- Artist

- R.B. Kitaj 1932–2007

- Medium

- Oil paint, ink, graphite and paper on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 1530 × 1524 mm

frame: 1550 × 1535 × 55 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1980

- Reference

- T03082

Display caption

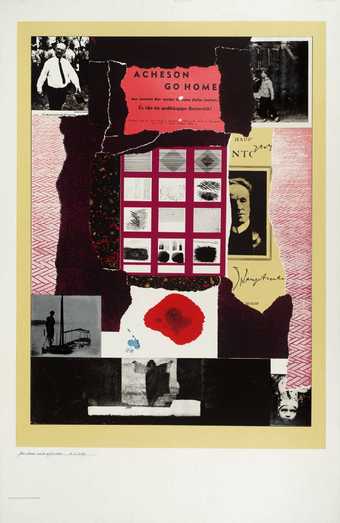

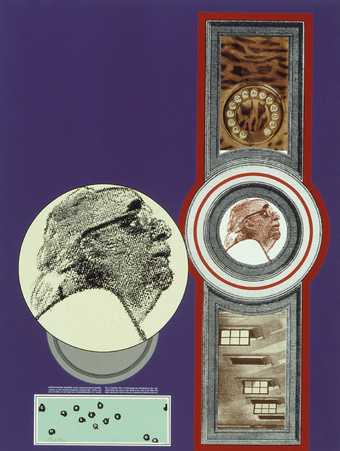

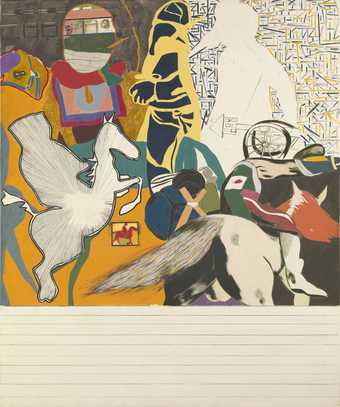

Rosa Luxemburg was a Jewish activist and founder of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). She was killed in 1919 by troops opposed to the revolutionary movement that swept Germany in the wake of the First World War.

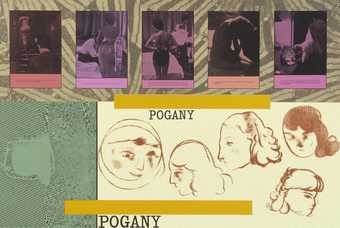

In the centre of the painting a figure holds Luxemburg’s corpse, while at top right is a collaged transcription of an account of the murder. Kitaj associated Luxemburg with his grandmother Helene, who was forced to flee Vienna in the 1930s. The veiled figure at top left represents his maternal grandmother, who fled Russia as a result of earlier pogroms of the Jewish people.

Gallery label, September 2018

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

T03082 THE MURDER OF ROSA LUXEMBURG 1960–2

Inscribed ‘Kitaj’ bottom left

Oil and collage on canvas, 60 1/4 × 60 (153 × 152.3)

Purchased from E.J.Power (Grant-in-Aid) 1980

Prov: Purchased by E.J.Power shortly after its completion

Exh: Arte Inglesi Oggi 1960–76, Palazzo Reale, Milan, February–May 1976 (number 1 of 7 works by Kitaj); R.B. Kitaj, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C., September–November 1981 and subsequent tour to Cleveland Museum of Art, November 1981–January 1982, and Kunsthalle, Dusseldorf, February–March 1982 (5, repr.)

Rosa Luxemburg (1871–1919) was born of a Jewish family in Russian Poland and became a revolutionary theoretician and agitator. She and Karl Liebknecht were among the founders of the German Communist Party in December 1918 following the German revolution a month before. They were both assassinated on 15 January 1919 by troops opposed to the revolution.

In a statement dated ‘Paris 1982’ which he sent to the compiler in August 1982, Kitaj wrote:

'The Murder of Rosa Luxemburg (1960–1962)

'This was a student work, begun while I was at the Royal College of Art. It looks naive and graceless to me now, but the more I contemplate it, the thing begins to assume, in its failings and impatience, at least some of the terms of its genesis, terms which really interested me, and still do 20 years later.

'The picture arose out of a meditation upon two of my grandmothers. (There had been a third.) It is about an historic murder but it is really about murdering Jews, which is what brought my grandmothers to America. One of them, Rose, left Russia because her Ukrainian neighbors regularly liked to kill Jews around the turn of our century. The other grandmother, Helene, left Vienna 40 years later because the Austrians were becoming expert at killing Jews and, in fact, Helene's two sisters (like Kafka's two sisters) were later murdered at Theresienstadt.

'Looking back, it doesn't seem to have been a bad idea at all to have looked around for some case to be put in a picture, some tableau or imaging which could represent the condition of fear and foreboding in which Jews had always lived in the Diaspora before Nazism, and which condition shows little sign of disappearing since the Holocaust.

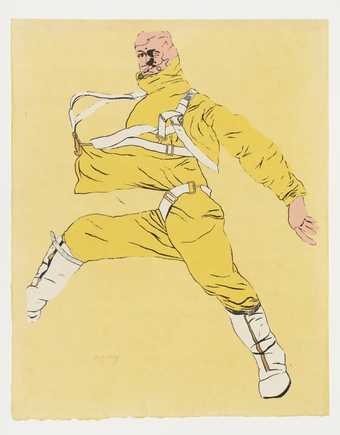

As a student at the Royal College, I came across Rosa Luxemburg's Letters from Prison. Prison letters have always fascinated me but in the great Spartacist Rosa, in her life and in her death, I'd found an ikon for the dark times I associated with my grandmothers. The body in the picture looks very melodramatic but I grew up on tales and photographs of such battered corpses and so the murder (which is retold in the notes attached to the picture) is personified in a form I had seen the like of. Grandma Rose is given as her veiled wraith, upper left, but it is Grandmother Helene who really prefigures Rosa L. (in my life).

Helene and Rosa L. looked alike, dressed alike (the long black dress and boots in the picture were worn by Helene 50 years after her surgeon husband was killed in the Austrian army, during the same Great War which Rosa L. hardly survived), and, more to the point, Helene and Rosa L. were both from that highly cultivated middle class of emancipated Central European Jews, which has, in its brilliance and its disaster written its own legend by now, or history has done. Both had been attacked by the murderous force of hatred for Jews, but as I write these words, Helene Kitaj is still alive in Ohio, at 102 years! She was born (as was Picasso) in 1881, the year Disraeli died, when Dreyfus was still an obscure captain on the French General Staff.

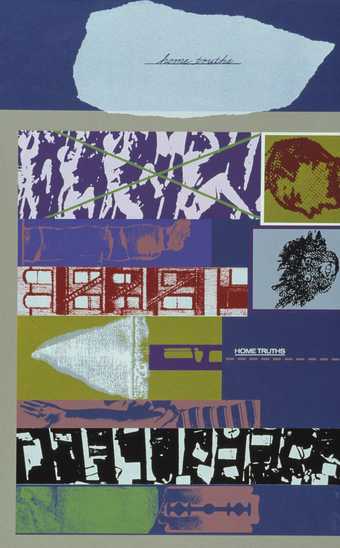

'I can seen in my journal for the period that I could not decide what to call this picture. I had been mooning over Rilke's Duino and my journal tells me I preferred “Elegy” to “Dirge” or “Threnody” because the grandmother theme was to be stated only obliquely (an accursed practice of mine), in the way Rilke was not really mourning the dead, but lamenting human weakness. And so, before the idea of the Banality of Evil became current and controversial (Arendt's Eichmann), I sought to cast my theme in a representation of thugs doing their thing. Thugs rarely act alone. Thuggery is almost defined (at least in my experience) in an unimaginative dependence between dull fellows which is given in the attached note. Another fellowship, suspected by some, is the bonding of Fascism and a degenerated Romanticism, of which National Socialism became, as it were, the ass-end. that bond, too, is suggested in the imagery at the bottom left. Ernest Gellner, in a recent comic aside about World War II, called it the war against German Romanticism! The Romantic Ruin is also mooted in the top left pyramid which prefigures certain pyramidal monuments deliberately created in some Jewish cemeteries in Eastern Europe after the war out of fragments of gravestones. Richard Fein calls them Holocaust Art, in situ, and says that such things are ancient ruins half a century old!

'When I'm not being called a literary painter (and much worse), I've been called a “political” painter. This artless painting was, I guess, my first political picture, but I didn't paint Rosa because I identified with her revolution (or its failure) but, as I've said, for other, oblique reasons. I didn't do it very well. That kind of vision always feels beyond me, but designing such subjects still seems to me an often despised and Empty quarter, all but untouched, and still looking for modern forms of art.’

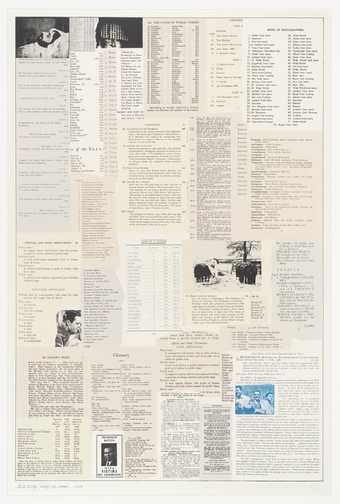

The collage element of ‘The Murder of Rosa Luxemburg’ at the top left reads as follows:

'... Rosa Luxemburg was led from the Hotel Eden by Lieutenant Vogel. Before the/door a trooper named Runge was waiting with orders from Lieutenant Vogel and/Captain Horst von Pflugk-Hartung to strike her to the ground with the butt of his/carbine. He smashed her skull with two blows and she was then lifted half-dead/ into a waiting car, and accompanied by Lieutenant Vogel and a number of other/officers. One of them struck her on the head with the butt of his revolver, and/Lieutenant Vogel killed her with a shot in the head at point-blank range. The/car stopped at the Liechtenstein Bridge over the Landwehr Canal, and her corpse was/then flung from the bridge into the water, from which it was not recovered until/the following May’/(from Edward Fitzgerald's translation of Paul Frölich's ‘Rosa Luxemburg’ .../Left Book Club Edition, Victor Gollancz, 1940)/The bust in the car window bears some resemblance to Field-Marshall Count von Moltke/a figure similar to the image at the left of this sheet surmounts the German national/ monument, Niederweld, commemorating the foundation of the new German Empire/in 1871./The journal of the Warburg Institute, vol.11 number 2 contains a paper by Alfred/Neumeyer called ‘Monuments to “Genius” in German Classicism’. The monument at/the bottom left looks something like a monument to Frederick the Great and/his Generals as seen in an aquatint used in illustration to Neumeyer's paper.’

Published in:

The Tate Gallery 1980-82: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1984

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- figure(2,270)

- military: World War II(1,269)

-

- Holocaust(39)

- corpse(99)

- Jewish(3,752)

- crime and punishment(436)

-

- murder(83)

- exile(1,976)

- refugee(1,995)

- revolutionary(178)

- anti-semitism(35)

- car(502)

- inscriptions(6,664)

-

- quotation(297)