- Artist

- Philip Guston 1913–1980

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 2032 × 2794 mm

frame: 2071 × 2832 × 50 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with assistance from the American Fund for the Tate Gallery 1991

- Reference

- T05870

Summary

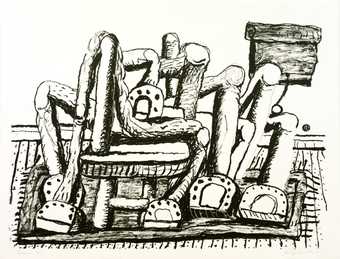

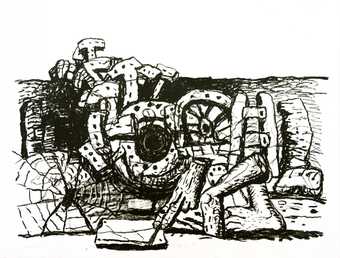

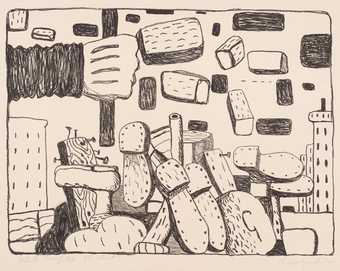

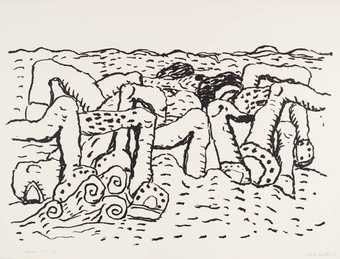

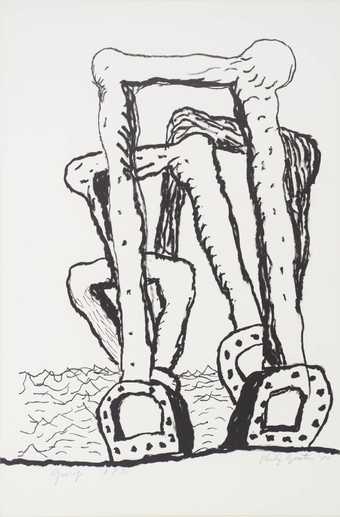

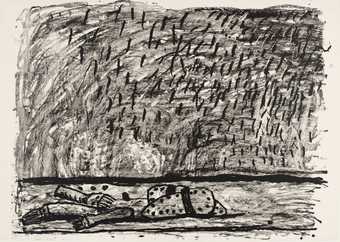

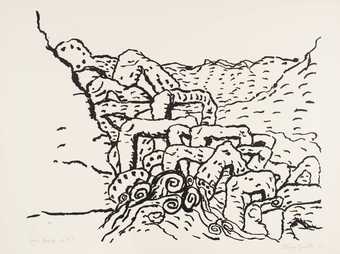

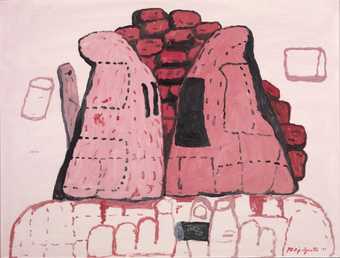

At the centre of this large, even monumental, painting stands a collection of what appear to be disembodied, bent legs. Crossing over each other, these form a flat-topped, loosely assembled mound, painted largely in pinks and reds, that sits on a featureless dark brown landscape, with the horizon’s curving line and a nondescript sky behind. With their crude modelling and emphasised, cartoon-like outlines, the legs are far from realistic. As the novelist and critic Ross Feld, who began a close friendship with Philip Guston in 1976, has pointed out, ‘Some of the legs look as heavy as stone, others like corrugated piping, still others like fleshless casings’ (Ross Feld, ‘Philip Guston’, in Philip Guston, exhibition catalogue, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco 1980, p.28). The legs terminate in oval-shapes that resemble shoes or even horseshoes (upturned towards the viewer, these shapes have rims with repeated dots suggestive of nails). Dark shadows conjure a sense of the scene being illuminated by bright sunshine or, as there appears to be more than one light source, artificial lights.

Monument was painted in the artist’s studio in Woodstock, New York – where Guston had moved from New York City in 1967, and where he would live until his death in 1980 – during the most prolific period in his career, a burst of productivity which began in 1974 and was only curtailed by a heart attack in March 1979. In a letter to the poet Bill Berkson in July 1976, Guston wrote, ‘I’ve been painting around the clock, 24 hours or more – sleep a bit and then go back – it is totally uncontrollable now’ (quoted in Musa Mayer, Night Studio: A Memoir of Philip Guston, New York 1988, p.179). Many of the paintings he produced in this period were, like Monument, large in scale and filled with humorous and paradoxical imagery.

Although Monument’s size – some of the limbs are taller than an adult viewer – reinforces the idea that the painting depicts (and, in itself, might be) a monument, the meaning of the fleshy structure imagined by Guston remains ambiguous, and was never clarified by the artist himself. However, significant personal, historical and artistic sources for these tangled forms can be suggested. When Guston was seventeen, his older brother Nat had his legs crushed in a car accident and subsequently died of gangrene (Mayer 1988, p.17). The pile of limbs in Monument might also provoke thoughts of the Holocaust, an event of persistent interest to Guston (who was Jewish), especially after he saw films of Nazi concentration camps and their victims (Philip Guston, ‘Conversation with Morton Feldman’, in Coolidge 2011, p.80). In this vein, critic Andrew Graham-Dixon has emphasised the commemorative nature of Guston’s work in the mid-1970s, describing Monument and other similar paintings as ‘still lifes composed of dead lives’ (Andrew Graham-Dixon, ‘A Maker of Worlds: The Later Paintings of Philip Guston’, in Auping 2006, p.58). Feld cites a very different inspiration for this painting, claiming that the horse’s legs in Michelangelo’s fresco The Conversion of Saul c.1542–5 (Papal Palace, Vatican City), a work Guston frequently discussed in conversations at the time, are the source of the legs in Monument (Feld 2003, p.102), although the arrangement of muscular human legs in the same painting seem a more obvious source. The suggestion of the feet being twisted and offering impossible views of the soles – a word that conjures its homonym ‘souls’, another link with memory and mourning – can also be seen as echoing the different perspectives in play in Picasso’s late cubist works, including, notably, The Charnel House 1944–5 (Museum of Modern Art, New York).

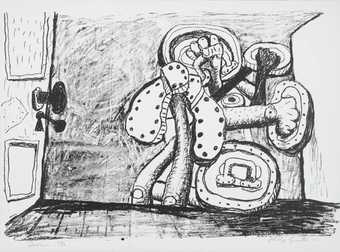

The forms seen in Monument may also be understood in the broader context of Guston’s career. The artist claimed, ‘when I started I wanted to be a cartoonist’ (Philip Guston, ‘Talk at Yale Summer School of Music and Art’, in Coolidge 2011, p.222). However, the figurative paintings Guston displayed from his first solo exhibition in 1931 until the mid-1940s, often imbued with a sense of mystery, were influenced by Picasso and the social realist murals of Diego Rivera. Guston’s early work demonstrated close attention to human legs and piles of debris and objects, in paintings such as Martial Memory 1941 (Saint Louis Art Museum). This style subsequently gave way to a sustained period of abstraction, as Guston became a leading figure in New York’s abstract expressionist scene of the 1950s along with Jackson Pollock, a former school friend of Guston’s in California. From 1968 Guston began to paint everyday items – including books, shoes, light-bulbs and bottles – in a seemingly cruder manner reminiscent of cartoons, a style which was unveiled in a controversial show at the Marlborough Gallery in New York in 1970 and which would dominate the rest of his career. By the mid-1970s, piles of limbs and shoes, as featured in Monument, had become leitmotifs in his work. Similar concerns can be seen in Black Sea 1977 (Tate T03364), where a solitary pink-red form (with black dots suggestive of nails again prominent) sails on a dark sea, and in Green Rug 1976 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), in which a collection of legs are found in a domestic setting.

Monument was first exhibited in 1977 at the David McKee Gallery in New York – the gallery Guston had joined in 1974, having left the Marlborough Gallery two years previously – as part of the exhibition Philip Guston: Paintings 1976. The work was chosen to illustrate the cover of the accompanying catalogue (Philip Guston: Paintings 1976, exhibition catalogue, David McKee Gallery, New York 1977). It was also shown at the prestigious Whitney Biennial in New York in 1978. When Monument was acquired by Tate in 1991, it was part of the first group of purchases and major gifts made through the American Fund for the Tate Gallery.

Further reading

Michael Auping (ed.), Philip Guston: Retrospective, exhibition catalogue, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas 2006.

Ross Feld, Guston in Time: Remembering Philip Guston, New York 2003, p.59, p.102.

Clark Coolidge (ed.), Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations, Berkeley 2011.

Richard Martin

February 2014

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Many of Guston’s paintings have a disturbing quality, featuring abject or grotesque objects. In Monument, legs are grouped in a tangle to form a looming edifice. Guston, who was Jewish, had been deeply affected by film of the Nazi concentration camps, which may have influenced the imagery of disembodied limbs in his work. In 1973, he wrote: ‘Our whole lives (since I can remember) are made up of the most extreme cruelties of holocausts. We are the witnesses of the hell.’

Gallery label, November 2015

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- figure(2,270)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- horror(180)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- shoe(179)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- contorted(76)

- leg(337)