- Artist

- Chris Ofili born 1968

- Medium

- Oil paint, acrylic paint, graphite, polyester resin, printed paper, glitter, map pins and elephant dung on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 2438 × 1828 × 51 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1999

- Reference

- T07502

Summary

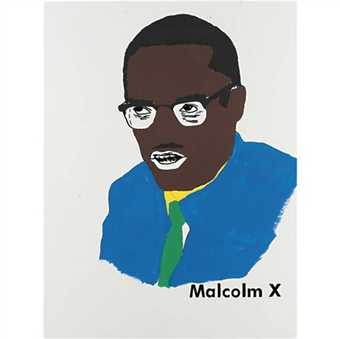

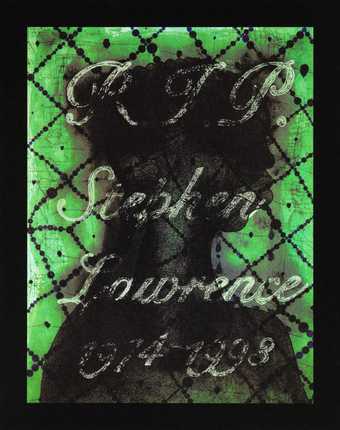

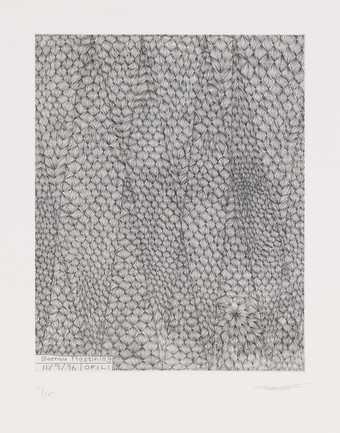

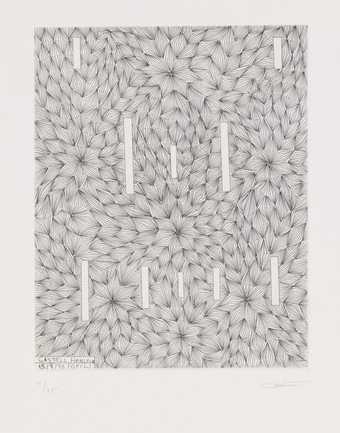

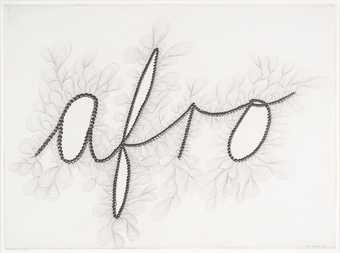

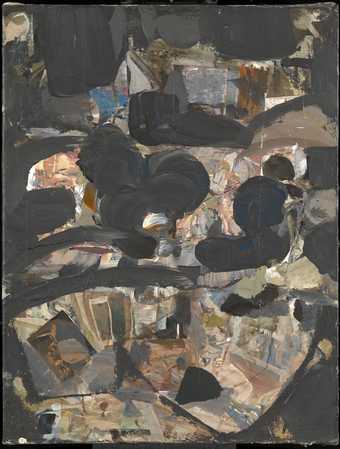

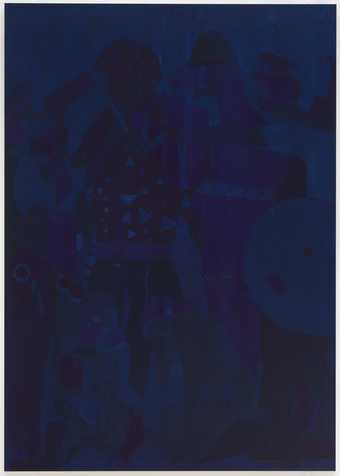

No Woman, No Cry is a very large, densely layered painting that depicts a crying woman set among various abstract patterns. The woman, who has dark hair and black skin and is shown in profile, is formed from a thin brown painted outline that is filled with many small dark brown circles. She wears blue eye shadow, red lipstick, a string of coloured beads that sits just below her hairline and a thin black necklace. Forming the pendant of her necklace is a lump of elephant dung containing map pins, and the woman’s chest bears an area of vibrant red and orange paint, with flame-like yellow forks across its top edge. A series of pale blue tears descends from each of her eyes, all of which feature at their centre a very small collaged photograph of a boy’s face. The background is painted with a mixture of pale green and bright yellow, criss-crossed by conjoined sequences of circles that each contain concentric rings and are gathered to form the rough outlines of diamond shapes. Layered among these are dotted lines punctuated by black heart shapes that appear at the centre of each of the diamonds. Running in four horizontal lines across the canvas, the words ‘RIP Stephen Lawrence 1974–1993’ appear very faintly underneath its top layer, with the dates at the bottom completely obscured by the shoulders of the woman. When exhibited, the painting rests on two large lumps of elephant dung that are placed on the floor, while its upper edge leans against the gallery wall.

This painting was made by the British artist Chris Ofili in 1998 when he was living and working in London. The title of this work is the name of a 1974 song by the Jamaican reggae musician Bob Marley that entreats a female listener not to be sad. The phosphorescent inscription in the painting indicates that the crying woman depicted is Doreen Lawrence (now Baroness Lawrence of Clarendon OBE), the mother of Stephen Lawrence, who was murdered as a teenage boy in an unprovoked racist attack in London in 1993, and the photographs inside the tears in this work are all images of Stephen. After five years of campaigning by Lawrence’s parents, the home secretary, Jack Straw, announced a judicial inquiry into the police investigations into their son’s death. When it was published two years later the 1999 Macpherson Report found police conduct had been marred by professional incompetence and institutional racism. The report made seventy recommendations, which led to an overhaul of Britain’s race relations legislation. Curator Judith Nesbitt has written that ‘Ofili was deeply moved by the way in which Doreen Lawrence’s overwhelming silent grief at her son’s tragic death had been transformed with each successive interview as she became even stronger in spirit and emboldened to speak with great dignity’ (Judith Nesbitt, ‘Beginnings’, in Tate Britain 2010, p.16).

The work is painted on a coarse linen canvas that was bought pre-primed. Ofili added several further layers of acrylic gesso primer and then covered the entire canvas with phosphorescent light green acrylic paint. He then drew lines over it in pencil, before adding the collaged circles that make up the diamond pattern, which are cut from a reproduction of a work by the British abstract artist Bridget Riley. Ofili then applied the heart shapes in black oil paint and the black dots using rub-on transfers. Following this, he used more phosphorescent paint to write the text across the painting, before fixing the dung pendant onto the canvas with a glue gun. A polyester resin mixed with orange and black pigments and glitter was then poured onto the work while it was positioned horizontally, and the canvas was tipped up before drying, producing runs of resin that are visible around its edges. Finally, oil paint thinned with turpentine was applied to depict the woman and unthinned oils were used for the beads and the colours on her chest.

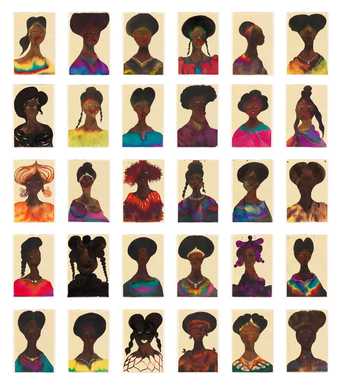

This work was made during a period of Ofili’s practice, beginning in 1996, in which he shifted from making predominantly abstract paintings with scattered representative elements to pictures that primarily focus on large individual figures. More specifically, it is one of a number of paintings he made in 1998 and 1999 that depict black women from the chest upwards (see also Dreams 1998). While these works share many traits with his other large paintings of the 1990s, including the use of elephant dung, dots and multiple layers, their tender tone is notably different from the cartoonish, grotesque and even pornographic manner in which black figures are represented in many of his works from slightly earlier in the decade, such as Rodin … The Thinker 1997–8.

The dense layering of materials is common in Ofili’s paintings from the 1990s (see, for instance, Third Eye Vision 1999, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis). In 2009 Ofili stated that this stemmed from his tendency in the late 1980s to proceed by ‘painting and then scraping down and working on [the canvas] again ... often in the end a finished painting would be constructed from lots of other paintings underneath … I tried to think of a way of working where all of those layers could coexist without cancelling each other out ... All of what comes before is just as important as the statement on top. This was a way of trying to make paintings that has no hierarchical statements within them, despite the fact that a motif often appears to dominate these paintings’ (Thelma Golden and Chris Ofili, ‘Conversation’, in Doig, Becker, Adjaye and others 2009, p.235).

Further reading

Chris Ofili, exhibition catalogue, Southampton Art Gallery, Southampton 1998.

Peter Doig, Carol Becker, David Adjaye and others, Chris Ofili, New York 2009, reproduced p.102.

Chris Ofili, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, p.16, reproduced pp.16, 45.

David Hodge

June 2015

Revised by Clarrie Wallis

April 2018

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Online caption

No Woman No Cry is a tribute to the London teenager Stephen Lawrence who was murdered in a racially motivated attack in 1993. A public inquiry into the murder investigation concluded that the Metropolitan police force was institutionally racist. In each of the tears shed by the woman in the painting is a collaged image of Stephen Lawrence’s face, while the words ‘R.I.P. Stephen Lawrence’ are just discernible beneath the layers of paint. As well as this specific reference, the artist intended the painting to be read as a universal portrayal of melancholy and grief.

Technique and condition

The painting was executed on a single piece of rather coarse linen fabric that is stretched extremely tightly around an eight-membered rigid strainer and attached with stainless steel staples along the rear edges. For display the painting is placed on two lumps of elephant dung (which have been sealed in polyester resin) and is allowed to lean back against the wall. The linen fabric was purchased pre-primed (with an acrylic-based emulsion gesso), but the artist applied further acrylic gesso primer to the stretched face and tacking edges. Despite the many layers of ground, the overall thickness is still sufficiently thin for the canvas weave texture to remain apparent through it.

The first layer of paint was a very light yellow-green imprimatura (this is a phosphorescent paint that glows in the dark). The image was then applied using a variety of different materials. The actual paint used was a combination of oil (painted dots and dark brown outlines) and acrylic emulsion (black hearts). Other materials used were polyester resin, collage, glitter stars and spots, map pins and (sealed and dried) elephant's dung. The order of application was as follows: First the pencil lines were applied, followed by the collaged elements which were adhered to the surface. Then the black hearts were painted in acrylic. The phosphorescent paint was then used to write the words ‘RIP Stephen Lawrence 1974–1993’ in four lines across the surface. This is particularly visible in UV illumination or if viewed in the dark after it has been lit or irradiated with UV. The map pins were inserted into the pieces of elephant's dung which were then stuck to the canvas with a hot glue gun. Then the surface of the painting was flooded with the polyester resin, which bonded the pieces of dung in place. The glitter pieces were sprinkled into the resin before it dried. This part must have been carried out with the painting horizontal, using a tipping technique to produce the runs of resin towards all four edges. Once the resin had dried, the dark brown outline was painted and finally the coloured dots applied. These could have been applied using a dried brush or small stick to position the dots carefully and control the amount of paint. The oil paint would have probably been thinned slightly to improve its flow properties.

The painting is currently in good condition. However, its behaviour in the long term is hard to predict with so many different materials being used. It will therefore be closely monitored at fairly frequent intervals and the amount of travel should be minimised. The weakest part of the structure is the dung pieces on the actual work, which will probably fall off at some point. It is also not known how well the pieces of dung are sealed in the polyester resin and for how long this will prolong their natural deterioration. The artist has left instructions should they ever need replacing. They do not need to be exact copies, but should be remade from dried elephant dung from London Zoo.

Tom Learner

July 2000

Film and audio

Features

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- geometric(3,072)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- grief(125)

- photographic(4,673)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- necklace(108)

- actions: expressive(2,622)

-

- weeping(68)

- head / face(2,497)

- tear(16)

- black(796)

- individuals: male(1,841)

- birth to death(1,472)

-

- mourning(95)

- murder(83)

- inscriptions(6,664)

-

- phrase(100)