- Artist

- Sanja Iveković born 1949

- Medium

- Video, monitor, colour and sound

- Dimensions

- Duration: 9min

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 2008

- Reference

- T12852

Summary

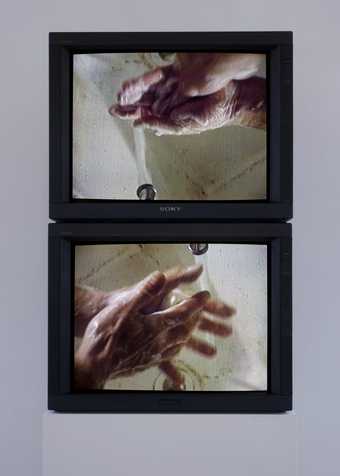

Make-up – Make-down 1978 is a nine-minute colour video by the Croatian artist Sanja Ivekovic. The camera is fixed in a static shot focused on the artist’s upper body, but excluding her head. For the duration of the film the artist applies a number of cosmetic products, but because the artist’s face is never shown we only see her handle the make-up, which she does slowly and deliberately. Ivekovic caresses the cosmetics in an intimate manner: running her hands lovingly over a lotion bottle and a powder jar, stroking the tip of an eyeliner and suggestively turning a lipstick up and down in its case. The video was produced by Galleria del Cavallino in Venice, where an earlier, black and white version of the work had been created in 1976. This 1978 version was originally filmed on an open reel portable video recorder and was later transferred onto a digital betacam tape. It is screened on a monitor.

Make-up – Make-down focuses the viewer’s attention on an ordinary yet private activity, and Ivekovic has described the effect of the work as follows:

Application of make-up is a discreet activity performed between my mirror and myself … The TV-message is received in the isolation of a private space. The everyday movements that I make are slowed down, thereby giving to the ordinary act of applying make-up the character of a ritual performance.’

(Ivekovic in Sanja Ivekovic: Is This My True Face, Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb 1998, p.11.)

In this way the video corresponds with the work of other feminist artists and thinkers who sought to share private experiences with each other. However, it also parallels the feminist critique of the naturalised association between women, femininity and beauty. Ivekovic’s use of video and the television monitor subverts the representation of women in the media by withholding an image of the face. The artist has written that this violates ‘the social-aesthetic contract that links femininity, beauty and desire … [destroying] the entire psycho-social machinery of seduction, persuasion and identity’ (Holert 2008, pp.27–8). Instead of presenting the female body as an object of desire for the male gaze, desire is redirected towards the eroticised cosmetics. It is not the finished image of the woman made-up that is displayed here, but the process or ritual of self-care – of love for oneself – represented by the act of putting on make-up. As such, rather than the camera capturing an image, it acts like a mirror, providing a space for the artist’s self-reflection, in which the viewer is, in turn, invited to share. In this way Make-Up – Make-Down represents a radically different approach to the representation of the female body.

Ivekovic was one of the first women in the former Yugoslavia to identify as a feminist artist, describing it as a ‘gesture of disobedience’ toward the communist perception of feminism as a ‘bourgeois import from the West’ (Ivekovic in Katarzyna Pabijanek, ‘“Women’s House”: Sanja Ivekovic Discusses Recent Projects (Interview)’, Art Margins Online, 20 December 2009, http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/interviews, accessed 7 March 2016). Indeed, Ivekovic’s artistic output and her feminism was profoundly shaped by her experience of the political situation in Yugoslavia. As she stated in 2012:

The important advantage of living and working in socialism is that you learn very early on that nothing is independent from ideology … I have repeatedly asked myself what is my position in the social system, my relationship with the system of power, domination and exploitation, and how can I respond and act meaningfully as an artist … I want to be deliberately active rather than a passive ‘object’ of the ideological system.

(Ivekovic in Roxana Marcoci, ‘Sanja Ivekovic’, Flash Art, March–April 2012, www.flashartonline.com/article/sanja-ivekovic/, accessed 7 March 2016.)

Make-up – Make-down is characteristic of Ivekovic’s feminist-influenced art practice, which is also represented by other works in the Tate collection such as Instructions No. 1 1976 (Tate T12851), in which Ivekovic drew lines and arrows for cosmetic surgery on her skin before smudging the marks into unsightly smears. The series Double Life 1975 (Tate T12969–T12971) comprises photographs of Ivekovic alongside advertisements, highlighting the parallels and distortions between the casual representations of women and the constructed reality of the consumer world. Ivekovic has also made work dealing with the vulnerability of women’s history (see, for instance, Gen. XX 1997–2001) and violence against women (see Turkish Report 2009).

Further reading

Tom Holert, ‘Face-Shifting: Violence and Expression in the Work of Sanja Ivekovic’, in Sanja Ivekovic: Selected Works, Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona 2008, pp.26–38.

Terry Eagleton and Roxana Marcoci (eds.), Sanja Ivekovic: Sweet Violence, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 2011.

Helena Reckitt (ed.), Sanja Ivekovic: Unknown Heroine – A Reader, London 2013.

Philomena Epps

March 2016

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Sanja Ivekovic’s early video works examine the pressures imposed upon women to conform to conventional notions of beauty and explore the feminist contention that ‘the private is the political.’ Ivekovic was the first artist in Croatia to identify herself as a feminist, describing this as ‘a gesture of disobedience toward the communist regime that treated feminism as a bourgeois import from the West’. Ivekovic graduated from art school in 1971, during the period known as the ‘Croatian Spring’, when many Croatian artists rejected the dominance of official, state-sanctioned art.

Gallery label, February 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- objects(23,571)

-

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- lipstick(7)

- government and politics(3,355)

-

- feminism(116)

- conformity(7)

- gender(1,689)

- sexism(137)