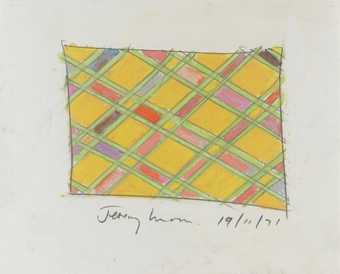

- Artist

- Cornelia Parker CBE RA born 1956

- Medium

- Ferric oxide on paper

- Dimensions

- Support: 560 × 560 mm

frame: 630 × 630 × 41 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1997

- Reference

- T07327

Summary

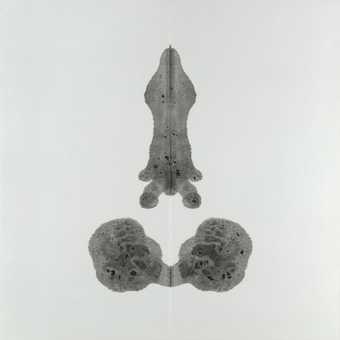

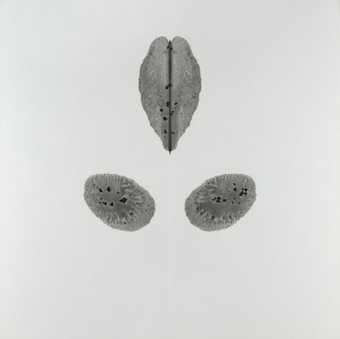

Pornographic Drawing 1996 is a medium-size square work on paper by the British artist Cornelia Parker. In the middle of the otherwise blank composition are two symmetrical abstract shapes, one positioned above the other, that are divided down their centre by a fold in the sheet of paper. The uppermost shape is the largest and consists of a long, vertically oriented column-like form with two oval-shaped protrusions emerging from its sides and two smaller elongated parts extending from its lower end. Below this sits a small, broadly egg-shaped form with a thick black line down its centre. The two delicate shapes are formed from ink that was made using the iron-based material ferric oxide, giving them a variegated tone and texture consisting of thin washes of light and darker grey and thick blobs of black.

This work was made by Parker in 1996, when the artist was living and working in London. It is one of the first produced as part of a series entitled Pornographic Drawings 1995–2006 (see also Tate T07324, Tate T07325 and Tate T07326) that each present a symmetrical and organic composition in tones of grey and black. To make these works, Parker acquired pornographic videotapes that had been confiscated and shredded by Her Majesty’s Customs and Excise in Cardiff, Wales, and extracted the ferric oxide component from the film, suspending it in a solvent to form a liquid and applying it to sheets of white wove paper. She then folded each piece of paper down its centre so that the ferric oxide ink printed itself on both sides, creating a mirror image, after which she unfolded and flattened out the paper. This drawing is presented in a glazed frame and can be shown either individually or in pairs or groups with others from the series.

Parker has made several works that involve items confiscated by Customs and Excise (see, for instance, Exhaled Cocaine 1996), stating in 2013 that she is interested in the way in which such authorities ‘block objects on behalf of society, denying access to what we can import, own, inhale, imbibe or indeed look at’ (Parker in Blazwick 2013, p.100). She originally conceived of re-editing the cut-up pornographic videotapes into a film, but instead chose to use them to make Rorschach drawings – abstract symmetrical ink blots that are presented to patients undergoing psychoanalysis for interpretation as a means of revealing their subconscious thoughts and desires. In 2013 Parker spoke of the chance connection between the erotic nature of the original videotapes and the sexual, although abstract, forms seen in the drawings:

In psychology, Rorschach blots are used to reveal information about the personality of a person through their interpretation of abstract shapes. Somehow, my blots turned out to be particularly explicit, betraying their figurative origins.

(Parker in Blazwick 2013, p.100.)

The title of Parker’s series leads the viewer to compare the blots with male and female reproductive organs such as the penis, vagina, testes and ovaries. However, describing these works on the occasion of their first exhibition in the show Avoided Object at Chapter in Cardiff in 1996, Parker emphasised that they remain open to many different interpretations:

I didn’t dictate what images appeared. I selected the particular set to be in the show because I felt that they worked as ‘pornographic drawings’, but of course they’re very innocent. A child could look at them and see something quite benign. Somebody saw them before they were installed, he didn’t know what they were and said ‘Oh God, they’re disgusting!’. He thought somebody had pressed their body against the paper and that they were body prints.

(Parker in Chapter 1996, pp.60–1.)

Parker has further described the act itself of making these drawings as an expression of her own subconscious, as well as a means of producing a form of abstract art: ‘I’m making you look at them again but they’ve become an abstraction, an abstraction caused by my subconscious because I just dropped these blots of “ink” onto paper and folded it.’ (Parker in Chapter 1996, pp.60–1.) Discussing Parker’s practice in general, curator Iwona Blazwick has suggested that in her repurposing of found materials in ways that reflect on an object’s former purpose and meaning, Parker’s work offers a new definition of abstraction, one that involves ‘the use of something that already exists in the world (not its representation) and the substitution of its original nature or function with another, contrasting and even absurd mode of being’ (Blazwick 2013, p.108).

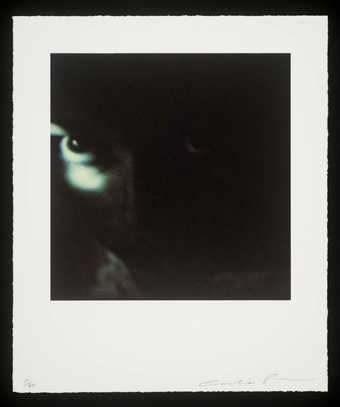

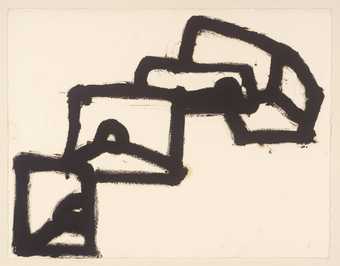

Parker’s engagement with the Rorschach blot has also taken sculptural form in Rorschach 2005, a series of nine sculptures consisting of silver plated objects squashed and suspended symmetrically from the ceiling. She has further explored psychoanalytic practice and its connection to abstraction in works such as Marks Made by Freud, Subconsciously 2000, a macro-photograph of the worn leather of the chair belonging to the founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud, of which Parker stated in 2013: ‘In a way, the creases record a little of his own depths’ (Parker in Blazwick 2013, p.155).

Further reading

Cornelia Parker: Avoided Object, exhibition catalogue, Chapter, Cardiff 1996, pp.60–1, reproduced p.62.

Iwona Blazwick, Cornelia Parker, London 2013, p.100, reproduced p.100.

Mick Maslen and Jack Southern, Drawing Projects: An Exploration of the Language of Drawing, London 2014, p.54.

Celia White

July 2015

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

These delicate, watery images are distinctly sexual in appearance, though the shapes occurred by chance. Although body parts are suggestive, the title actually derives from the medium with which the works have been made. Describing the process, Parker says: ‘I dissolved pornographic video tapes in solvent and made Rorschach blots with the stain. The video tapes were shredded by the Customs and Excise who decide what should be taken out of circulation. I’m making you look at them again but they’ve become an abstraction...I just dropped these blots of “ink” onto paper and folded it. I didn’t dictate what images appeared.’

Gallery label, September 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- figure(2,270)

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- irregular forms(2,007)

- body(4,878)

-

- sexual organs(178)