- Artist

- Mike Nelson born 1967

- Medium

- 15 rooms, lights, columns, chairs, mirrors, printed papers and other materials

- Dimensions

- Overall display dimensions variable

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by Tate Members 2008

- Reference

- T12859

Summary

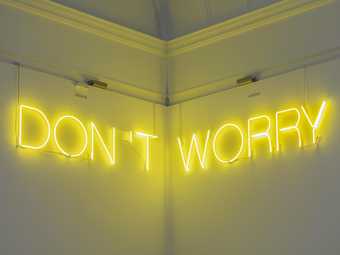

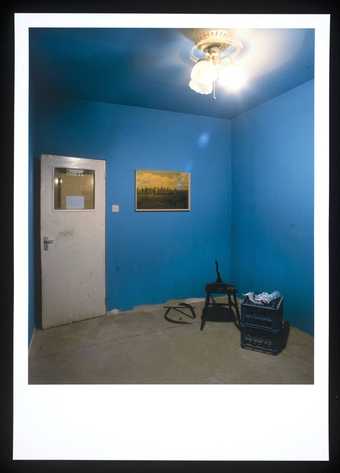

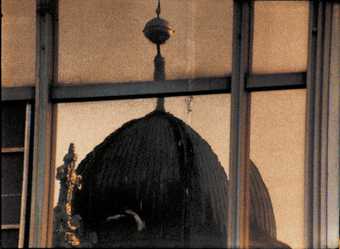

The Coral Reef 2000 is a very large architectural installation consisting of fifteen rooms with connecting corridors. When installed in a gallery the entrance to and exit from its interior are through single doors in the gallery wall, so at no point can the exterior walls of the installation be seen. This ensures that the scale of the installation cannot be deduced from the outside. Upon entering the installation, visitors arrive in what looks like a waiting room. This leads to a shabby-looking cab office with a calendar from the Muslim Association of Nigeria attached to its wall. Beyond this point, visitors can move as they wish among a network of poorly lit and dusty passageways leading to other rooms. Despite displaying signs of occupation and use – the rooms contain furniture and various objects, while lights and screens have been left switched on – the inhabitants of the highly dilapidated and enigmatic space are nowhere to be seen. Only other visitors are encountered along the way and it is unclear from the plethora of items in each room – which visitors are not allowed to touch – who the occupants might be or what they might do. Several of the rooms are loosely themed: there is a security surveillance office, a mechanic’s garage, a room littered with drug paraphernalia, a wood-panelled lobby decorated with Americana and other spaces containing various items including advertisements for a religious gathering, Soviet English-language propaganda, a toy gun, a clown mask and an empty sleeping bag. The final room of the installation is an exact replica of the waiting room that appeared at the beginning. There is no prescribed route through the installation and visitors are allowed to spend as much time inside as they like, although entry is restricted to a small number of people at any one time.

The Coral Reef was made by the British artist Mike Nelson and first installed by the artist and a small team of assistants at Matt’s Gallery in London during the final three months of 1999, opening to the public in January 2000. Most of the installation is made up of found objects collected by the artist. Nelson has explained that the work came about

from repeatedly walking past a mini-cab office around the corner from where I was living in Balham [in London]. The aesthetic was interesting because of the makeshift way such spaces were built and then inhabited. There’d be only a few objects or posters, but through them you could both recognise that these people were quite transient in terms of what they were doing there and also get an idea of what their identity was. These spaces were always spaces which were a front for something else; you would get a glimpse into a back room or of a door that led somewhere, that put you somewhere else … So there was the idea of a sequential series of rooms which were all receptions that never led to anything.

(Nelson in Wallis, accessed 21 August 2014.)

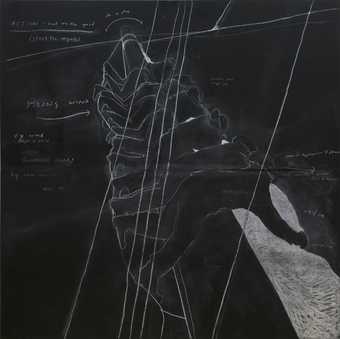

The title of the work, The Coral Reef, makes reference to the large natural structures that lie under the sea. Nelson has connected this to the underlying structures of beliefs – whether religious, political, social or economic – that individuals hold in a way that is mostly subconscious. The artist stated in 2001 that ‘The Coral Reef for me was indicative of a complex but fragile structure of belief systems that exist below the surface of a prevalent ideological structure, of capitalism. In a sense, the sequence of receptions areas are all representative of a different structure of belief’ (Nelson in Wallis, accessed 21 August 2014). Furthermore, Nelson has explained that the feeling of confusion and disorientation that viewers experience in the network of rooms is an analogy for the fact that belief, while giving individuals an illusion of freedom, is in fact deeply restrictive:

All these different belief structures – whether mainstream or non-mainstream religions, or to do with drug- or alcohol-induced states – encourage some idea of escape. In the end, ideas of escape lead to entrapment, which The Coral Reef ultimately does to you as well. You become entrapped within the labyrinth of corridors and rooms while trying to find your way.

(Nelson in Wallis, accessed 21 August 2014.)

According to the art historian Claire Bishop, Nelson’s installation works are ‘a complicated web of references to film, literature, history and current affairs’ (Bishop 2005, p.44). Nelson cites the American writer William S. Burroughs’s 1959 novel Naked Lunch as inspiration for The Coral Reef, specifically its fictional location ‘Interzone’, a dreamlike space that exists between other places. This is reflected in The Coral Reef in the lack of a clear purpose for the rooms or logical transition between them. Another influence for The Coral Reef is the Polish science fiction novelist Stanislaw Lem’s A Perfect Vacuum (1971), which takes the form of an anthology of reviews of imaginary books, the first chapter of which is a review of the book itself. Nelson has explained that the self-referential nature of Lem’s novel was the structural basis for his replication of the first reception room at the end of the installation. In this way, The Coral Reef uses non-linear narrative techniques borrowed from literature to create a disorienting, almost cinematic situation for the viewer in which he or she is automatically implicated on entry to the space, a practice that the curator Nicholas Cullinan has described as ‘intertwin[ing] allusion with illusion’ (Cullinan 2008, p.763).

The Coral Reef is the first of several large-scale site-specific installations made up of labyrinthine spaces that Nelson has created since the turn of the millennium. Similar works include Mirror infill, which was first constructed for the 2003 Istanbul Biennial and consisted of a pre-existing interior that was modified to form a network of dark, winding spaces, one of which housed a darkroom in which hung photographs documenting the space’s transformation into an installation. Nelson stated in 2011 that the immersive, participatory nature of these installations was his way of reacting to ‘the prevalence of video installation through the 1990s. People could spend more time watching a video work than looking at an object … which I found frustrating. So to make a work that entrapped you and forced you to spend time within it was important to me’ (Nelson in Wallis, accessed 21 August 2014). Bishop has observed that in this way The Coral Reef also takes a ‘critical stance towards both museum institutions and the commercialisation of experience in general’ and that it ‘represents a return to some of the values that were originally associated with installation art when it came of age in the 1960s: its engagement with a specific site, its use of “poor” or found materials’ (Bishop 2005, p.47).

Further reading

Claire Bishop, Installation Art: A Critical History, London 2005, pp.45–7, reproduced p. 46.

Nicholas Cullinan, ‘Mike Nelson’s “The Coral Reef” (2000)’, Burlington Magazine, no.150, November 2008, pp.763–5.

Clarrie Wallis, ‘Mike Nelson in Conversation’, Tate Etc., no.22, Summer 2011, http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/articles/mike-nelson-conversation, accessed 21 August 2014.

Fiona Anderson

August 2014

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Film and audio

Explore

- architecture(30,960)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- anxiety(1,028)

- ambiguity(310)

- desolation(135)

- menace(209)

- domestic(1,795)

- tools and machinery(1,287)

-

- machinery(179)

- social comment(6,584)

-

- contemporary society(640)

- tyre(28)