- Artist

- Lubaina Himid CBE RA born 1954

- Medium

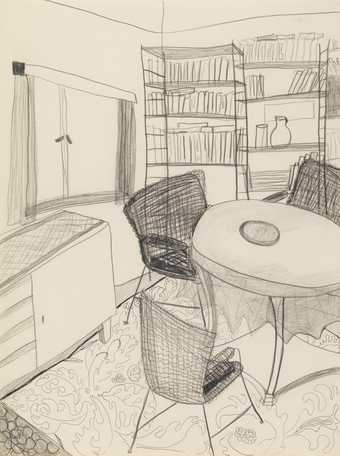

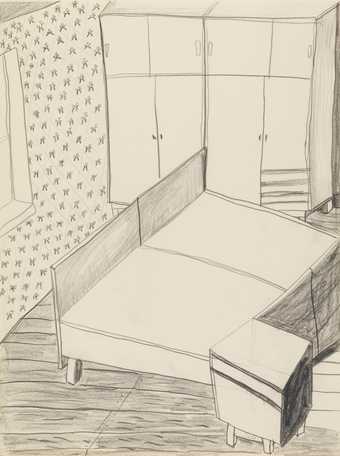

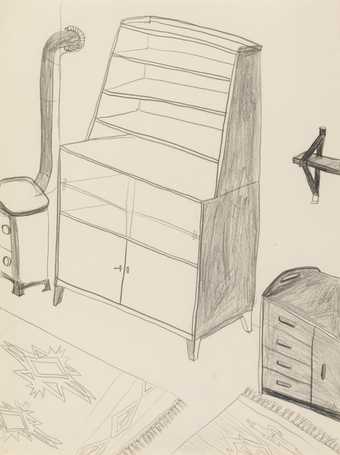

- Wood, textiles, cardboard, paint, graphite, coloured pencil, chalk and ink

- Dimensions

- Object: 2825 × 5780 × 60 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by the Denise Coates Foundation on the occasion of the 2018 centenary of women gaining the right to vote in Britain 2019

- Reference

- T15264

Summary

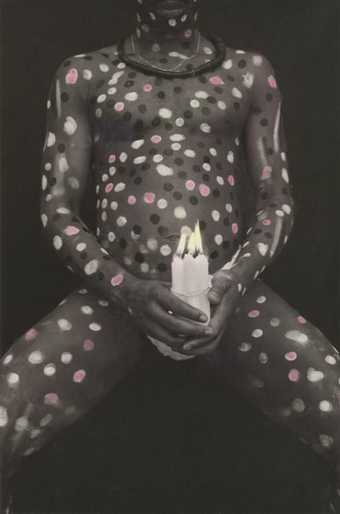

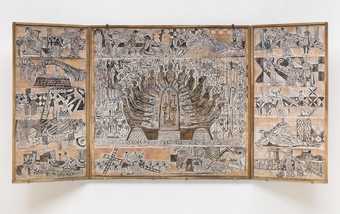

Freedom and Change 1984 is a large installation that has at its centre an image painted onto a pink bed sheet. The sheet is hung against the wall from a rod so that the bottom of the fabric just touches the floor. Additional painted plywood elements to left and right complete the work. The central image depicts two black women dancing or running barefoot across the cloth, holding hands high in the air as if about to twirl joyfully. The women have short cropped hair and are wearing patchwork dresses – one made of various hues of blue, one black and white – created from small torn pieces of cardboard collaged directly onto the fabric, some recognisable as recycled paper tags and envelopes. One woman throws her head back as she kicks her leg up, the other’s gaze is directed ahead. The artist has explained: ‘The device of placing two black women in a painting together was an early method I used to counteract this assumption that there was only one story and that the black woman never spoke’ (Himid 2013, p.93). That Himid’s subjects wear short-cropped hair and Venus symbol ¿ earrings, which during this period would have suggested lesbian identification, also presents the possibility of a romantic relationship between them.

The piece appropriates the painting Two Women Running on the Beach (The Race) 1922 by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973; Musée Picasso, Paris): a small neoclassical image of two white women running in ecstacy along a beach, with white dresses slipping down to expose their breasts. In Himid’s version, these figures are replaced with black women and six additional characters are added: a pack of four snarling black dogs to the right, their leads extending into the space of the central painting where they are held by one of the women, and the heads of two bald white men trapped in the sand to the left. These characters are painted onto plywood which has been cut to size and affixed to the wall at ground level a short distance away from the central panel, so that it appears that the women are kicking sand into the face of the white men. According to critic and curator Gilane Tawadros, Himid’s citation of Picasso, celebrated for his appropriation of African tribal masks, reverses the modernist absorption of ‘primitive art’ and claims ownership of the process of ‘gathering and re-using’ (Tawadros 1989, p.122). The artist explained: ‘“Jazz Age” Paris jumped for joy at the “discovery of Africa and her artifacts and stole them … [but] gathering and re-using has always been part of Black creativity.’ (Himid, quoted in ibid., p.121). Freedom and Change not only challenges the relationship between centre and periphery within modernist discourse, it also creates space to celebrate black women’s subjectivity and their relationships with one another. Such themes have characterised Himid’s work throughout her career. The practice of painting figures and other elements of her compositions on wooden ‘cut-outs’ was typical of her early work and can also be seen in The Carrot Piece 1985 (Tate T14192).

Further reading

Gilane Tawadros, ‘Beyond the Boundary: The work of Three Black Women Artists in Britain’, Third Text, vol.3, issue 8–9, 1989, pp.121–150.

Lubaina Himid, in conversation with Jane Beckett, ‘Diasporic Unwrappings’, in Marion Arnold and Marsha Meskimmon (eds.), Women, The Arts and Globalization: Eccentric Experience, London 2013, pp.190–222.

Jessica Morgan, Burning Down the House, exhibition catalogue, Gwangju Biennale 2014, p.83.

Griselda Pollock, ‘“How the political world crashes in on my personal everyday”: Lubaina Himid’s Conversations and Voices: Towards an Essay about Cotton.com’, Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry, no.43, 2017, pp.18–29.

Laura Castagnini

April 2018

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Lubaina Himid’s large installation is a celebration of relationships between women. Two Black women run barefoot along a beach, holding their hands high in the air as if about to twirl joyfully. Appearing to trample two white men trapped in the sand, they run towards the future, holding the leads of a pack of snarling dogs. Himid wrote about this work: ‘Made on a “theatre curtain”, it precedes the drama and romance of running away ... without depicting the reality of running away or the consciousness of a sudden departure on those left behind.’

Gallery label, August 2020

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.