- Artist

- Francis Picabia 1879–1953

- Original title

- La Feuille de vigne

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 2000 × 1600 mm

frame (without perspex box): 2062 × 1663 × 70 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1984

- Reference

- T03845

Display caption

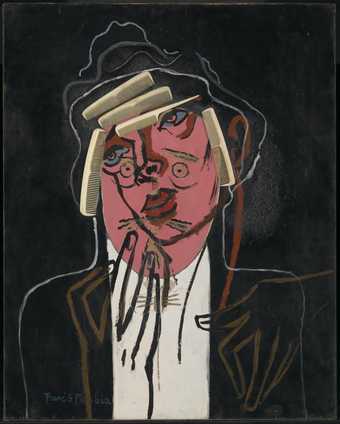

Picabia painted The Fig-Leaf using glossy household paint over another work entitled Hot Eyes. The original painting, which was based on a technical drawing of a turbine brake, caused a scandal when submitted for an important Paris exhibition in 1921. The figure in the new image is derived from Oedipus and the Sphinx (1808), a neo-classical painting by Ingres, with Picabia’s addition of a fig-leaf (the French say ‘vine leaf’) as a reference to censorship. The inscription DESSIN FRANÇAIS (‘French drawing’) sarcastically mocked the contemporary revival of interest in traditional art skills.

Gallery label, July 2008

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Francis Picabia 1879-1953

T03845 The Fig-Leaf

1922

Enamel paint on canvas 2000 x 1600 (78 3/4 x 63)

Inscribed ‘FRANCIS PICABIA' bottom centre, ‘LA | FEUILLE | DE | VIGNE' t.l. and ‘DESSIN FRANÇAIS' lower centre

Purchased from Mary Boone Gallery, New York and Michael Werner, Galerie Cologne (Grant-in-Aid) 1984

Prov: M. Van Heeckeren by 1946 when mentioned in Paris exh. cat. (see Exh.); ...; Mme H. Saint-Maurice, Paris by 1979 when mentioned by William Camfield p.289 (see Lit.); ...; Mary Boone Gallery, New York and Gallerie Michael Werner, Cologne by 1983 when mentioned in Düsseldorf exh. cat. (see Exh.)

Exh: Exposition de 1922, Société du Salon d'Automne, Grand Palais, Paris 1922, (1896, as ‘La Feuille de vigne'); Galerie Colette Allendy, Paris, Oct.-Nov. 1946 (17); Francis Picabia, Galeries nationales au Grand Palais, Paris, Jan.-March 1976 (122, repr. p.103, as ‘La feuille de vigne'); Francis Picabia, Städtische Kunsthalle, Düsseldorf, Oct.-Dec. 1983, Kunsthaus Zurich, Feb.-March 1984, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, April-May 1984 (46, repr. p.65, as ‘La feuille de vigne [Das Feigenblatt]')

Lit: Francis Picabia, exh. cat., Galeries nationales au Grand Palais, Paris 1976, p.97 and p.103, repr., as ‘La feuille de vigne'; William Camfield, Francis Picabia: His Art, Life and Times, Princeton 1979, pp.188-9, fig. 209, as ‘La Feuille de vigne (Fig-Leaf)'; Francis Picabia, exh. cat., Städtische Kunsthalle, Düsseldorf 1983, p.175, repr. p.65, as ‘La feuille de vigne (Das Feigenblatt)'; Maria Llusa Borràs, Picabia, 1985, pp.235-6 and p.460, fig. 457 (col.); Tate Gallery Report 1984-6, 1986, p.74, repr. in col., as ‘The Vine Leaf'

When acquired by the Tate Gallery T03845 was known as ‘The Vine Leaf'. In the context of art, however, the accepted translation of the phrase ‘feuille de vigne' is ‘fig-leaf', in the sense of a cache-sexe, and the painting has been retitled accordingly. Although the leaf shown in the painting resembles in fact a vine leaf and not a fig-leaf, this interpretation of its French title is supported by the circumstances surrounding the making of the work.

Picabia painted T03845 in the early months of 1922 whilst living at Tremblay-sur-Mauldre. In a letter dated the beginning of May of that year André Breton, the leading figure within the French Dada group, asked Picabia's permission to reproduce ‘The Fig-Leaf' in the magazine Littérature. It is not known whether or not Picabia assented to this and, in fact, the painting was not reproduced in the magazine. Breton's letter, however, indicates that the painting was completed by the late spring of that year (Michel Sanouillet, Dada à Paris, Paris 1965, p.521).

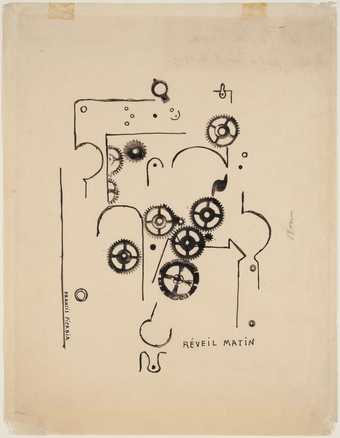

As can be seen from the uneven surface of the canvas, ‘The Fig-Leaf' was painted over an earlier work. This was ‘Hot Eyes', a painting which had caused a scandal when exhibited in the Salon d'Automne of 1921 (repr. Paris exh. cat. 1976, p.97, as ‘Les yeux chauds'). Inscribed with the ingratiating phrases ‘REMERCIEMENTS | AU SALON D'AUTOMNE' [‘THANKS TO THE SALON D'AUTOMNE'] and, referring to the President of the Salon, ‘HOMMAGE | A | FRANTZ JOURDAIN' [‘HOMAGE TO FRANTZ JOURDAIN'], the earlier painting provocatively drew attention to the role of particular individuals and institutions in arranging the public display of new art. Before the Salon opened a rumour circulated to the effect that Picabia intended to hang an ‘explosive' picture. This obliged Frantz Jourdain to issue a press statement reassuring visitors that their safety was not in jeopardy as all the exhibits had been checked. The succès de scandale

was completed when Le Matin

reproduced side by side a sketch of ‘Les Yeux chauds' and a diagram of the mechanism of an air-turbine brake which had been published in a scientific journal in 1920. The comparison demonstrated that the arrangement of lines and circles in Picabia's painting had been copied from this source (‘La Turbine et le Dada', Le Matin, 9 Nov. 1921, p.2, reprinted in Paris exh. cat. 1976, p.96). Picabia responded to this article by saying that his copying of this diagram was no different from Cézanne's copying of apples and he added that he saw no reason why his painting, hitherto deemed ‘inadmissable' and incomprehensible, should suddenly be thought to be understandable by all simply because it was now known to use a certain ‘convention of representation' (‘L'Oeil cacodylate', Comoedia, 23 Nov. 1921, p.2, reprinted in Paris exh. cat. 1976, p.96).

Picabia's relations with the official Salons hit a new low when two of his three submissions to the Salon des Indépendants were refused in January 1922. From the reply that Picabia sent to Paul Signac, the President of the Société des Indépendants, it appears that among the reasons given for this refusal were that Picabia had simply been seeking publicity in submitting these provocative works and that, being well-off, he did not need to exhibit anyway. In his letter Picabia pointed out that this exclusion by a jury-less Salon was unprecedented for non-obscene works. During the exhibition he had supporters distribute a tract he penned complaining of the increased conservatism of all of the Salons and advising members of the public where the excluded works could be seen (text reprinted in Paris exh. cat. 1976, p.120).

In painting ‘The Fig-Leaf' over the earlier notorious work and submitting it in this new form to the Salon d'Automne in 1922 Picabia was seeking to renew the polemic concerning the status of his works as art and his right as an artist to have them exhibited in the principal exhibition venues. In overpainting the first work with a plainly figurative, and hence in a certain sense acceptable, image, Picabia could be seen as drawing attention to what he saw as the censorship, symbolised in the image by the fig-leaf over the figure's genitals, operative in the exhibiting and marketing of art.

The ‘correctly' drawn silhouetted figure and the inscription ‘DESSIN FRANCAIS' [‘French Drawing'] found in T03845 allude not only to the conservatism of art institutions but also to the contemporary revival of interest in the traditions of French art which had been greatly spurred by the re-opening in 1920 of the galleries in the Louvre in which the French collection was hung. With the rather curious pose of the silhouetted figure in ‘The Fig-Leaf', Picabia appears to have alluded to one of the celebrated masterpieces in the Louvre collection, ‘Oedipus and the Sphinx', by Ingres, a key figure in the neo-classical movement of the early nineteenth century and champion of the relative importance of line over colour in painting. Executed in 1808, this painting shows from a side view the almost naked figure of Oedipus who, leaning forward to reply to the riddles posed by the Sphinx, supports his left elbow on his bent left leg which is resting on a boulder. The pose of Oedipus is closely echoed in that of the figure in T03845. The position of the lower foot of Picabia's figure, however, indicates that, in contrast to the Ingres painting, it is the figure's right leg that is bent and therefore the genitals would be visible were it not for the fig-leaf. With this small reversal of the positioning of the figure's legs Picabia made overt what was otherwise the disguised censorship or prudery involved in the careful positioning of limbs and drapery in traditional academic art.

The re-opening of the Louvre, and the major and well-publicised retrospective of Ingres' work at the Hôtel des commissaires-priseurs in Paris in May 1921, made Picabia's allusions to ‘Oedipus and the Sphinx' topical. There is, however, no need to assume that he had actually seen the Ingres painting. In his series of paintings known as ‘transparencies' of 1928-32 in which he borrowed imagery from past masters such as Botticelli, Dürer and Titian, Picabia relied on second-hand sources of published illustrations. Maria Lluisa Borràs writes that Picabia never worked from the originals in museums but used commonly available prints and book illustrations as his sources. In this context she quotes Picabia's son, Lorenz Everling, as saying that his father had a trunk full of art books in his studio (Borràs 1985, p.340). The allusion to the pose of the Ingres painting in T03845 is one of the earliest examples of the direct quotation from the great masterpieces of the past that was to form a major theme in Picabia's work. Whilst later works such as the ‘transparencies' show a subversive engagement with the traditions of art, the reference to Ingres in ‘The Fig-Leaf' should be seen primarily as an ironic comment by the artist on the ‘return to order' movement in contemporary art. In 1923 Picabia complained that there was no longer any distinction between old-fashioned and so-called avant garde artists, between painters such as Cormon (an academic artist with whom he had studied for approximately six years at the turn of the century) and Picasso. ‘Practically no-one knows what to do any more', he claimed, ‘and so they shout ‘Long live classicism' (‘Le Salon des Indépendants', La Vie Moderne, 11 Feb. 1923, p.1, reprinted in Paris exh. cat. 1976, pp.112-13).

Alongside this work Picabia exhibited in the same Salon ‘Spanish Night' (Ludwig Museum, Cologne, repr. Düsseldorf exh. cat. 1983, p.10 in col., as ‘La Nuit espagnole'), a painting which also combines figures and geometric shapes. Painted in the same black and white enamel paint, this second, slightly smaller work shows the silhouettes of a male figure in the pose of Spanish flamenco dancer and of a naked woman. In the place of the breast and sex of the female figure are concentric, target-like circles, and both figures appear randomly marked by bullet-like holes. Picabia had long employed mysterious or seemingly abstract circular shapes in his paintings. Hovering in the borderline area between figuration and abstraction, these circles can be interpreted either as simple geometric shapes or as schematic representations of, for example, parts of machinery, the courses of heavenly bodies or eyes (Picabia had suffered from an eye disease in previous years). In the summer of 1922 Picabia made a number of watercolours and drawings dominated by circular motifs of the sort found in both ‘The Fig-Leaf' and ‘Spanish Night'.

In the Salon d'Automne of 1923 Picabia exhibited ‘Animal Tamer' (collection Cavalero, repr. Düsseldorf exh. cat. 1983, p.11 in col., as ‘Dresseur d'animaux') which showed a black silhouetted figure with the same elongated nose and upper lip as that of the man depicted in ‘The Fig Leaf'. The source of this image of a masked man has not been identified. However, it suggests reference to the half-masks worn by actors in the Commedia dell'Arte, the sixteenth and seventeenth century form of popular theatre and which in the post-War years enjoyed a revival as part of the modern movement against naturalism in the theatre and which was particularly admired within avant garde circles in Paris. Gino Severini, an Italian artist who lived mainly in Paris in the 1920s, for example, made overt reference to the Commedia dell'Arte in a series of paintings from c.1922 which depict figures wearing black half-masks. Adopting a figurative imagery after his earlier cubist and futurist styles of painting, Severini saw in his masked actors of the Commedia dell'Arte not only a valued link with tradition but also symbols of the condition of man. The Parisian dealer Léonce Rosenberg was a key figure in promoting Severini's new interest in the theme of what was known in France as the ‘comédie italienne'. In 1921 he arranged the commission for Severini to paint murals of scenes of masked actors and harlequins in Sir George Sitwell's Castello di Montegufoni near Florence. Rosenberg himself owned major paintings on this theme including ‘The Two Pulchinellas', 1922 (Musée Municipal de la Haye, repr. Gino Severini, exh. cat., Musée national d'art moderne, Paris 1967, p.24).

It is possible that in depicting a masked figure Picabia was responding to contemporary interest in the harlequinade. With its impromptu and often satirical plays about human weaknesses, the Commedia dell'Arte might have appealed to the Dada artist who was always conscious of ‘acting' before an audience of an exhibition-going public. At the same time, the half-mask can be interpreted as a symbol of pretence and deception, born of a tradition in theatre as outdated as that of the fig-leaf in art. In this light the mask can be seen as a critical allusion to the post-war conservatism of taste and revival of interest in the classical tradition in art which is the central theme of T03845.

If Picabia hoped to arouse a storm of controversy with his two submissions to the Salon d'Automne, he would have been disappointed. Mindful of past adverse publicity, the Committee of the Salon hung Picabia's works in what the critic Maurice Raynal described as the highest, dirtiest, most obscure vault of the hallway (‘Au Salon d'Automne', L'Intransigeant, 31 Oct. 1922, p.2, quoted in Camfield 1979, p.196). William Camfield adds that ‘most of the critics who bothered to consider Picabia's paintings wrote not in outrage but with the unruffled disdain of Marcel Hiver, who described Crotti and Picabia as "old clowns" who "no longer amuse anyone"' (‘La Peinture', Montparnasse, Nov. 1922, p.3, quoted in ibid., p.196).

Published in:

The Tate Gallery 1984-86: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions Including Supplement to Catalogue of Acquisitions 1982-84, Tate Gallery, London 1988, pp.227-30

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- silhouette(388)

- universal concepts(6,387)

-

- irony(304)

- music and entertainment(2,331)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- mask(172)

- ball(50)

- male(959)

- inscriptions(6,664)

-

- French text(139)

- title of work(308)