- Artist

- Santu Mofokeng 1956–2020

- Part of

- Billboards

- Medium

- Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

- Dimensions

- Image: 298 × 450 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by the Africa Acquisitions Committee 2017

- Reference

- P82115

Summary

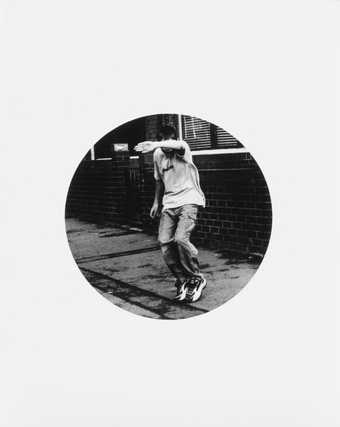

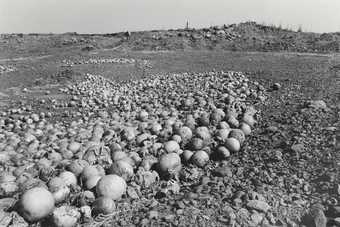

This black and white photograph is from Santu Mofokeng’s series Billboards 1991–2009, a series that draws attention to the omnipresence of advertising posters in various locations around Mofokeng’s native South Africa. Tate has five works from Billboards in its collection: Street Scene – Rockville c.2004, printed 2011 (Tate P82115); Robben Island as You’ve Never Seen It Before c.2002, printed 2011 (Tate P82116); ‘Y’ello Freedom’, Baragwanath Terminus – Diepkloof c.2004, printed 2011 (Tate P82272); Potchefstroom Road, Soweto 2009, printed 2011 (Tate P82273); and A Roadside Sign in Tshwane, Marabastad / Hammanskraal c.2008, printed 2011 (Tate P82117). The photographs in Billboards were taken over a number of years between 1991 and 2009 and printed in 2011 in editions of five plus two artist’s proofs; Tate’s copy of ‘Y’ello Freedom’, Baragwanath Terminus – Diepkloof is number four in the main edition.

The titles of the various images in Billboards indicate the location in which they were taken and at times include quotations from the billboards depicted. In some cases the typography of the billboard itself is the main focus of the image; for instance, in Robben Island as You’ve Never Seen It Before, the slogan of the photograph’s title contrasts with a smaller sign in the foreground that reads ‘Sex is sex: show me the money’. In others, Mofokeng frames the image in order to emphasise how the lifestyle promised in these advertisements can offer a stark, even cruel, contrast to the daily life to which they form a backdrop. In Y’Ello Freedom, Mofokeng has focused on the smiling man in an MTN billboard, while in front of the sign – out of focus but still clearly discernable – are two women struggling under the weight of the large sacks they are carrying.

Mofokeng was born in Soweto, Johannesburg. He began photographing as a teenager, first taking pictures of those closest to him, then taking commissions to document local events and ceremonies. Between 1981 and 1984 he was employed as a newspaper photographer before working for a short time as a photographic assistant in advertising. In 1985 he joined Afrapix, the photographers’ collective and agency founded in 1982 that became the leading proponent of so-called ‘struggle photography’ in South Africa. For Mofokeng, this group – which grew to some forty members – was about ‘taking sides, about photography as activism’ (Santu Mofokeng, in Conversation with Corrine Diserens, in Diserens 2011, p.9). Their activities were more than simply chronicling events: they offered a rigorous critique of documentary practices in a divided country. Although many of the photographs Mofokeng shot during his time with Afrapix were published in newspapers, he has recounted how unsuited he was to the deadline-oriented life of a photojournalist; in part because of his preference for a slower way of working, but also for the practical reason that he did not own a car. While his colleagues competed for space in the darkroom during the day, he took to processing his photographs at night. Working without interruption, he began to think about stories, rather than pressing events: ‘in book terms, not necessarily in newspaper terms’ (Diserens 2011, p.11).

This method of working coincided with his appointment at the African Studies Institute at The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, which, he has said, ‘afforded me the space to think about what was not in the news’ (Diserens 2011, p.12). Beginning with the series Train Church 1986–8, the photo-essay became the main form in which Mofokeng presented his photographs. It enabled him to capture stories that slipped between the binaries ‘of oppression and repression’ repeated in the media: ‘the only way I could show both the good and the bad was in an essay. It allowed for – not balance – but complexity.’ (Mofokeng 2011, p.16.) Discussing the importance of the photo-essay for his art, he has credited the influence of Life photographer W. Eugene Smith (1918–1978), who came to prominence in the 1950s for his work in this mode. While Mofokeng has remained faithful to this format throughout his career, two events in the early 1990s prompted him to reassess the manner in which he approached his subject matter. The first was a comment left in the guestbook at his exhibition Like Shifting Sand at the Market Galleries, Johannesburg in 1990, which accused him of ‘making money from blacks’. The second was his attendance at the International Center of Photography, New York in 1991 as recipient of the prestigious Ernest Cole Award. There, in workshops led by photographers Roy de Carava and Brian Weil, he was encouraged to reconsider the editorial nature of his work.

From this point on, Mofokeng developed a more research-led approach. He started to investigate the photographic archive, culminating in the slide projection The Black Photo Album/Look at Me 1997 (Tate T13173) and the series Distorting Mirror/Townships Imagined 1992. He also began to make series of photographs wherein images were linked by a conceptual framework, as opposed to offering a narrative about a specific moment in time or place. The politics of representation – more specifically, concerns about disparity between those depicted and those who attended his exhibitions – also became an important concern.

Throughout his career, Mofokeng has maintained his focus on townships. Billboards is a statement about power and oppression; the relationship between, in his words, ‘ruler and denizen’:

The billboard is a fact and feature of the township landscape. It is a relic from the times when Africans were subjects of power and the township was a restricted area; subject to laws, municipality by-laws and ordinances regulating people’s movements and governing who may or may not enter the township. It is without irony when I say that billboards can capture and encapsulate ideology, the social, and economic and political climate at any given time. They retain their appeal for social engineering.

(Quoted in Diserens 2011, p.168.)

In the series Mofokeng traces how the changing social and political climate in South Africa was reflected in the billboard: from early-apartheid era signs that were chiefly concerned with ‘sanitation syndrome’ (a term used by historian Maynard Swanson to describe how medical and other public officials in South Africa appropriated medical imagery as a mechanism for societal segregation); to 1960s-era American-style highway billboards that coincided with an economic boom; to the overtly political posters of the 1970s and 1980s. He has also observed the proliferation of the government’s ‘loveLife’ HIV/Aids awareness campaign posters, and described them as ‘crude, pervasive, provocative and obtuse’ (Diserens 2011, p.168). Billboards also includes the advertisements by local entrepreneurs who, Mofokeng describes, are now creating their own signage but without the use of graphic designers or artists, contributing to what he describes as a ‘visual pollution’ that has reduced towns to ‘one large billboard’ (Diserens 2011, p.168).

Further reading

Patricia Hayes, ‘Santu Mofokeng, Photographs: “The Violence is in the Knowing”’, History and Theory, vol.48, December 2009, pp.34–51.

Corinne Diserens (ed.), Chasing Shadows: Santu Mofokeng Thirty Years of Photographic Essays, New York 2011.

Emma Lewis

December 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.