- Artist

- Sir Eduardo Paolozzi 1924–2005

- Part of

- Ten Collages from BUNK

- Medium

- Printed papers on card

- Dimensions

- Support: 356 × 264 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the artist 1971

- Reference

- T01466

Catalogue entry

Eduardo Paolozzi 1924-2005

T01458–T01467 Ten Collages from ‘BUNK’ Presented by the artist 1971.

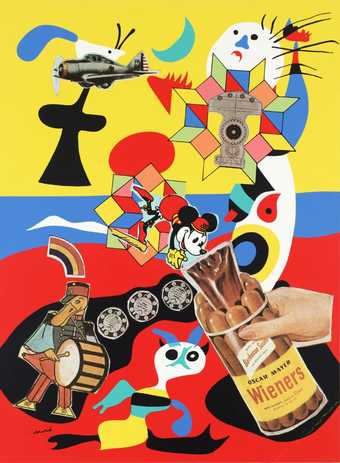

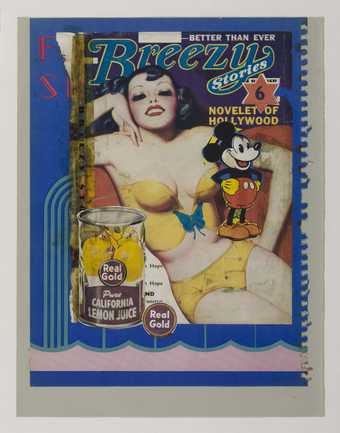

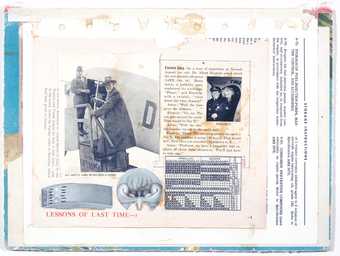

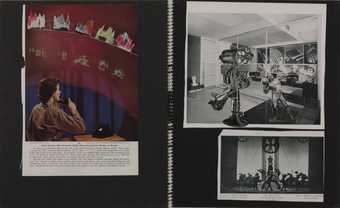

T01466 Sack-o-sauce 1950

Not inscribed.

Collage, 14¼ x 9¾ (36 x 25), mounted on card, 16¿ x 13¿ (43 x 35).

Exh: Tate Gallery, September–October 1971 (27, repr.; listed in catalogue as the silkscreen and lithographic versions, but actually the originals).

Lit: Frank Whitford, catalogue of Tate Gallery retrospective, September–October 1971; Frank Whitford, introductory essay published with the ‘Bunk’ suite of prints, 1972.

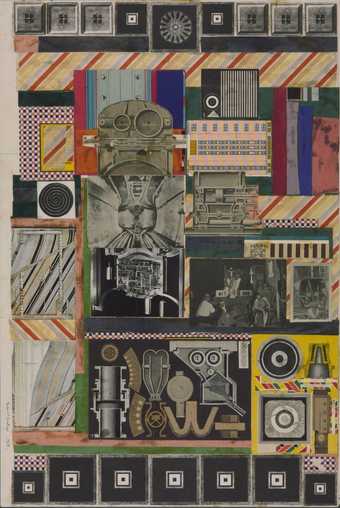

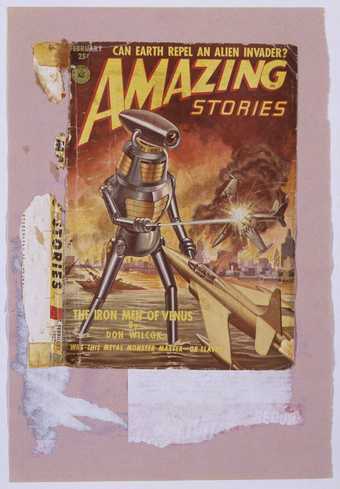

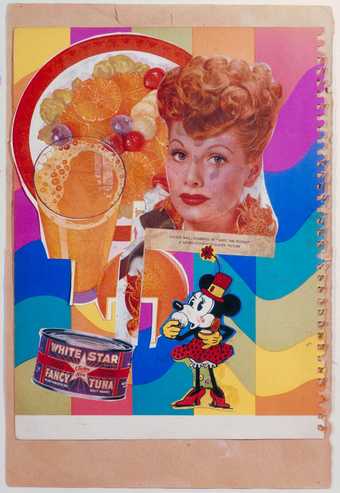

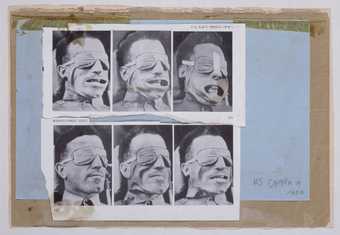

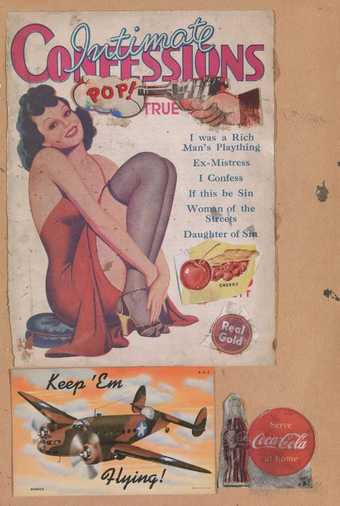

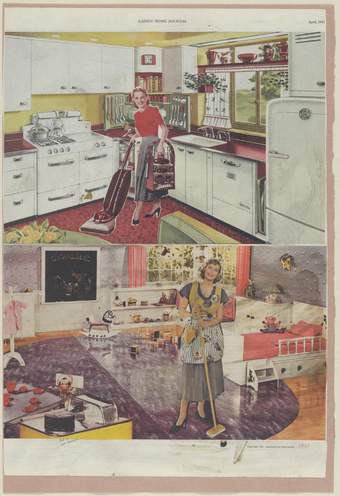

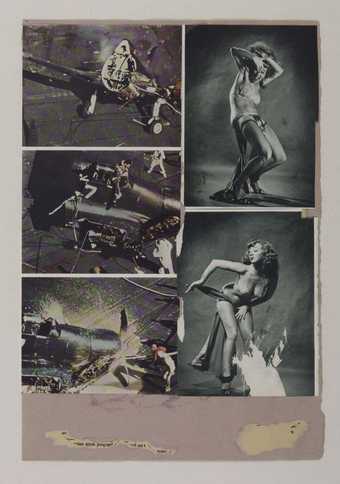

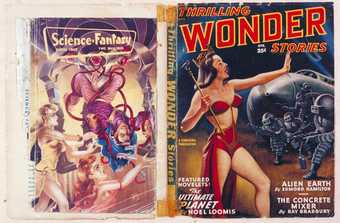

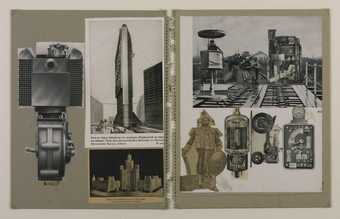

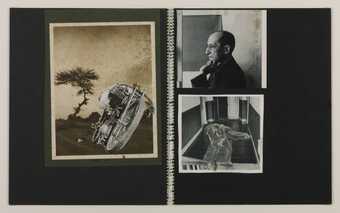

The ten collages T01458 to T01467 are from a larger group, consisting of some of the collages Paolozzi made between 1941 and 1952, and collectively entitled ‘Bunk’. This title was derived from a detail of one of the collages in the group, ‘Evadne in Green Dimension’ 1952, which contains the printed word ‘BUNK!’. In the catalogue of his Tate Gallery retrospective in 1971, the artist states beside a reproduction of this collage (p. 49) that this word gave the title to the lecture he gave at the Independent Group. This lecture, at the premises of the I.C.A. in London in 1952, was the first event to be presented in the programme of the Independent Group. Its main feature was the projection by Paolozzi through an epidiascope of a large number of images mainly removed from magazines and including material from science fiction, aviation, technology, comics, advertising for food, domestic appliances, cars, films, etc., pin-up pictures, news photographs and medical diagrams. Although many of the images projected were whole pages from magazines, untampered with except by the act of isolation, the artist told the compiler that the collages from ‘Bunk’ were among the material that was projected.

In 1972, reproductions of forty-five of the ‘Bunk’ collages were published by Snail Chemicals (Publishing), in two editions comprising a total of 170 sets. The ten images of which the original collages are in the Tate Gallery have the following numbers in this portfolio: T01458 (9); T01459 (10); T01460 (15); T01461 (22); T01462 (25); T01463 (33); T01464 (36); T01465 (43); T01466 (6); T01467 (4).

In the introductory essay to the ‘Bunk’ suite, (loc. cit.), Frank Whitford has written: ‘Bunk occupies a crucial position in Paolozzi’s own development. It is the strongest link between his past and his present. For the kind of imagery he collaged and collected here during the late 1940’s has recurred with marked regularity throughout his work… Bunk is ... a much-thumbed source-book and the key to many of Paolozzi’s otherwise arcane ideas.’

Paolozzi’s note of the date of each ‘Bunk’ collage was printed beside its reproduction in the catalogue of his 1971 Tate Gallery retrospective. He explained to the compiler how each of the very strong images was clearly linked in his memory with specific dateable events such as exhibitions, his return to London from Paris, or different periods of his work as a teacher. In conversation with the compiler (20 July 1971) Nigel Henderson recalled being shown the ‘Bunk’ collages by Paolozzi in the 1940’s and early 1950’s before the Independent Group lecture.

The collages were executed in scrapbooks, in which they remained until shortly before Paolozzi’s 1971 retrospective. It has not been possible to trace whether the particular scrapbooks containing ‘Bunk’ collages were ever exhibited as scrapbooks.

Since childhood, Paolozzi had compulsively filled scrapbooks. In the text of a monograph on Paolozzi to be published in 1973, Frank Whitford identifies influences on Paolozzi subsequent to childhood which joined with this compulsion to stimulate the creation of the ‘Bunk’ collages. Primary among these was the strong impact on Paolozzi of Surrealism, especially when he was in Paris in 1947–49. At Mary Reynolds’s house there he saw a wide range of collaged material including collages by Duchamp from material in the National Geographic Magazine. He was influenced by the collages of Ernst and, through magazines, by those of John Heartfield. The impact of these art influences fused with that of American magazines; Paolozzi acquired these from American G.I.’s in Europe, and from East End shops in London (including S. Lavner’s in Bethnal Green Road, photographed by Nigel Henderson circa 1950–51), he got sex and cinema magazines, and comics. In the ‘Bunk’ suite introductory essay (loc. cit.) Frank Whitford wrote that through American magazines Paolozzi ‘realised that, say, food and automobile ads spoke more eloquently and economically of dreams than any conventional art was able to do’.

The title of each collage in ‘Bunk’ was designated by Paolozzi in 1972. He told the compiler that the collage element containing the word ‘Pop!’ in T01462 came from the packet of a toy gun. The circle-enclosed brand name ‘Real Gold’ which gives its title to T01460 (in which it occurs twice) is also one of the collage elements in T01462. The collage elements in T01466 are placed on a Miró reproduction which Paolozzi identified to the compiler as having been taken from a copy of Verve that he was given before he went to Paris in 1947.

In conversation with the compiler he also affirmed that at the time when he was engaged in it he saw the activity of making the collages in ‘Bunk’ as that of making-art. In any or all of its aspects of selection, retention, isolation, juxtaposition and re-presentation, he saw his continuous activity of taking material from the mass media as an implicit assertion of the impossibility of making a positive distinction between art and life. In the introduction to ‘Bunk’ (loc. cit.) Frank Whitford writes: ‘as Bunk is intended to show, the source material is not only raw material, it is also already art. And Paolozzi could never discuss its fascination with elaborate, ornate or any other kind of superficial seriousness. For, unlike the mandarins, he cannot view it from the outside. It is already part of him, much more his culture than Michelangelo, Raphael or Cézanne.’ In the text of his forthcoming monograph on Paolozzi, Whitford adds: ‘Paolozzi has always been an intuitive artist, playing his hunches. He has always worked first and analysed his motives second. He reacted to the ad and magazine imagery as strongly and as emotionally as he had done to cigarette cards and pictures of footballers he had copied as a child. But the difference now was that the Surrealists had taught him that such ephemeral images, the stuff of dreams, need not necessarily be transformed by an artistic imagination to become art, and that it was better to work with what thrilled him as an artist than consciously to work within a respectable artistic tradition and only use what convention taught was permissible.’

Published in The Tate Gallery Report 1970–1972, London 1972.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- geometric(3,072)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- happiness(258)

- cartoon / comic strip(177)

- colour(836)

- diagrammatic(799)

- recreational activities(2,836)

-

- diving(26)

- characters(438)

-

- Minnie Mouse(6)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- swimming costume(102)

- uniform / kit(324)

- instrument, drum(177)

- frankfurter(2)

- tin can(57)

- lifestyle and culture(10,247)

-

- advertising(536)

- cultural icon(63)

- aircraft, military(138)