- Artist

- Roy Lichtenstein 1923–1997

- Medium

- Acrylic paint and oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 1727 × 4064 mm

frame: 1747 × 4084 × 60 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1966

- Reference

- T00897

Summary

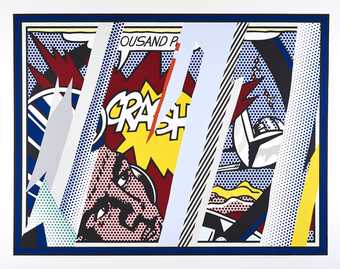

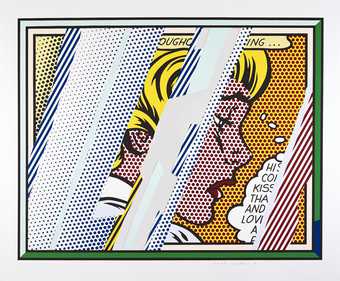

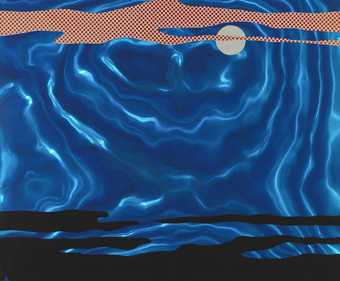

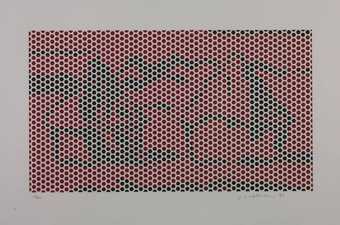

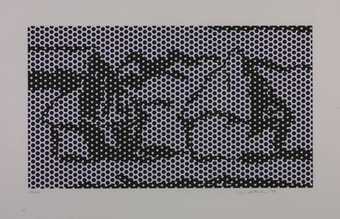

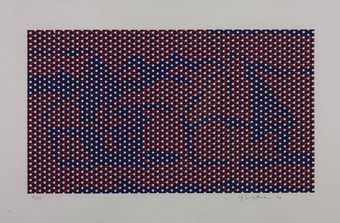

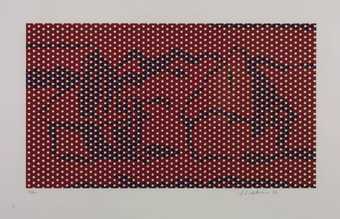

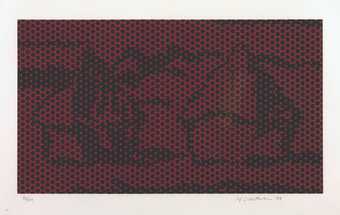

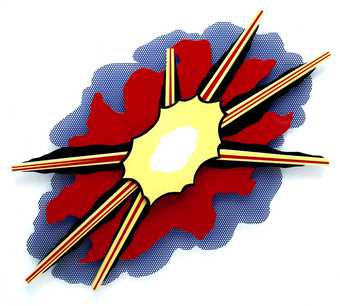

Whaam! 1963 is a large, two-canvas painting by the American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein that takes its composition from a comic book strip. The left-hand canvas features an American fighter plane firing a missile into the right-hand canvas and hitting an approaching enemy plane; above the American plane, the words of the pilot appear in a yellow bubble: ‘I PRESSED THE FIRE CONTROL… AND AHEAD OF ME ROCKETS BLAZED THROUGH THE SKY…’. The outline of the resulting explosion emanates in yellow, red and white; the work’s onomatopoeic title, ‘WHAAM!’, jags diagonally upwards to the left from the fireball in yellow, as if in visual response to the words of the pilot. The painting is rendered in the formal tradition of machine-printed comic strips – thick black lines enclosing areas of primary colour and lettering, with uniform areas of Ben-Day dots, purple for the shading on the main fighter plane and blue for the background of the sky.

The work’s composition is taken from a panel drawn by Irv Novick which appeared in issue number 89 of All-American Men of War, published by DC Comics in February 1962. From the original panel, Lichtenstein produced preliminary drawings, one of which is in Tate’s collection (Drawing for ‘Whaam!’ 1963, Tate T01131). In this drawing, he set out his first visualisation of the painting, including marking the divide of the original single panel into two parts, confining the main plane to one and the explosion to the other. Revealing Lichtenstein’s process of making minor changes during a work’s creation, the colour annotations on the drawing are different to the final colours used in the painting, notably the use of yellow instead of white for the letters of ‘WHAAM!’. To make the final painting, Lichtenstein projected the preparatory study onto the two pre-primed canvases and drew around the projection in pencil before applying the Ben-Day dots. This involved using a homemade aluminium mesh and pushing oil paint through the holes with a small scrubbing brush. Onto this he painted the thick outlines of shapes and areas of solid colour in Magna acrylic resin paint. This use of different materials has made cleaning the painting a particular challenge for conservators (see ‘Conserving Whaam!’, Tate website, 1 March 2018, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/lichtenstein-whaam-t00897/conserving-whaam, accessed 7 November 2018). According to the artist, the diptych took one month to produce from start to finish (Lichtenstein, letter to Richard Morphet, 10 July 1967, Tate Catalogue file).

While Lichtenstein’s work that draws on popular imagery from advertising and cartoons involves a degree of appropriation, the artist himself acknowledged that the act is really one of transformation: ‘I am nominally copying, but I am really restating the copied thing in other terms. In doing that, the original acquires a totally different texture.’ (Quoted in Lawrence Alloway, Roy Lichtenstein, New York 1983, p.106.) By taking the comic strip and using it as he does, he conflates the powerful but so-called ‘low’ mass-produced commercial image with the traditionally venerated medium of large-scale easel painting. Lichtenstein also explained the significance of the military subject matter he chose for many of his paintings during 1962–3: ‘At that time I was interested in anything I could use as a subject that was emotionally strong – usually love, war, or something that was highly-charged and emotional subject matter. Also, I wanted the subject matter to be opposite to the removed and deliberate painting techniques.’ (Lichtenstein in John Coplans, ‘Interview with Roy Lichtenstein’, Artforum, May 1967, p.36.) He saw the style of cartoons, with their easily digestible lines and primary colours, as an appropriate vehicle for painting a dramatic scene in a detached, calculated manner.

The choice of cartoon to represent military action arguably also renders the scene ridiculous and juvenile. Although the intention of the original publication of the comic may have been to show glorious, action-filled images of ‘All-American Men of War’, through Lichtenstein’s quasi-absurdist treatment, the scene is turned into what art critic Alastair Sooke has described as ‘a tongue-in-cheek male daydream of aggression, conquest and ejaculatory release’ (Alastair Sooke, Roy Lichtenstein: How Modern Art Was Saved by Donald Duck, London 2013, p.2). Considering Whaam! was created in 1963, just as the Vietnam War was gathering steam, and taking into account Lichtenstein’s own service in the US Army in 1943–6, this deconstruction of military heroism could be read as a statement on the folly of war. Lichtenstein explored the imagery of explosion in two other works in Tate’s collection, Wall Explosion II 1965 (Tate T03083) and Explosion 1965–6 (Tate P01796).

The content, conceptual basis and production of Whaam! makes the viewing of the work full of contradictory dualities which are never fully resolved – highly charged subject matter rendered in a dispassionate, detached style; commercial art in a fine art context; the mass-produced image painstakingly rendered by hand in a unique painting; the familiarity of the imagery and its alien application in scale and medium. Many of these dualities chime with ideas explored in the wider pop art movement by the likes of Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg.

Further reading

Diane Waldman, Roy Lichtenstein, London 1971, pp.16–17, reproduced p.72.

James Rondeau and Sheena Wagstaff (eds.), Roy Lichtenstein: A Retrospective, London 2012, p.39, reproduced pp.160–1.

Nathan Dunne, Roy Lichtenstein, London 2013, pp.17–18, reproduced pp.40–1.

Arthur Goodwin

November 2018

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Whaam! is based on an image Lichtenstein found in a 1962 DC comic, All American Men of War. Lichtenstein often used art from comics and adverts in his paintings. He saw the act of taking an existing image and changing the context as a way of transforming it’s meaning. Lichtenstein was interested in emotional subjects, such as love and war. His work takes on these themes in a distant and impersonal way.

Gallery label, July 2020

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Roy Lichtenstein born 1923 [- 1997]

T00897 Whaam! 1963

Inscribed on back of left-hand canvas 'rf Lichtenstein | '63' and 'LEFT | PANEL'; on back of right-hand canvas 'rf Lichtenstein | '63' and 'RIGHT | PANEL'; 'WHAAM! | MAGNA & OIL' on both stretchers

Magna acrylic and oil on canvas, 68 x 160 (172.7 x 406.4), (two canvases each 68 x 80 (172.7 x 203.2))

Purchased from Leo Castelli, Inc., New York, through the Galerie Ileana Sonnabend, Paris (Grant-in-Aid) 1966

Exh:

Roy Lichtenstein, Leo Castelli, New York, September-October 1963 (no catalogue); Mixed Media and Pop Art, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, November-December 1963 (60); Salon de Mai, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, May-June 1964 (102, repr.); Nieuwe Realisten, Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, June-August 1964 (95, repr.); POP etc., Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts, Vienna, September-October 1964 (84, repr.); Neue Realisten und Pop Art, Akademie der Kunste, Berlin, November 1964-January 1965 (65); Pop Art, Nouveau Réalisme etc. ..., Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, February-March 1965 (79); Roy Lichtenstein, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, November-December 1967 (22, repr. in colour); Tate Gallery, January-February 1968 (21, repr. in colour); Kunsthalle, Bern, February-March 1968 (20, repr. in colour); Kestner-Gesellschaft, Hanover, April-May 1968 (20, repr. in colour); Roy Lichtenstein, Guggenheim Museum, New York, September-November 1969 (25, repr. in colour)

Lit:

Diane Waldman, Roy Lichtenstein

(London 1971), pp.16-17, repr. pl.72 in colour

Repr:

Aujourd'hui, No.49, April 1965, p.46; The Tate Gallery

(London 1969), p.193 in colour

The artist wrote (10 July 1967): 'I remember being concerned with the idea of doing two almost separate paintings having little hint of compositional connection, and each having slightly separate stylistic character. Of course there is the humorous connection of one panel shooting the other. I know that I got the idea of doing separate panels while working on Tex, so that Tex

and Whaam

are very closely related, and probably come from the same magazine - possibly from the same story. I think that the comic was "Armed Forces at War". I don't keep any records and I think I may have gotten the above information from your letter to me.

'Whaam relates in feeling to the many war paintings I did during 1962-63, including a five panel sequence entitled Live Ammo

which has since unfortunately been resold and divided among four separate owners, the three paneled painting, As I Opened Fire, owned by the Stedelijk [Amsterdam] (which I think is the most recent war painting) and O.K. Hot Shot, owned by The Hague, as well as many smaller works. All of these portray emotionally charged subject matter as it might be reported in the dispassionate style of group decisions, as well as picturing modern methods of exporting economic and social philosophy.'

'Tex' (1962, oil on canvas, 157.5 x 203cm, collection E.J. Power, London) is reproduced in Waldman, op.cit., pl.23. Although a single-canvas painting, it too shows a much-foreshortened fighter plane entering from the (lower) left. The plane has similar markings to its equivalent in 'Whaam!', and similarly a word-bubble emanates from the pilot, the path of a missile beneath its right wing is indicated by a trail of smoke, and a second plane disintegrates in an elaborate explosion to the (upper) right side of the painting.

Several statements made by Lichtenstein on the ideas behind his work especially illuminate the significance of 'Whaam!'. In an interview with John Coplans in the catalogue of Roy Lichtenstein, Pasadena Art Museum, April-May 1967 (reprinted Artforum, May 1967, pp.34-9), he discusses his use of explosions and of popular/commercial idioms: he also states of the time when war imagery appeared in his work: 'At that time I was interested in anything I could use as a subject that was emotionally strong - usually love, war, or something that was highly-charged and emotional subject matter. Also, I wanted the subject matter to be opposite to the removed and deliberate painting techniques. Cartooning itself usually consists of very highly-charged subject matter carried out in standard, obvious and removed techniques.'

In an interview in the series 'What is Pop Art?', in Art News, November 1963, pp.25, 62-3, he discusses the interplay in his paintings between apparent object directedness and actual ground-directedness, and also says: 'The heroes depicted in comic books are fascist types, but I don't take them seriously in these paintings - maybe there is a point in not taking them seriously, a political point. I use them for purely formal reasons, and that's not what those heroes were invented for ... Pop Art has very immediate and of-the-moment meanings which will vanish ... Pop takes advantage of this "meaning", which is not supposed to last, to divert you from its formal content. I think the formal statement in my work will become clearer in time.

Published in:

Ronald Alley, Catalogue of the Tate Gallery's Collection of Modern Art other than Works by British Artists, Tate Gallery and Sotheby Parke-Bernet, London 1981, pp.436-8, reproduced p.436

Film and audio

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- formal qualities(12,454)

- weapons(925)

-

- rocket(6)

- weapon, firing / explosion(81)

- transport: air(271)

-

- aircraft, military(138)

- inscriptions(6,664)