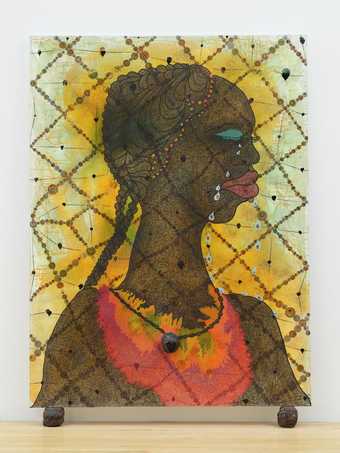

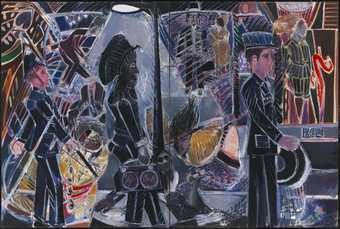

- Artist

- Lubaina Himid CBE RA born 1954

- Medium

- Acrylic paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 1524 × 1219 mm

frame: 1595 × 1293 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the artist 2009

- Reference

- T12885

Summary

Ankledeep 1991 is a large painting by the British artist Lubaina Himid depicting two women standing behind a curving black banner. The banner covers most of the middle sections of the women’s bodies, so that the only parts of them visible are their heads, shoulders, legs, and, in the case of the woman on the right, her left arm. The women, who are both black and have short hair, look away to their left with expressionless faces. The figure on the right drops from her hand small scraps of blue-green paper covered with markings. Behind the women, at the level of their heads and shoulders, is a large block of yellow with horizontal, vertical and diagonal stripes within it in a slightly lighter yellow tone. Above the yellow area is a horizontal section of dark blue, and at the bottom, by the women’s bare legs and feet, are thin strips reminiscent of grass or straw but rendered in white, blue and grey paint.

Ankledeep was completed in 1991 in Preston, where Himid lives and works. It is part of a series entitled Revenge: A Masque in Five Tableaux that the artist finished in 1992 and first exhibited that same year at Rochdale Art Gallery. The series comprises twelve works (ten paintings, an installation and a drawing on paper) that include figurative pieces presenting pairs of black women in a range of scenarios, as is seen in Ankledeep and Between the Two My Heart is Balanced 1991 (Tate T06947), as well as more abstract works suggestive of modernist abstraction and African fabric and textiles, such as Carpet 1992 (Tate T12886). In 1992 Himid made reference to the meaning of the title Ankledeep and the purpose of the scraps featured in the painting: ‘Two women standing ankle-deep behind banners in front of cloths shredding maps; fragments float away’ (Rochdale Art Gallery 1992, p.14), suggesting a connection between the women’s apparent nudity, the fabric that covers them and the maps that they have ripped and discarded. In 2013 the art historian Dorothy Rowe reflected on the nature of ‘revenge’ in the painting, stating that Ankledeep features ‘two black women seeking their revenge from the fabric of history. The women shred and scatter the colonial maps of the past before searching for new robes and debating new directions’ (Rowe 2013, p.306).

The act of destroying maps, which is also depicted in Between the Two My Heart is Balanced, may signify the destruction of forms of knowledge and power that have been the preserve of white men throughout history. Himid has described the intentions and interactions of the women in the Revenge series as follows:

The space they occupy is filled with them and expands with their ideas. They have several strategies, they expand to fill the situation. The women take revenge; their revenge is that they are still here they are still artists, that their creativity is still political and committed to change, to change for the good.

(Quoted in Rochdale Art Gallery 1992, p.32.)

The series may therefore reflect Himid’s reimagining of the role of black women in history, with the activities of her female protagonists forming alternatives to conventional historical narratives.

Himid was born in Zanzibar in Tanzania but moved to England shortly after her birth. Her paintings, woodcuts, installations, works on paper and curatorial projects have frequently explored historical narratives of migration and colonialism, and especially the cultural status of black women. She emerged as a key figure in the development of black British art in the mid-1980s, alongside figures such as Donald Rodney, Keith Piper and Sonia Boyce.

Further reading

Lubaina Himid: Revenge: A Masque in Five Tableaux, exhibition catalogue, Rochdale Art Gallery, Rochdale 1992, reproduced p.36.

Dorothy Rowe, ‘Retrieving, Remapping, and Rewriting Histories of British Art: Lubaina Himid’s Revenge’, in Dana Arnold and David Peters Corbett (eds.), A Companion to British Art: 1600 to the Present, Oxford 2013, pp.289–314.

Eddie Chambers, Black Artists in British Art: A History Since the 1950s, London 2014, pp.128–39.

Richard Martin

September 2014

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

- universal concepts(6,387)

-

- history(1,983)

- politics and society(2,337)

- scientific and measuring(791)

-

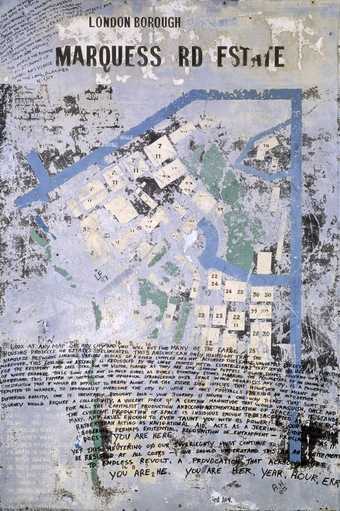

- map(110)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- standing(3,106)

- throwing(15)

- woman(9,110)

- black(796)

- government and politics(3,355)

-

- feminism(116)

- cultural identity(7,943)

- colonialism(429)

- migration(20)