- Artist

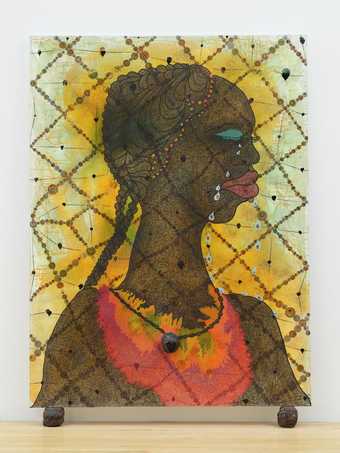

- Chris Ofili born 1968

- Medium

- Oil paint, acrylic paint, glitter, graphite, pen, elephant dung, polyester resin and map pins on 13 canvases

- Dimensions

- Support, each: 1832 × 1228 mm

support: 2442 × 1830 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with assistance from Tate Members, the Art Fund and private benefactors 2005

- Reference

- T11925

Summary

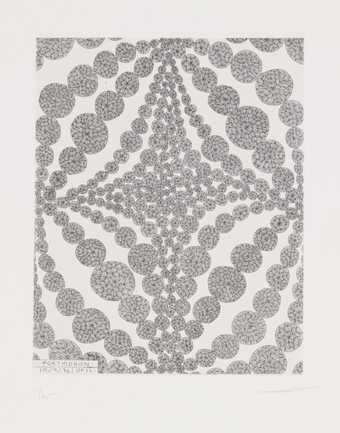

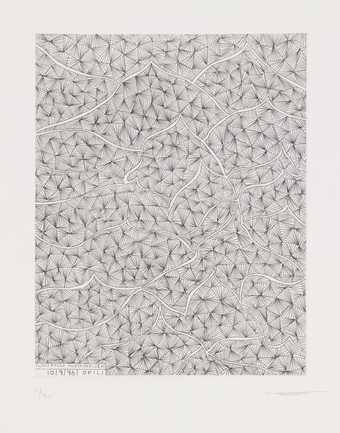

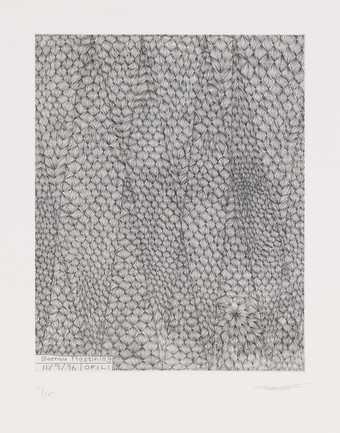

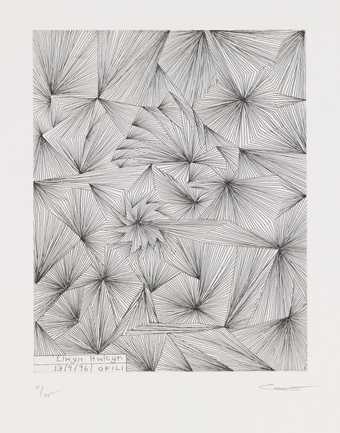

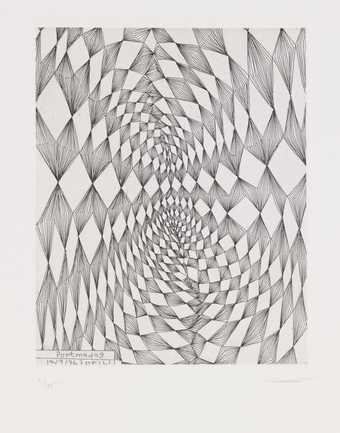

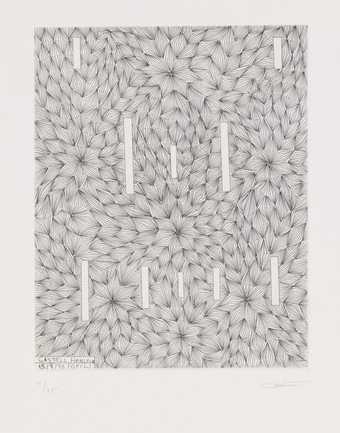

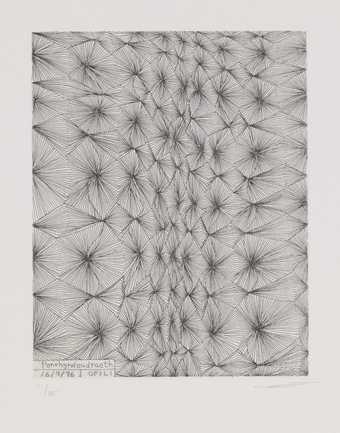

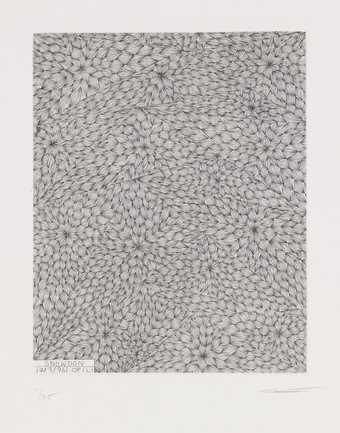

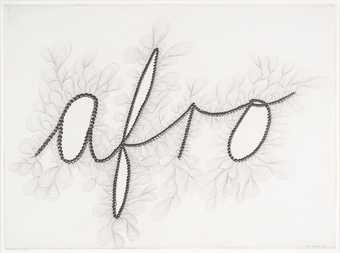

The Upper Room is an installation consisting of thirteen large paintings displayed in one room, each depicting a rhesus macaque monkey. In twelve of the paintings, the monkeys share the same pose: each is seen in profile sitting in a jungle or forest scene and with its tail curled up in the air. These monkeys wear hats, waistcoats and jewels, and each raises a chalice-like vessel in one hand. In six of these paintings the monkey is seen from its left side, while in the other six it is seen from its right side, and the two sets of paintings are positioned along the two long opposing walls of the rectangular room, so that all of the monkeys are facing towards the thirteenth painting, which is much larger and shows the monkey from the front. Each painting in The Upper Room has a different palette that is dominated by one main tone, and they feature dynamic patterns and varying surface textures: as well as a mixture of oil, acrylic, graphite, ink and polyester resin, the canvases are adorned with glitter, gold leaf and map pins. From the surface of each painting protrudes one lump of elephant dung featuring a large spot of paint in that picture’s main colour, and the paintings’ individual titles include the Spanish word for its specific tone – for instance Mono Verde, or ‘Green Monkey’. These titles are written on two further balls of elephant dung on which the bottom edge of each painting rests, with the top edge leaning against the wall of the room. The only lighting in the room is a set of bright spotlights that illuminate the paintings from above, and this room is accessed via steep staircase leading to a long corridor that is dark except for a line of spotlights that runs along one side at ground level. The walls, floor and ceiling of the passageway and the room containing the paintings are covered with walnut veneer panels.

The installation was made by the British artist Chris Ofili in London in 1999–2002. He originally produced the paintings as separate works but later decided to incorporate them into this installation, which was first displayed at Victoria Miro Gallery in London in 2002 as part of a solo exhibition of the artist’s work entitled Freedom One Day. Ofili designed the room and passageway for the installation in collaboration with the British architect David Adjaye. Ofili has described his decision to work with Adjaye as follows:

I had the idea for the space when I was part of the way through the process of making the paintings. The two needed to work hand-in-hand. I made some sketches for a room, but I didn’t feel that I could design a space that would work well with the paintings, and allow for a viewer to have a total experience of looking at the paintings and revelling in that feeling, which is why I asked David [Adjaye] to help me.

(Quoted in Nesbitt, Enwezor, Eshun and others 2010, p.98.)

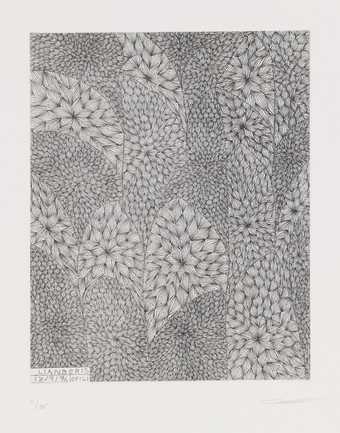

Ofili first used the motif of the monkey carrying a chalice in another painting he had been working on at the time, Monkey, Magic – Sex, Money and Drugs 1999. In this painting and in those he made for The Upper Room, the monkey is created using tiny dots of coloured paint. This was a technique that Ofili adopted following a research trip to Zimbabwe in 1992, when he visited the prehistoric San caves in the Matobo Hills and was inspired by the dotted painting method that was used to make them.

The paintings’ individual titles are a pun on the similarity between the Spanish term for monkey, ‘mono’, and the English word ‘monochrome’. The ‘upper room’ of the installation’s overall title refers to the place in which Christ and his twelve disciples met for the biblical Last Supper. This association with the Last Supper is also reflected in the paintings’ arrangement, in which the larger picture, Mono Oro (‘Golden Monkey’), is placed at the end of the room as if at the head of a table, while the monkeys that face Mono Oro in the twelve smaller paintings raise chalices towards it. The macaque in the larger picture is painted in gold, lending it an opulence that is similar to a church altarpiece. Furthermore, the room’s lighting further evokes a religious setting: its heavy contrasts between dark and light are reminiscent of church interiors, and the bright overhead spotlights project colourful reflections of the paintings onto the floor that are similar to the effect of stained glass windows. Ofili places these references to the Christian faith alongside those of other religions and cultures: elephant dung is considered a symbol of fertility in Nigeria, and the monkeys could refer to the Hindu deity Hanuman, who often takes the form of a rhesus macaque.

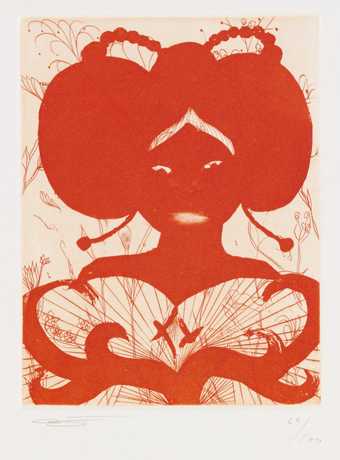

Ofili was born in England to Nigerian parents, and was raised a Roman Catholic. He has often used his work to address faith and the way it is represented across different cultures. In 1996 he made The Holy Virgin Mary (private collection), a painting depicting the mother of Christ as a large-lipped black woman surrounded by collaged fragments of pornographic photographs and with a lump of elephant dung representing her right breast. In challenging portrayals of the Virgin Mary as a white, Western woman, and by accompanying her image with sexualised pictures and with Nigerian spiritual iconography in the form of the elephant dung, Ofili questioned the strict pictorial conventions of Christian art. Despite also including elephant dung and clear references to Christianity, The Upper Room strikes a different tone to The Holy Virgin Mary that stems from Ofili’s longstanding interest in the Last Supper. Ofili stated in 2010 that he had ‘imagined it countless times, what it must have been like in that room’ (quoted in Nesbitt, Enwezor, Eshun and others 2010, p.97) and that in The Upper Room ‘it was important for the space to feel akin to a space of worship’ (quoted in Nesbitt, Enwezor, Eshun and others 2010, p.98).

The Upper Room was purchased by Tate from the Victoria Miro Gallery in 2005. The acquisition caused controversy due to the fact that Ofili was a member of Tate’s Board of Trustees at the time. In 2006 Tate was censured by the Charity Commission, which nonetheless ruled that despite institutional wrongdoing, the work could remain in the collection.

Further reading

Chris Ofili: The Upper Room, exhibition catalogue, Victoria Miro Gallery, London 2002.

Judith Nesbitt, Okwui Enwezor, Ekow Eshun and others, Chris Ofili, London 2010, pp.17–18, 83–95, reproduced pp.80–1.

David Adjaye, ‘Chris Ofili: The Upper Room’, Chris Ofili, New York 2009, pp.122–41, reproduced pp.123, 127–9, 131–5, 137–9.

Fiona Anderson

May 2014

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- irregular forms(2,007)

- formal qualities(12,454)

- public and municipal(956)

-

- art gallery(245)

- chapel(32)

- religions(181)

-

- Christianity(2,755)

- social comment(6,584)

-

- civilisation(222)