Walker Art Center (Minneapolis, USA): Multiple Realities: Experimental Art in the Eastern Bloc, 1960s–1980s

- Artist

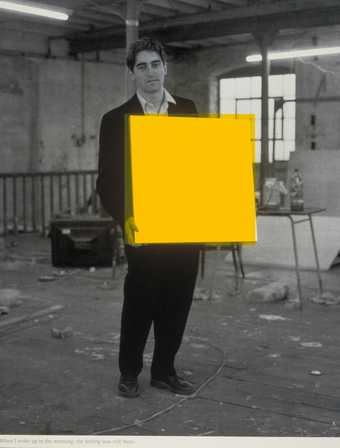

- Roman Ondak born 1966

- Medium

- Performance, people

- Dimensions

- Overall display dimensions variable

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased using funds provided by the 2004 Outset / Frieze Art Fair Fund to benefit the Tate Collection 2005

- Reference

- T11940

Summary

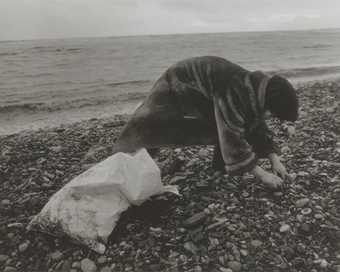

Good Feelings in Good Times is an artificially created queue. It is intended to be performed inside the museum, but can also be adapted to other spaces. The queue is always part of an exhibition and is created in or around an exhibition space. It is formed in front of a spot where it would make sense for a queue to form, or, for an enhancement of its effects, in front of slightly unexpected but not totally irrelevant spots. It can be re-enacted either indoors with a minimum of seven and a maximum of twelve people, or outdoors with a maximum of fifteen people.

Participants of Good Feelings in Good Times are either volunteers or actors hired by the museum and there is no restriction as to their age or gender. They are not required to wear special clothes, but are asked to dress to suit the situation, to hold personal props and look like ordinary people queuing as if waiting for something to happen. If questioned by onlookers, they are not allowed to divulge anything about the performance; they are instead encouraged to improvise as if they were in a real-life situation. The queue is re-enacted repeatedly during the day according to a schedule agreed between the artist and the museum, at set times and spots around the building. Typically, within a forty-minute period of performing, the queue will form, dissolve and form again a few times, with the participants behaving inconspicuously and as naturally as possible. The forty-minute performances may be repeated several times during the day, with twenty-minute breaks in between sessions for the participants to rest, unseen by the general public.

Good Feelings in Good Times was first presented outside the Kölnischer Kunstverein in Cologne, Germany in 2003. The queue was afterwards re-enacted at the 2004 Frieze Art Fair in London, where it was purchased by Tate. Queuing, although a common social activity, is also historically, culturally and, ultimately, behaviourally-contingent. Thus, the work can acquire different connotations depending on the space and time of its enactment. Inspired by the artist’s own memories of the long lines formed outside grocery shops in his native Slovakia in the communist era (Ondák quoted in Andrews), the work probably took on a different meaning at the Frieze Art Fair, where the London location and the busy atmosphere may have evoked more the quintessentially British habit of queuing and the daily suffering of the city’s commuters due to long waits (Anna Colin, Do Not Interrupt Your Activities, exhibition catalogue, Royal College of Art, London 2005, p.69). Re-enacted in Tate Modern, the queue may be understood as drawing attention to the various functions of the institution, or simply giving the artist the platform from which to explore certain larger issues related to queuing that interest him. He has commented:

I became interested in the phenomenon of the queue because it is very unstable, but on the other hand it shows a very strong sense of participation … even if you are not queuing, you are participating as you are facing your memories of queues in the past. There is no description of the queue – it is about feelings, about desire and your decision to be in it, and I like this ambiguity of the queue in our society. Also, on your own you think about your time – what I call ‘real time’ – which has its own value; but when you go in the queue, you slow down and the time is different.

(Ondák in conversation with the author, 16 October 2004.)

Through the notion of the queue Ondák could be said to explore simultaneously the fluctuation between personal time (‘real’ time) and social time (time spent in the queue), past (memories of queuing) and present (actual queuing) and lived experience (being in the queue) and imagined experience (imagining the effects of queuing).

Further reading

Max Andrews, ‘Why Are We Waiting?’, TATE ETC., no.5, Autumn 2005, http://www.tateorg.uk/tateetc/issue5/privateview5.htm, accessed 17 March 2009.

Jessica Morgan and Catherine Wood (eds.), The World As a Stage, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2007, p.58.

Roman Ondák, exhibition catalogue, Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne 2004, pp.180–1, 183 and 198.

Evi Baniotopoulou

March 2009

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Technique and condition

The installation comprises eight to twelve people positioned in a line varying in shape, length and duration.

The artist has instructed that the volunteers/professional actors are dressed in context with their immediate environment and may handle relevant personal items such as mobile phones, portable music players and newspapers. “They have to look as natural as possible, and act as if they are really queuing somewhere, waiting for something to happen. They are not allowed to divulge any information about the performance, so they need to have been briefed/instructed on that beforehand” (artist questionnaire received November 24, 2004).

The work can be displayed in variable locations that make it possible to queue

Jodie Glen-Martin

June 2005

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- universal concepts(6,387)

-

- ambiguity(310)

- artifice(96)

- dysfunction(40)

- humour(1,441)

- recreational activities(2,836)

-

- reading(400)

- waiting(79)

- group(4,227)