- Artist

- R.B. Kitaj 1932–2007

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 1830 × 1830 mm

frame: 1982 × 1978 × 90 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1985

- Reference

- T04115

Display caption

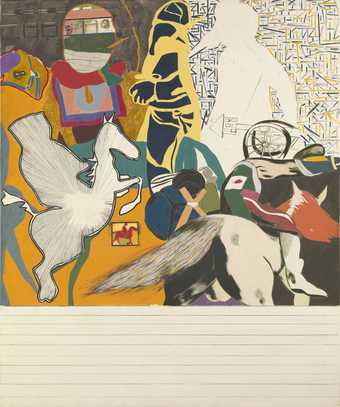

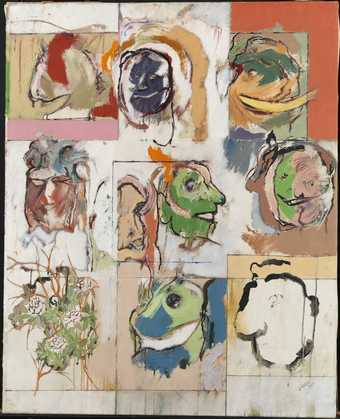

This painting is set in Cecil Court, a street famous for its second-hand bookshops and a favourite haunt of the artist. It is one of many paintings made by Kitaj arising out of an increasing awareness of his own Jewishness. He wrote, 'I have a lot of experience of refugees from Germany and that's how this painting came about. My dad and grandmother ... just barely escaped.' The work shows the artist reclining on a sofa while figures from his life pop out of the street behind him. Kitaj has explained that this theatrical composition was inspired by the peripatetic troupes of the Yiddisher Theatre in Central Europe, which he had learned about from his grandparents and from in the diaries of the writer Franz Kafka.

Gallery label, September 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

R.B. Kitaj born 1932

T04115 Cecil Court, London W.C.2 (The Refugees) 1983-4

Oil on canvas 1830 x 1830 (72 x 72)

Inscribed ‘Kitaj 1983-84' on top bar of stretcher

Purchased from Marlborough Fine Art (Grant-in-Aid) 1985

Exh: The Hard-Won Image, Tate Gallery, July-Sept. 1984 (80, repr. in col.); The British Art Show: Old Allegiances and New Directions 1979-1984, AC tour, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery and Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, Nov.-Dec. 1984, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, Jan.-Feb. 1985, Mappin Art Gallery, Sheffield, March-May 1985, Southampton Art Gallery, May-July 1985 (94, repr.); R.B. Kitaj, Marlborough Fine Art, Nov.-Dec. 1985, Marlborough Gallery, New York, March 1986 (48, repr. in col.); British Art in the Twentieth Century: The Modern Movement, RA, Jan.-April 1987, Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart, May-Aug. 1987 (293, repr. in col.)

Lit: Richard Shone, ‘London, Tate Gallery, The Hard-Won Image', Burlington Magazine, vol.126, Oct. 1984, p.651, pl.49; R.B. Kitaj, ‘Jewish Art - Indictment and Defence: A Personal Testimony', Jewish Chronicle Colour Magazine, 30 Nov. 1984, pp.42-6, repr. p.42; John Russell Taylor, ‘R.B. Kitaj - Marlborough Fine Art', Times, 12 Nov. 1985, p.10; Alistair Hicks, ‘R.B. Kitaj - A Jewish Inheritance', Spectator, 23 Nov. 1985, p.37; Richard Cork, ‘Recovered Identity', Listener, 5 Dec. 1985, pp.40-1; Marco Livingstone, R.B. Kitaj, Oxford, 1985, pp.31-2, 35, 40-1 and 153, repr. pl.143; Marco Livingstone, ‘Kitaj at Marlborough', Burlington Magazine, vol.128, Jan. 1986, p.53; John Russell, ‘Into the Labyrinth of Dreams with Kitaj', New York Times, 16 March 1986, p.36; Andrew Brighton, ‘Conversations with R.B. Kitaj', Art in America, vol.74, June 1986, pp.98-105, repr. p.98 (col.); Donald Kuspit, ‘R.B. Kitaj - Marlborough Gallery', Artforum, vol.24, Summer 1986, p.125; Tate Gallery Report 1984-6, 1986, p.92, repr. (col.); Norman Rosenthal, ‘Three Painters of this Time: Hodgkin, Kitaj and Morley' in British Art in the 20th Century: The Modern Movement, exh. cat., RA, 1987, p.383; Michael Peppiatt, ‘Could There Be a School of London?', Art International, no.1, Autumn 1987, p.9, repr. cover (col.). Also repr: Artforum, vol.24, March 1986, p.13

Kitaj wrote a preface for T04115, which was printed in Livingstone 1985, p.153, and this is quoted in full below. When the artist was asked for further information about T04115, he replied that the source material already available in Livingstone would have to suffice, because he was in the process of writing a fuller piece on the painting, which was due for publication later in 1988. He did not want his new piece to be quoted before it appeared in its proper context.

‘I consider myself no longer a German. I prefer to call myself a Jew'. (Sigmund Freud)

I have very little experience of water-lilies or ballet dancers or jazz or long walks or wine or loneliness. Among some other things, I think I have a lot of experience of refugees from the Germans, and that's how this painting came about. My dad and grandmother Kitaj and quite a few people dear to me just barely escaped. One of the first friends to see this painting (a 75 year old refugee) said the people in it looked meshugge. They were largely cast from the beautiful craziness of Yiddish Theater, which I only knew at second hand from my maternal grandparents, but fell upon in Kafka, who gives over a hundred loving pages of his diaries to a grand passion for these shabby troupes, despised by aesthetes and Hebraists who were revolted by them. Painters are in the business of ‘baking' (a plot device from Y.T.) [Yiddish Theater] pictures whose perpetration may be sparked by unlikely agents of conversion, which in Kafka's case really caused his art to turn when he met these players. Excited, according to my own habits, I began (in Paris, California, N.Y. [New York City], Jerusalem and London), to collect scarce books and pictures about this shadow world, the trail of which has not quite grown cold in my own past life. I would stage some of the syntactical strategies and mysteries and lunacies of Yiddish Theater in a London Refuge, Cecil Court, the book alley I'd prowled all my life in England, which fed so much into my dubious pictures from the shops and their refugee booksellers, especially the late Mr Seligmann (holding flowers at the left) who sold me many art books and prints. Another day I'll tell who the other people in the painting are supposed to be, whether aesthetes find such midrashic gloss and emendation revolting or not. For now, I must confess that I wish I could continue to paint the shopsigns in the spirit of a distinction made by my favorite antisemite, Pound, who said that symbols quickly exhaust their references, while signs renew theirs.

The setting depicted in T04115, that of Cecil Court, London, WC2, is a pedestrian alleyway linking Charing Cross Road with St Martin's Lane. It is lined on both sides mainly with shops selling rare and second-hand books. Kitaj has painted five names above the shops and they read from left to right: ‘Seligman [sic], GORDIN, LWY, KALB, JOE SINGER'. Seligmann is the only name which refers to a shop in Cecil Court during the years 1960, when Kitaj arrived in London, to 1984, the year which marked the completion of T04115. The other names are not those of book sellers in Cecil Court and are personal to the artist. Ernest Seligmann ran an antiquarian bookshop at number 25 Cecil Court until 1977 when it closed down.

Livingstone (1985) describes Kitaj's purpose in painting T04115:

‘Cecil Court, London WC2 (The Refugees)', painted over the winter of 1983/4, was the first major canvas completed by Kitaj upon his return to London from Paris. Conceived in a spirit of competition with Balthus's painting of ‘The Street', on view at that time in Paris as part of the large Balthus retrospective (the two versions of Balthus's ‘La Rue', dated 1929 and 1933, had been known to Kitaj ‘all my life', particularly as the later version was on display at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, during his youth. They are reproduced in Balthus, exhibition catalogue, Centre George Pompidou, Musée national d'art moderne, Paris, 5 November 1983-23 January 1984, cat. nos 2 and 8 respectively. Kitaj visited the exhibition with Sandra Fisher during their brief honeymoon in Paris just before Christmas 1983), Kitaj regards it as his most ambitious painting in recent years (while working on ‘Cecil Court' Kitaj was looking closely at Venetian painting and made repeated visits to the exhibition The Genius of Venice: 1500-1600, which was on view during the winter of 1983-4 at the Royal Academy, London. Pinned to his wall were reproductions of two pictures from the exhibition, Titian's ‘The Flaying of Marsyas' (a major but little-seen late work from an eastern European collection), and ‘The Washing of Feet', a huge painting from Newcastle-upon-Tyne's Cathedral only recently reattributed to Tintoretto; the figure at the far left of the latter supplied Kitaj with a suitable head for his portrait of Seligmann. The two paintings are reproduced in the catalogue of the exhibition (London, 1983), cat. nos 132 and 101 respectively). A reverie on the way in which his own life has been touched by that of refugees from the holocaust, the picture is a compendium of images rich in personal significance: the setting, an alley of specialist and antiquarian bookshops running between Charing Cross Road and St Martin's Lane, which has been one of the artist's constant London haunts; at the far left, Seligmann, one of the refugees who ran an art bookshop there for many years; at the far right, Kitaj's recently deceased step-father [Dr. Walter Kitaj]; behind him, a shop inscribed with the name ‘Joe S', for Joe Singer, the man who almost became Kitaj's stepfather and who as a fictional character has peopled many of his recent pictures; and in the foreground, a self-portrait based on the cover illustration of a pulp novel, the artist dressed in the clothes which he had worn at his recent wedding and seated on a famous chair designed by Le Corbusier (a photograph taken in 1929 of this chair in a setting also designed by Le Corbusier is reproduced in Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson, The International Style, New York 1966, p.127)

Balthus's two versions of ‘La Rue' both depict the same Parisian streets, the short Rue Bourbon-le-Château crossed in the distance by the Rue de Buci, with their multi-coloured shop fronts and awnings, shop signs and street lamps. Because of the absence of any wheeled traffic in Balthus's painting, these two streets appear to be a pedestrian precinct as Cecil Court is in actuality and in T04115. In the 1933 version of the painting Balthus has depicted nine characters including children, workmen and young women, frozen in their actions. Kitaj depicts nine characters in Cecil Court and includes himself in the foreground as the tenth.

Kitaj, in the red jacket, yellow tie and green trousers depicted in T04115, married the painter Sandra Fisher on 15 December 1983 at the Bevis Marks synagogue, London, an event which took place during the period of execution of T04115 and which in some way is celebrated in it. As Livingstone comments ‘Kitaj and his wife could have found no better means of declaring a future together both as Jews and as artists' (1985, p.32). Kitaj wrote about Jewish art and his own place within it in an article published in the Jewish Chronicle:

... I have always felt displaced, as a person, as a painter, as a Jew. The question of Jewish art never interested me until recent years. ... In the life and work and death of [Walter] Benjamin, I found a parable and a real analogue to the very methods and ideas I had pursued in my own painting: a shifting urban complex of film-like fragmentation, an additive, free-verse of an art, collected in the political and cultural urgencies of the diaspora Jew (albeit in his moment of greatest peril and horror).

In the early 1970s I marked that inspiration in two paintings ‘about' Walter Benjamin, ‘The Autumn of Central Paris' and ‘Arcades' [both are reproduced in Livingstone 1985, pl.57 and pl.46]. I guess they were the first stirring of the bloodline, although I had

painted pictures ten years before with some Jewish implication. Benjamin spoke to my sense of exile of mind and heart, an un-at-homeness in great sensual cities which might lead to an art and maybe

even to a Jewishness of Jewish art (p.46).

Kitaj's preoccupation with Jewish themes continues into the 1980s with paintings such as ‘The Jewish School', ‘Rock Garden' (both repr. Livingstone 1985, pl.114 and pl.129) and T04115. Livingstone remarks of these three works that they

all owe a debt, he [Kitaj] says, "to the rediscovery of the world and teaching and destruction (murder) of the Hassidic Zaddikim (magical holy men)". Each of these pictures contains a narrative about the fate of the Jews, their exile and dispersal ... Only "Cecil Court", which treats those whose lives were set off-course, but not destroyed, by anti-semitic persecution, gives much cause for hope (Livingstone 1985, pp.35-6).

Published in:

The Tate Gallery 1984-86: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions Including Supplement to Catalogue of Acquisitions 1982-84, Tate Gallery, London 1988, pp.196-9

Explore

- architecture(30,960)

-

- public and municipal(2,385)

-

- shop(399)

- townscapes / man-made features(21,603)

-

- street(1,623)

- recreational activities(2,836)

-

- reading(400)

- furnishings(3,081)

-

- couch(203)

- book - non-specific(1,954)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- reclining(814)

- Jewish(3,752)

- group(4,227)

- Kitaj, R.B.(8)

- Seligmann(1)

- groups(310)

- individuals: male(1,841)

- self-portraits(888)

- UK countries and regions(24,355)

-

- England(19,202)

- Cecil Court(1)

- government and politics(3,355)

-

- refugee(1,995)

- displacement(24)

- arts and entertainment(7,210)

-

- artist, painter(2,545)

- entertainer(49)

- shopping(100)

- bookseller(5)