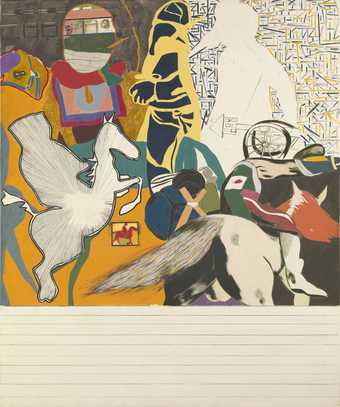

- Artist

- R.B. Kitaj 1932–2007

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 1524 × 1524 mm

frame: 1650 × 1650 × 60 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1974

- Reference

- T01772

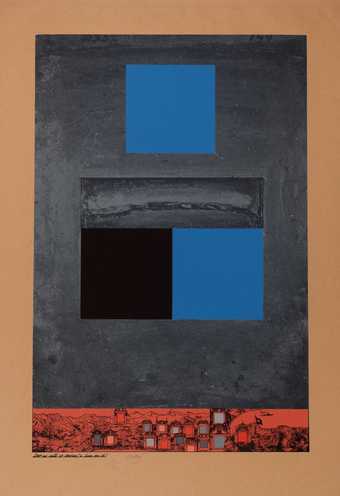

Display caption

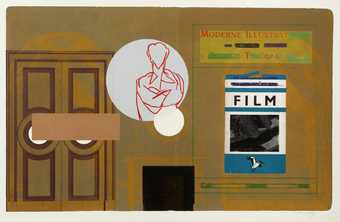

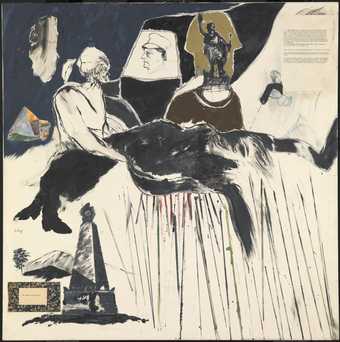

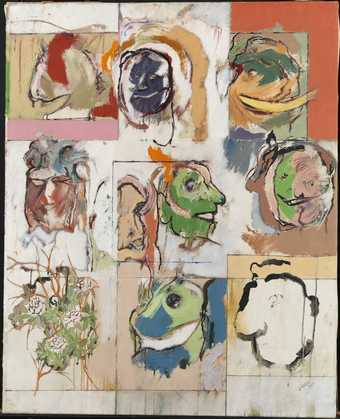

This painting was inspired by a reproduction of an early nineteenth-century engraving of the same title. The engraving was a political satire, though its subject was unknown to Kitaj, and his painting is more concerned with the notion of the idyll and the relationship between two people as characters in a novel. Kitaj stated ‘while I was painting the picture (first six months of 1973) I was deeply reading … Humboldt’s travel in the Orinoco ... I must have been touched some by those wonderful plates you find in those books’.

Gallery label, September 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

R. B. Kitaj 1932-2007

T01772 The Man of the Woods and the Cat of the Mountains 1973

Not inscribed.

Canvas, 60 x 60 (152.5 x 152.5).

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery, 1974.

Coll: Purchased from the artist by Marlborough Fine Art 1973.

Exh: Selected European Masters of the 19th and 20th Centuries, Marlborough Fine Art, (London) Ltd, June–September 1973 (34, repr. in colour); Marlborough Gallery Inc., New York, February 1974 (unnumbered, repr. in colour).

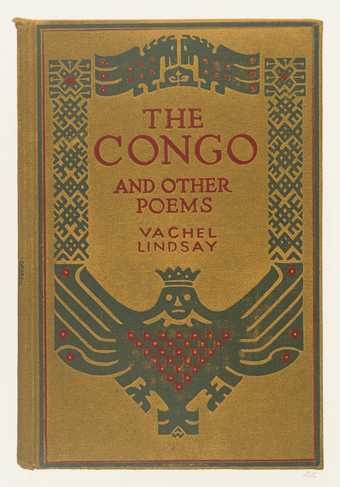

Lit: Frederic Tuten, ‘On R. B. Kitaj, Mainly Personal, Heuristic and Polemical’, in catalogue of the exhibition at Marlborough New York, February 1974, P.7.

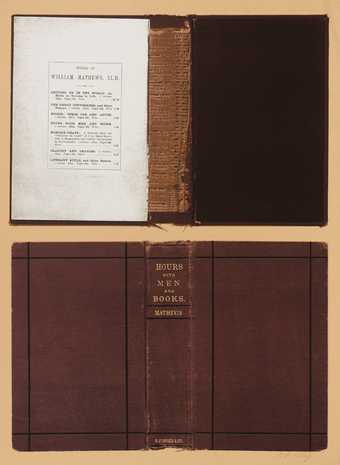

In a letter of 7 May 1974 the artist told the compiler that the painting was inspired by a reproduction, probably from an unidentified print seller’s catalogue, of an early nineteenth-century engraving entitled ‘The Man of the Woods & the Cat-o’-mountain’.

The engraving (M. Dorothy George, Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires Preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum, Vol.x,1820–27, 1952, No.14131) pp.199–200) has been attributed to Thomas Lane. Dated 27 March 1921, it satirises part of the final stages of the unsatisfactory marriage between George IV and Caroline of Brunswick. Here Queen Caroline and Alderman Woods are depicted as cat and ape respectively. Woods was twice Lord Mayor and a staunch supporter of the Queen on her return to London after the death of George iii in 1820, and during the parliamentary enquiry centering on her alleged adultery with Bergami. The two figures sit before a kitchen fire with a ‘Kettle of Fish’ steaming on the hob. Behind them is a dresser with pots and pans, some labelled ‘Hash’, ‘Tinder’, ‘Stew’, ‘Brimstone’, indicating the unpleasant, inflammatory situation now shelved. The Queen had finally accepted the removal of her name from the Liturgy and a financial provision of £50,000 per annum and had ceased to be a subject of political controversy. Among numerous other visual and verbal clues a large chestnut roasting on the fire and labelled ‘St. Catherine’s’ shows that Woods was seeking to become Warden of St. Catherine’s by the Tower, a sinecure in the gift of the Queens of England. An apposite verse by Gay printed below also suggests the origins of the transmogrification of the figures:

‘A Cat and Monkey tired of play,

Basking before the Fire lay,

Pug in the fire a Chestnut spied

Puss lend me your paw, he slyly cried

And we the Booty will divide!!!’

Kitaj has used many of the elements of the engraving in his painting, in particular the two figures, the one holding the paw of the other, the shape of the space and the utensils on the shelves behind them. The title is also given as in the unidentified catalogue: ‘The Man of the Woods and the Cat of the Mountains’. Nevertheless the subject of the engraving was unknown to Kitaj. In a further letter of 20 May 1974 he wrote to the compiler ‘No—I didn’t know about that marriage. I never read into that kind of history, I suppose… and I hardly remember where I found the engraving... I think maybe it is cut from one of those print catalogues I see now and again.’

His letter of 7 May 1974 continued: ‘I really don’t know anything about the engraving beyond what I can surmise or imagine and I would be pleased to think that the painting might insinuate itself beyond its own life as the engraving has.’

‘I thought that the man should be telling the cat that there is a better life out in the world beyond the room.’

‘Yes, the painting seems idyllic and after rejecting features that were intended to make the room look like a miserable place, the idyll set in and though there is still some muted vestige of a meaner life (the things hanging on a clothesline), I did want to make a more magical composition. About the idyll in the context of my work —I have always hoped to be able to show or represent a relationship between people and that hope is still very close to me and I will work to make very much clearer and more specific examples and characters as in novels.

‘I might have been more pleased to be able to say that the picture appeared less timeless... but I’m afraid you are right about that as well.’

‘I had hoped to gather some things around the figures like attributes to replace the crockery and polemical excuses in the engraving and I intend to make an etching based on the same engraving in which I can hope to develop attributes for another version of the couple which may carry more meaning than the props in the painting... I have always enjoyed Pound’s clear demarcation between a symbol which exhausts its references and a sign or mark of something which constantly renews its reference. In that light some of the attributes appear more ambiguous than others... the circular thing was inspired by a loudspeaker in a still from an early Soviet film: Fragment of an Empire directed by A. Ermler, about a man who loses his memory under the Tsarist regime and regains it under new social conditions... ‘The man’s face was taken from a study I have of George Sand... the cat’s face I made up.’

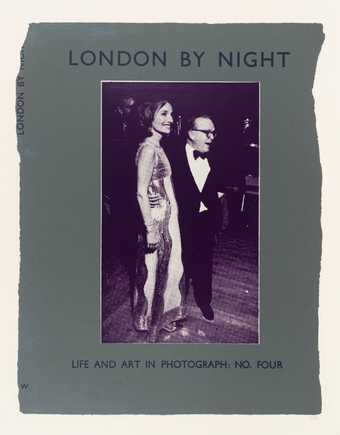

‘It seems uncanny that you detect a South American air because while I was painting the picture (first six months of 1973) I was deeply reading Waterton and Burton and mainly Humboldt’s travel in the Orinoco... I must have been touched some by those wonderful plates you find in those books.

‘It took less time than some other pictures—I painted on it for six months on and off...’

(Where a group of three dots is given this is the artist’s punctuation. Four dots indicates matter excluded from quotation.)

Published in The Tate Gallery Report 1972–1974, London 1975.

Explore

- architecture(30,960)

- domestic(1,795)

- heating and lighting(846)

- calendar(20)