- Artist

- Philip Guston 1913–1980

- Medium

- Oil paint on paper on board

- Dimensions

- Support: 769 × 1017 mm

frame: 776 × 1024 × 41 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the family of Frederick Elias in his memory through the American Federation of Arts 1987

- Reference

- T04885

Display caption

Guston had included sinister images of the Ku Klux Klan in his early murals, one of which was shot at and destroyed by Klan supporters when first shown. In the 1960s he returned to figurative painting and reintroduced the hooded Klansmen to his work. Guston meant his paintings to be interpreted in the light of the political violence of the decade, but he also saw the Klan paintings as ironic self-portraits: 'The idea of evil fascinated me¿I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan. What would it be like to be evil? To plan, to plot.'

Gallery label, August 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

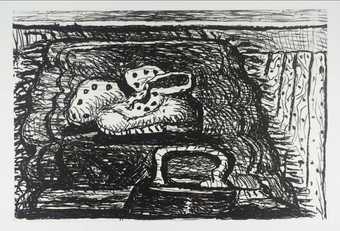

T04885 Cornered 1971

Oil on Strathmore paper laid on board 769 × 1017 (30 1/4 × 40)

Inscribed ‘Philip Guston ‘71’ b.r.; blind stamped ‘Strathmore’

Presented by the family of Frederick Elias in his memory through the American Federation of Arts 1987

Prov: Acquired from the artist by Michael Elias, Burbank, California c.1972–3

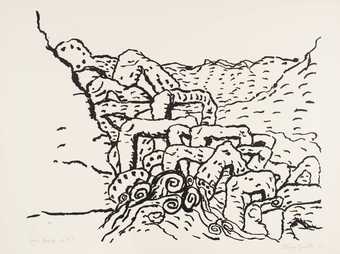

‘Cornered’ depicts two hooded figures facing each other in front of a wall or pile of stones. Behind them, on the left, is an outline cylindrical form, possibly a tin can, a beaker or a mug, and a piece of wood with two protruding nails. On the right is an outline shape of a cup or a mug. Although there are two heads, the two bodies appear to be joined together and are represented as one mass. Consequently, it is difficult to know to whom either of the two hands belongs. The hand on the right holds a cigarette or a cigar and has creases on the middle finger and a finger nail on the index and middle fingers. The hand on the left has no creases and the index finger is raised. The principal motifs are painted in varying shades of pink against a light pink background. The hooded head on the right is painted a darker shade of pink than that on the left, while the bricks are red. A number of the motifs are outlined in black. The cigarette or cigar is black with a grey tip.

In October 1970 Guston took up an appointment as Artist-in-Residence at the American Academy in Rome. In the previous year he had been elected a Trustee of the Academy. He was to spend seven months in Italy where he travelled extensively with his wife, Musa, visiting Florence, Venice, Orvieto and the hill towns of Tuscany, as well as Sicily and Greece. Guston had always had a strong interest in Italian art, especially in the work of Piero della Francesca and Giorgio de Chirico, and had previously been to Italy in 1948. In Rome he was fascinated by the gardens, the Roman remains and the light, and these formed the basis of more than a hundred works on paper which he executed while he was in Italy. T 04885 is one of these.

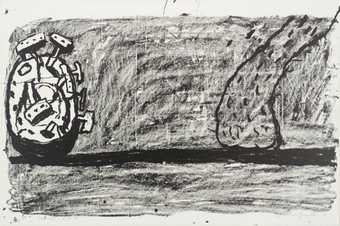

Immediately before going to Italy Guston had a solo exhibition at the Marlborough Gallery, New York, in which he revealed a dramatic change in his recent work. The exhibition had signalled Guston's abandonment of abstraction in favour of a simplified figuration which not only recalled his preoccupations in the early years of his career, particularly in terms of subject matter, but also his participation in 1925 in a correspondence course for cartoonists organised by the Cleveland School of Cartooning. It was his first show of paintings since 1966 when he had exhibited at the Jewish Museum, New York (Philip Guston: Recent Paintings and Drawings, Jan.–Feb. 1966). After this exhibition Guston ceased to paint and concentrated exclusively on drawing. The response to the exhibition had been mixed and Guston himself had begun to question the validity of painting abstractly. The paintings in the Jewish Museum exhibition had contained abstract head shapes (see, for example, ‘Air II’, 1965, repr. Jewish Museum exh. cat., 1966, no.29), which had developed out of the clustered forms of his paintings of the 1950s (see, for example, ‘Painter’, 1959, repr. Philip Guston, exh. cat., San Francisco Museum of Art 1980, pl.31 in col.). The drawings he made after that exhibition consisted of minimal marks, predominantly lines, but gradually his approach shifted and he began to draw recognisable objects such as books, ink bottles and cars in a simplified, cartoon-like manner. In 1970 he described the moment of change as not so much ‘a transition ... when one feeling was fading and a new one had not come into existence’ but as ‘two equally powerful impulses at loggerheads’ (quoted in Robert Storr, Philip Guston, New York 1986, p.47). In a lecture given at the University of Minnesota in March 1978 Guston explained that, ‘The visible world ... is abstract and mysterious enough. I don't think one needs to depart from it in order to make art’ (‘Philip Guston Talking’, Philip Guston: Paintings 1969–80, exh. cat., Whitechapel Art Gallery 1982, p.52). Guston explained, ‘I got sick and tired of all that Purity! Wanted to tell Stories’ (quoted in Bill Berkson, ‘The New Gustons’, Artnews, vol.69, Oct. 1970, p.44). Furthermore, Guston, who by his own admission had been ‘an activist in radical politics’ as a young boy, ‘became very disturbed by the [Vietnam] war and the demonstrations’ and political events of the late 1960s, such as the episodes of violence at the Democratic Convention in Chicago (see Whitechapel Art Gallery exh. cat., 1982, p.52).

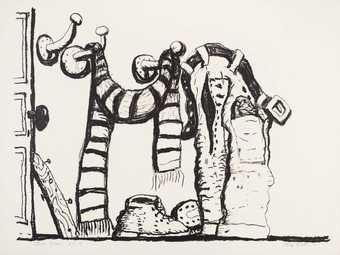

By 1968 Guston had reintroduced into his vocabulary the image of the hooded figure, echoing such early works as ‘The Conspirators’, 1932 (location unknown, repr. Storr 1986, no.6). The hooded figures found in both Guston's early and late paintings referred to members of the Ku Klux Klan who had been powerfully active in Los Angeles where Guston grew up. He recalled in the lecture referred to above that members of the Klan helped the police in strike-breaking, and that some of his paintings based on the notorious racist trial of the Scottsboro Boys had been mutilated in 1931 by members of the police ‘Red Squad’. While Guston's early threatening depictions of the Klan commented upon the rising tide of right-wing extremism, his paintings and drawings of these same characters in the late 1960s and 1970s were humorous, ironic, self-deprecating and consciously anachronistic. Guston aimed to subvert the menace which the depiction of such figures would normally embody. He explained in the Minnesota lecture (quoted in Whitechapel Art Gallery exh. cat., 1982, pp.44–5):

They are self-portraits. I perceive myself as being behind the hood. In the new series of ‘hoods’ my attempt was really not to illustrate, to do pictures of the KKK, as I had done earlier. The idea of evil fascinated me, and rather like Isaac Babel who had joined the Cossacks lived with them and written stories about them, I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan. I was like a movie director. I couldn't wait, I had hundreds of pictures in mind and when I left the studio I would make notes to myself, memos, ‘Put them all around the table, eating, drinking beer’ ... Then I started thinking that in this city, in which creatures or insects had taken over, or were running the world, there were bound to be artists. What would they paint? They would paint each other, or paint self-portraits. I did a whole series in which I made a spoof of the whole art world. I had hoods looking at field paintings, hoods being at art openings, hoods having discussions about colour.

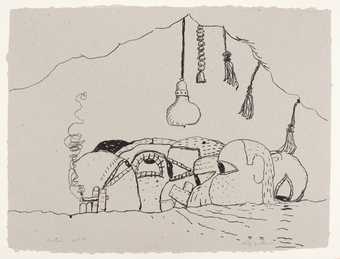

Guston was struck by the fact that these people who commit acts of violence also lead normal lives. To some extent they represent everyman. In lecture notes he prepared in 1977 he wrote: ‘What do they do afterwards? Or before? Smoke, drink, sit around their rooms (light bulbs, furniture, wooden floors), patrol empty streets; dumb, melancholy, guilty, fearful, remorseful, reassuring one another? Why couldn't some be artists and paint one another?’ (quoted in Musa Mayer, Night Studio: A Memoir of Philip Guston by his Daughter, New York 1988, pp.149–50).

The critic Lawrence Alloway described Guston's Klansmen as ‘Ubu-esque’ in reference to Alfred Jarry's play Ubu Roi (1896) (‘Art’, Nation, 30 Nov. 1974, p.574), thereby alluding to their buffoon-like and burlesque qualities. Robert Storr has commented (1986, pp.53–4):

Although Guston plainly took pleasure in the vaudevillian misadventures of his flat-footed desperadoes, the humor in the Klan paintings is less a matter of theatrical stunts than of jarring incongruities. Guston said: ‘When I show these, people laugh and I always wonder what laughter is. I suppose Baudelaire's definition is still valid, it's a collision of two contrary feelings.’

Storr also relates the burlesque character to the notion of the Golem, a human effigy sculpted out of red clay, said to have been made by Cabalistic rabbis at various times from the Middle Ages to the nineteenth century. ‘Considered a re-enactment of the creation of Adam, the fabrication of the Golem was the work of pious men, but as a man-made replica of a divine creation, it was necessarily imperfect. In a culture that prohibited graven images as a usurpation of God's power to make living things, the Golem thus represented both an act of faith and an act of hubris’ (ibid., p.60). According to Storr, ‘Guston's work is more than anything the Golem whose proud, bewildered, and finally horrified progenitor is forced to recognise in his appalling surrogate the image of his own impurity and overwhelming humanity’ (ibid., p.61). In a dialogue with the critic Harold Rosenberg, recorded before Guston's last exhibition of abstract paintings at the Jewish Museum in 1966, Guston stated somewhat prophetically:

I should like the image in my painting to be as puzzling and mysterious to me as if a figure walked into this room and we stopped talking and wondered: Who is he? What is this appearance? We can't fathom why he's here, who he is, what he does, and why he should look the way he looks - as in a story by Kafka, if my memory is correct, when the protagonist comes home, unlocks the door, and there are some beings on the stove. He doesn't know who they are, what they are doing there; they're pulp, they're make-up. He doesn't know what is really going on ... A Golem fascinates me.

(‘Philip Guston's Object. A Dialogue with Harold Rosenberg’, Philip Guston Recent. Paintings and Drawings, exh. cat., Jewish Museum,

New York 1966, [p.12])

In addition to references to the Klan, the art historian Dore Ashton suggests that the hooded figures recall ‘the artists in the scriptoria of the medieval plague years who donnned hooded gowns in the vague hope of avoiding the plague’ (Dore Ashton, Yes, but ...: A Critical Study of Philip Guston, New York 1976, p.156).

Given Guston's acknowledgement that the figure behind the hood is as much himself as an actual Klansman, and in view of the fact that he was a heavy smoker and frequently depicted himself smoking in the late paintings, it may be assumed that the figure on the right holding a cigarette or cigar is the artist himself. The differences between the hands - one creased at the joints and relatively large, the other uncreased and more slender - and between the hoods - the right hood has larger, broader features than that on the left and is of a deeper colour - suggest that the figure on the left may represent Guston's wife Musa. She is the subject of a number of late paintings and acompanied him on his trip to Italy. As such she was his ‘accomplice’.

Guston returned from Italy in the summer of 1971. In his Minnesota lecture he explained that on his return he realised that he ‘had finished with the hoods, they were done, you can't redo a thing once it's done’ (quoted in Whitechapeal Art Gallery exh. cat., 1982, p.53).

Writing about the artistic precedence for the comic brutality of Guston's work in this period, Storr points to the paintings of Max Beckmann and George Grosz, as well as to the work of the Mexican artists Orozco and Posada. According to Magdalena Dabrowski, ‘There are also conceptual affinities to the masks of Ensor, the melancholy Punchinello figures of Tiepolo, Gilles of Watteau, and the characters in Goya's Caprichos’ (The Drawings of Philip Guston, exh. cat., Museum of Modern Art, New York 1988, p.33). De Chirico's mannequin paintings of 1915, such as ‘Le due sorelle’, 1915 (Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, repr. Giorgio de Chirico, exh. cat., Musée national d'art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris 1983, no.35 in col.) may also have influenced Guston's depictions of Klansmen. The eye holes in T.04885 are particularly reminiscent of De Chirico's treatment of the same motif in ‘Le due sorelle’, as is the emphasis on stitching. (Stitching is also to be noted in Guston's early painting ‘The Tormentors’, 1947–8, repr. Storr 1986, no.16 in col.). The placement of the principal motif close to the picture plane, with a deep space beyond, was also a characteristic of the paintings of de Chirico before 1920. Furthermore, the extreme, cartoon-line simplicity of Guston's late drawings, and indeed a number of their motifs such as walls, the sun, monuments and stones are not dissimilar to de Chirico's series of lithographs titled ‘Calligrammes’, 1930 (repr. Paris exh. cat., 1983, nos.127–92). Outside the confines of fine art, Guston's late work was influenced by, or had affinties with, the cartoons of George Herriman, whose Krazy Kat comic strip Guston knew from his youth, and of Robert Crumb, whose work was published in the late 1960s in Zap Comix and other underground journals (for examples of their work and a discussion of their significance to Guston, see Kirk Varnedoe and Adam Gopnik, High and Low: Modern Art & Popular Culture, exh. cat, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1991, pp.169–74 and 214–27). The vocabulary of objects which Guston depicted in his late work can be found in the cartoons of such artists, although it was also derived from Guston's studio or things he saw on his travels.

The motif of a wall occurred in a number of the paintings on paper Guston made while in Italy, and relates to the Roman gardens and Etruscan and Roman excavations which he saw during his seven months abroad. In answers dated 8 March 1989 to questions posed by the cataloguer, Musa Mayer, the artist's daughter, wrote that, ‘The brick wall & ancient stones of this period are almost certainly inspired by Roman ruins’. The depiction of walls also represented a reprise of a significant motif found in such early paintings as ‘Martial Memory’, 1941 and ‘The Conspirators’, 1932 (repr. Storr 1986, nos.11 and 6 respectively), where it is employed to suggest confinement and restriction. The fact that in T 04885 the hooded figures stand in front of this pile of stones or wall suggests that they are in an exterior space. However, the floating presence of the cylindrical form and cup, together with the strip of wood with nail heads contradict this. The location is therefore unspecific, neither interior nor exterior. Musa Mayer suggests that ‘this ambiguity is present throughout the late work - it is another reality which [Guston] creates. The transmutation of objects - cup, mug, cylinder, block, painting etc. is characteristic too. In my view, all interpretations, even contradictory ones, are pertinent’. Cups, mugs and nails are regularly found in the late paintings of Guston.

The predominance of pink in this painting is typical of the series of works now known as the ‘Roma’ paintings (Guston did not title the series himself). When asked whether this pinkness represented Guston's response to the light, possibly the twilight, in Italy and the redness of the earth and stone, or whether it was simply a continuation of the Guston's use of pink in the abstract paintings of the early sixties, Musa Mayer replied ‘all these’. According to David McKee, who worked at Marlborough at the time of Guston's exhibition in 1970 and who subsequently represented Guston when he set up his own gallery shortly afterwards, T04885 was probably one of the early works in the series because ‘it has an American feel. The work became more Roman with changes of landscape and fragments of statues’ (conversation with the cataloguer shortly following the cataloguer's written enquiry of 26 March 1989).

On acquisition the work was known as ‘Cornered’. However, one other drawing of the same year bears the same title (repr. Dabrowski 1988, p.134 in col.). Thus, there is some doubt as to the authenticity of this title. Musa Mayer suggests that the painting should probably be known as ‘Untitled’. She states, ‘It is unlikely that my father would have given the name to both works’. It was generally Guston's practice to inscribe the title on the back of the picture. However, the paper is glued to a board and it is not possible to verify this. Since there is no conclusive proof either way, the title by which the painting was known when presented to the Tate Gallery has been retained.

Frederick Elias, in whose name the painting was presented to the Tate Gallery, was Guston's doctor. Michael Elias stated in response to questions posed by the cataloguer that he had acquired the work directly from the artist.

Published in:

Tate Gallery: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1986-88, London 1996

Explore

- architecture(30,960)

- formal qualities(12,454)

- recreational activities(2,836)

-

- smoking(280)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

- hand(602)

- dress: ceremonial/royal(104)

-

- Ku Klux Klan(1)

- civil rights(183)