- Artist

- John Hoyland 1934–2011

- Medium

- Acrylic paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 2540 × 2540 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1987

- Reference

- T04924

Display caption

Since the mid-1970s Hoyland had given titles to paintings, where previously they had just been dated. Titles were added to identify paintings, not as descriptions of them. ‘Gadal’ is an angel involved in magic rites, and was taken from The Dictionary of Angels (Including the Fallen Angels) by Polish writer Gustav Davidson (published 1971). This book provided Hoyland with a number of titles for paintings in the mid-1980s. At this time, Hoyland introduced circular forms and graphic elements into his paintings. He described this new approach as being ‘more open-ended’.

Gallery label, October 2019

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

T04924 Gadal 10.11.86 1986

Acrylic on canvas 2540 × 2540 (100 × 100)

Inscribed ‘10.11.86 | 100 × 100 | John Hoyland | Gadal’ on back of canvas bottom centre

Purchased from Waddington Galleries (Knapping Fund) 1987

Exh: John Hoyland: Recent Paintings, Waddington Galleries, Feb. 1987 (6, repr. in col.)

Lit:

John McEwen, ‘John Hoyland: New Paintings, 1986’ in John Hoyland: Recent Paintings, exh. cat., Waddington Galleries 1987, pp.3–5, repr. p.17 (col.); Mel Gooding, John Hoyland, 1990, pp.21–2, repr. pl.46 (col.). Also repr: John Hoyland in Conversation with Andrew Graham-Dixon: Radiance Through Colour, 1990, audio-visual pack, slide no.14

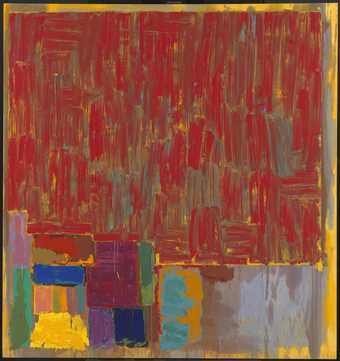

This is one of the more sombre of a series of paintings containing circle motifs, begun by Hoyland in 1983. In a letter to the compiler dated 25 January 1990, the artist described this series as ‘more open-ended than some of my earlier work, where the forms were developed through a more gradual metamorphosis’. T04924 consists of thinly poured layers of paint, built up to form a dark ground on which the artist has placed a black, sprawling, freely painted shape. The edges of the canvas provide evidence of lilac, white, yellow and orange underpainting. In three of the corners Hoyland has introduced more thickly painted circular forms. These are painted in two or more shades of red (top right), yellow (bottom right) and orange (bottom left). This third disc is almost cancelled by a dark swirl of black over-painting. In his letter to the compiler the artist said that T04924 was painted in his studio at Charterhouse Square, London. The painting process involved building up the paint in layers over a number of days, so that each new pouring modified or enhanced the preceding colours. The shapes were then added, in a heavier impasto, which was in turn reworked, so that a resolution between figure and ground was found. Hoyland wrote he did not think that he had made any small related canvases or works on paper ‘except for small drawings which I always make to examine possibilities on a large scale’.

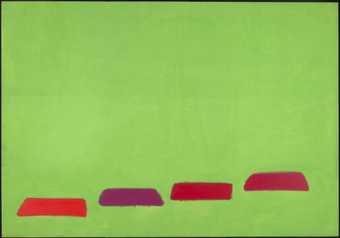

When T04924 was first exhibited, John McEwen wrote in the catalogue that Hoyland's aim in his art ‘has always been the greater liberation of form and colour’. McEwen noted that a pattern had emerged, whereby one series of paintings tended to build up a particular form, while the next broke it down. Out of this fragmentation emerged the new form. He described how the rectangular compositions of the 1970s grew almost to the margins of the canvas, and were then pushed back to the diagonal and were finally fragmented into a series of smaller rectangles. These in turn became less defined and were gradually transformed into triangles which, when broken down, gave birth to the circles of the extended series to which T04924 belongs:

This singular triangle then broke into smaller ones in one of which the circle appeared that was to prove the dominating container of his last show [John Hoyland, Waddington Galleries 1985]. Now, two years on, the external invasion of the circle hinted at in some of those paintings and the revolt of the contained forms have both taken place. The one circle has fragmented into smaller submerged or marginal circles, and from this strife new - invented, non-geometric - forms have flowered; some exotic, others threatening...

He has extended his colour range no less patiently over the years. As he says, nothing is easier than to harmonise colour, but he also has no doubt that colour, more than anything else in a painting, communicates emotion; and not all emotion is harmonious.

(McEwen 1987, pp.3–4).

The first appearance of a circle in Hoyland's painting was in ‘Kilkenny Cats’, 1982 (repr. Gooding 1990, pl.36, in col.). Hoyland (ibid., p.20) said of his gradual transition from compositions based on rectangles to circular imagery in the early 1980s:

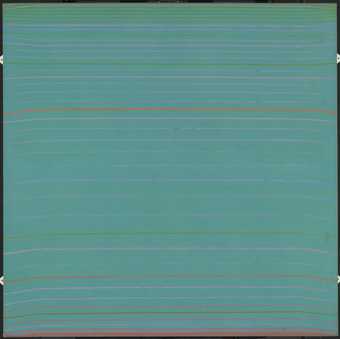

I tried gradually to break from the rectangle and its relationship to the framing edge, and at the same time to bring physicality and tactile feeling to the surface. I worked in a kind of open-ended series, moving from the rectangle to the stressed rectangle and eventually to the dynamic of the diagonal, the form with the greatest potential to suggest movement. This led me to the diamond and the use of the triangle.

Mel Gooding (ibid.) notes Hoyland's awareness of the history of the circle as a motif in modern abstract painting, particularly in relation to American Abstract Expressionism and post-painterly abstraction. Discussing Hoyland's use of circles, he ascribes a range of meanings to the paintings, from ‘the banal to the metaphysical, the comic to the cosmic. These capricious circles ... are visions and nightmares, heavens and hells’.

Hoyland started to give titles to his abstract paintings, rather than indentifying them by date only, in the mid-1970s. He uses titles mainly for easy identification, rather than as clues to his subject matter. Gooding, however, observes that through the 1980s Hoyland's painting became ‘increasingly overt in its reference to its imaginative sources’, and gives a long list of the artist's inspirational sources, ranging from the Avebury Circle, graffiti and musical instruments to food, sex and sunsets (ibid., pp.19, 21).

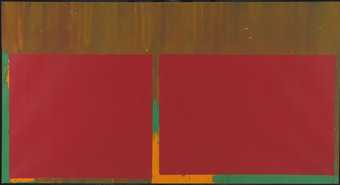

The full title of this painting, ‘Gadal 10.11.86’, includes the date on which it was completed by Hoyland. In his letter to the compiler the artist remarked that while the title of T04924 appeared to fit the image, the painting preceded the title. He wrote that the name ‘Gadal’, meaning an angel involved in magic rites, was taken from The Dictionary of Angels (Including the Fallen Angels) by Gustav Davidson (New York 1971, p.119). This volume has provided Hoyland with a number of titles for recent works, including ‘Zada’, whose central image is a large crimson disc and ‘Quas’, dominated by a yellow mass against a stained green ground, shown with T04924 in John Hoyland: Recent Paintings at the Waddington Galleries in 1987 (repr. pp.7, 9, both in col.). Other paintings titled from the same source include: ‘Helel, Fallen Angel 1.2.88’ (repr. Gooding 1990, pl.52 in col.); ‘Duma 22.2.88’ (repr. ibid., pl.53 in col.); ‘Tagas 2.3.88’ (repr. ibid., pl.54 in col.); ‘Drakon 7.4.88’ (repr. ibid., pl.55 in col., given as ‘Dracon’ in Davison 1971, p.98); ‘Dynamis 24.4.88’ (repr. ibid., pl.56 in col.); ‘Isda 7.12.88’ (repr. ibid., pl.65 in col.); ‘Avatar 1.1.89’ (repr. ibid., pl.67 in col.). A further three closely related paintings, which, like T04924, combine areas of poured paint with more thinly painted disc shapes, are reproduced in the 1987 Waddington catalogue. They are ‘Kumari 28.7.86’ (repr. p.11 in col.), ‘Forest 11.8.86’ (repr. p.13 in col.) and ‘Behind the Arras 18.9.86’ (repr. p.15 in col.). T04924 was the most sombre painting in the Waddington exhibition. ‘Kumari 28.7.86’, described in the catalogue by John McEwen as representing Hoyland ‘at his most ostentatious - it is the sort of painting that wins prizes’, is dominated by a central ‘splash’ of lilac. However, as McEwen notes, the edges of the canvas reveal the multi-layering, ‘the arduous history of its making’ (McEwen 1987, p.4). ‘Forest 11.8.86’ is predominantly orange with partly obscured yellow and blue discs. ‘Behind the Arras 18.9.86’, which as McEwen points out is linked to the earlier ‘Arras’ (repr. John Hoyland: Paintings 1967–1979, exh. cat., Serpentine Gallery 1979, p.26), is a darker, vertical composition of orange, blue, and grey-green, with flashes of yellow.

The artist has approved this entry.

Published in:

Tate Gallery: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1986-88, London 1996

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- colour(2,481)

- gestural(891)

- irregular forms(2,007)