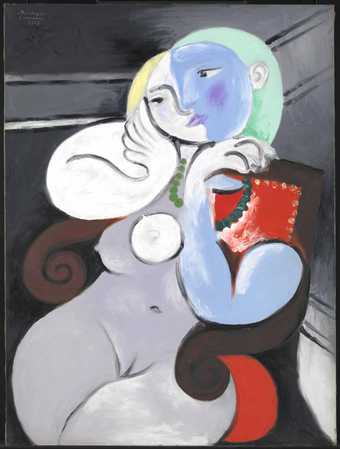

- Original title

- Buste de femme

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 727 × 600 mm

frame: 911 × 799 × 81 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1949

- Reference

- N05915

Summary

Bust of a Woman is an oil painting on canvas by Pablo Picasso. The portrait is small in size with a dark palette dominated by brown, blue, grey and yellow ochre tones. It features a female nude presented in half-length format. Her body is angled away from the viewer, turned slightly to her right. She looks down and her shoulders appear slumped. Her upper body is rendered in Picasso’s proto-cubist style, in which her breasts, shoulders and head appear to fracture into discreet objects with almost geometric edges. She is set against a grey and brown background. The shifting directions of the brushstrokes indicate the depth of the surfaces and enhance the model’s facial features such as the conical socket of the left eye. Just as the painting does not offer a superficial likeness, so the sitter remains anonymous in the title of the work. Picasso has signed the painting in the bottom right corner.

Picasso produced Bust of a Woman in 1909, although it is unclear at what point in the year. According to Tate curator Roger Alley, writing in 1981, sometime in the spring is most likely, which would mean Picasso painted the portrait in his studio on the Boulevard de Clichy, Paris (Alley 1981, p.594). However, summer 1909 has also been suggested, in which case Picasso was in Horta de Ebro in Spain (Alley 1981, p.594). Art historian Christopher Riopelle has noted that from 1906 onwards Picasso ‘set about fashioning a self-consciously brusque and unresolved manner of handling paint’ (Riopelle, ‘Something Else Entirely: Picasso and Cubism 1906–1922’, in Cowling, Galassi, Robbins and others 2009, pp.55–67, p.56). This rough finish can be seen in Bust of a Woman with brushstrokes not only left visible (for example on the left shoulder), but forming part of the modelling of shape and depth of space in the image.

As one of Picasso’s proto-cubist works, Bust of a Woman contains the angular stylisation of the model’s features from the artist’s analytical cubist period (which developed in 1908–12) but retains a strong element of figuration. Picasso began to experiment outside the conventions of representation in 1906, particularly by looking beyond the western tradition. As Riopelle explains, ‘he would bring to bear a range of aesthetic allusions far outside the Western canon’ (Riopelle 2009, p.56). One of the sources to which Picasso turned was African and Polynesian sculpture and arguably this visual language had an impact on Bust of a Woman. Alley references a 1976 letter of William Fagg (Keeper of the Department of Anthropology at the British Museum 1969–74), in which Fagg observes that Bust of a Woman ‘looks very much as if it were derived from one or more African pieces, but as usual with works by artists of the School of Paris its source is not easily recognisable’ (Alley 1981, p.594). Fagg may be writing with particular reference to the mask-like representation of the sitter’s features or the sculptural quality achieved through the opaque rendering of the body. Riopelle has argued, however, that despite stepping outside European painting for inspiration, Picasso continued to work in genres that resided firmly within the western canon, such as still life, portraiture and the nude (Riopelle 2009, p.57).

The model in Bust of a Woman is likely to be Fernande Olivier, Picasso’s partner at the time. As curator Jeffrey Weiss has noted: ‘in 1909 Picasso created a group of works devoted to a single subject, that of his companion Fernande Olivier … The obvious paintings, those in which the subject is clearly Fernande, number close to one dozen’ (Jeffrey Weiss, ‘Fleeting and Fixed: Picasso’s Fernandes’, in Weiss, Fletcher and Tuma 2003, pp.1–50, p.4). Weiss does not identify Bust of a Woman as featuring Olivier, but notes that images of her from this time show her hair in a distinctive ‘coil and a topknot’ and with a prominent jaw (see, for instance, Portrait of Fernande 1909, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein–Westfalen, Düsseldorf) – both elements that are also clearly visible in this portrait (Weiss 2003, p.6). Additionally, the model’s noticeably downturned head in this work is a feature specific to the Olivier portraits (Weiss 2003, p.6).The association of Bust of a Woman with this series of work was explored in the exhibition Picasso: The Cubist Portraits of Fernande Olivier in 2003 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC (see Weiss, Fletcher and Tuma 2003).

More generally, Bust of a Woman sits on a precipice in Picasso’s oeuvre between his working through of lessons about visual perception and his move into analytical cubism. Seated Nude 1909–10 (Tate N05904) is an example of an analytical piece from the following year. Bust of a Woman also belongs to the first set of images the artist dedicated to a single subject, and Weiss observes that ‘such intense devotion to repeated representations of a single “portrait” subject is rare in his oeuvre and does not exist prior to 1909’ (Weiss 2003, p.5). As such Weiss argues that these early works initiated Picasso’s longer-term practice of working in series.

Further reading

Ronald Alley, Catalogue of the Tate Gallery’s Collection of Modern Art other than Works by British Artists, London 1981, reproduced p.594.

Jeffrey Weiss, Valerie J. Fletcher and Kathryn A. Tuma (eds.), Picasso: The Cubist Portraits of Fernande Olivier, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC 2003, reproduced p.52.

Elizabeth Cowling, Susan Galassi, Anne Robbins and others, Picasso: Challenging the Past, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery, London 2009.

Jo Kear

March 2016

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

The treatment of the human figure in the Cubist paintings of Picasso and Braque is often reminiscent of sculpture. In this work, made in mid-1909, Picasso used planes of warm greys and burnt sienna to establish the bulk of the body. The shifting directions of the brushstrokes indicate the depth of the surfaces and enhance individual features such as the conical socket of the eye. Such techniques were inspired by African sculptures. The poet André Salmon described Picasso’s studio as filled with the ‘strange wooden grimaces... [of] a superb selection of African and Polynesian sculpture’.

Gallery label, July 2013

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Film and audio

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- figure(2,270)

- female(1,681)