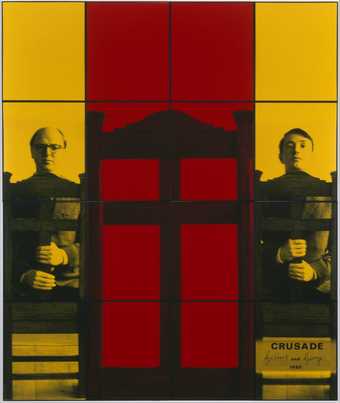

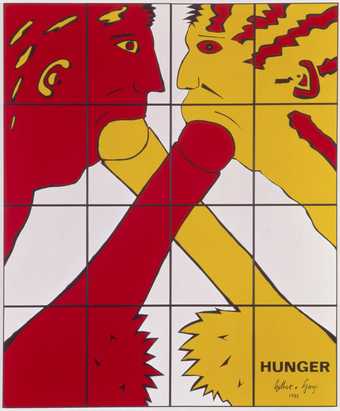

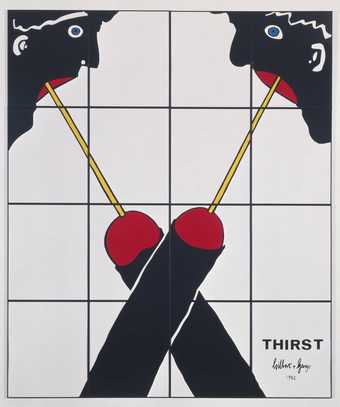

- Artist

- Gilbert & George born 1943, born 1942

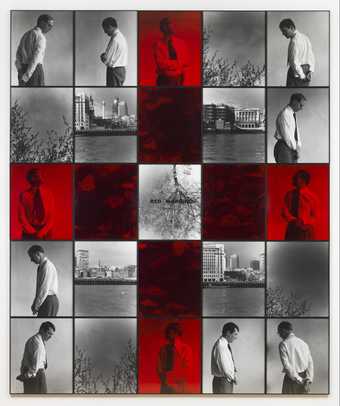

- Medium

- 18 photographs, gelatin silver print on paper with dye on paper mounted onto board

- Dimensions

- Displayed: 2538 × 4260 × 25 mm

- Collection

- ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

- Acquisition

- ARTIST ROOMS Acquired jointly with the National Galleries of Scotland through The d'Offay Donation with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Art Fund 2008

- Reference

- AR00175

Summary

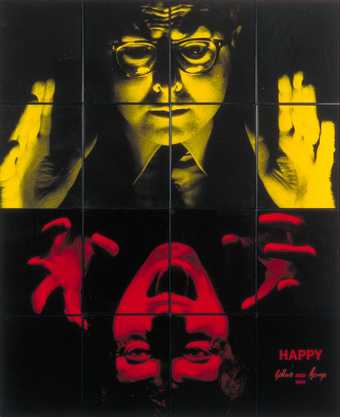

Family Tree is a photographic work by Gilbert & George. It depicts the artists, dressed in suits overlaid in bright purple and red, shown on their hands and knees at the base of a large, dark tree. Instead of fruit, the heads of young men, their faces overlaid in yellow, hang from the branches of the tree. On the artists’ backs miniature likenesses of the artists themselves stand naked, with legs spread. While the smaller Gilbert & George look at one another, the larger, clothed versions look out at the viewer, as do the heads hanging from the branches. The figures and heads appear in front of a blue background patterned by crisscrossing tree branches highlighted in white. The work consists of eighteen individually framed photographs arranged to produce a single image. The thin black frames form a three by six grid across the composition. The title and date of the work, in addition to the artists’ signatures, are printed in the bottom right panel.

The eighteen prints in Family Tree were developed using the gelatin silver process, which produces black and white images. The photographs were printed on resin-coated paper and later hand-coloured before being dry mounted on thin board and framed in black-painted aluminium frames with Perspex glazing. When exhibited, the framed works are hung on horizontal tracks.

Until 1977 Gilbert & George were the only figures depicted in their artworks. When they first began to photograph other people it was from a distance, often through the window of their home on Fournier Street in east London. In 1980, after several years of this covert image-taking, the artists begin to invite strangers to model for them. With the installation of professional photographic equipment in their home studio, the artists began to capture images of youths. In a 1991 interview with writer and broadcaster Daniel Farson, Gilbert explained the importance of photographing these young men from London’s East End:

We want to create a reality that doesn’t exist in art, like the reality of young persons. Many people try to say that the young people in our pictures are all East End boot boys. Many journalists try to say that they’re thugs, hooligans, like the ones in the film A Clockwork Orange [1971] by Stanley Kubrick. But we don’t believe that. We are showing for the first time that a person like that is a total and fantastic being.

(Gilbert in Daniel Farson, Gilbert & George: A Portrait, New York 1999, p.62.)

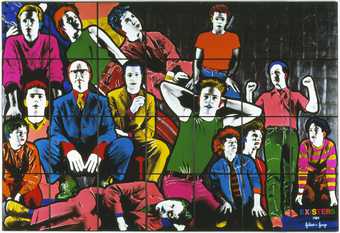

The disembodied heads in Family Tree may well be depictions of such East End boys – a group of people who were previously unrepresented in art. With the title’s allusion to family and the position of the artists at the root, they perhaps go further than this, taking on the role of father figures to these young men. This can also be seen in Existers 1984 (Tate AR00505) in which Gilbert & George surround themselves with young men of varying ages. Art historian Marco Livingstone has argued that the artists have exclusively used male models in their work because the boys are ‘stand-ins for the artists themselves, which is one of the prime reasons that they never use females in their pictures’ (Marco Livingstone, ‘From the Heart’, in Tate Modern 2007, p.22). Livingstone observes that this exclusion has led to misconceptions that their art is misogynistic.

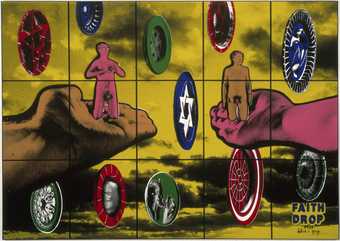

Family Tree was created as a part of the series New Democratic Pictures that was shown at the Anthony d’Offay Galleryin London in 1991. The exhibition shocked viewers as it was the first time Gilbert & George had showed themselves entirely naked (see also Faith Drop 1991, Tate AR00176). Critic David Sylvester’s observation that Gilbert & George were the first artists to show a body as ‘naked’ rather than as a classical ‘nude’ may help to explain why the series was so startling to audiences (see ‘Gilbert & George: Major Exhibition: Room Guide, Room 13’, Tate Modern, London, http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/gilbert-george/gilbert-george-major-exhibition-room-guide/gilbert-11, accessed 3 February 2016). The artists’ removal of their clothing could be seen as a continuation of their stated aim to present an honest account of their vision of life. In a 1981 interview with curator Mark Francis, Gilbert & George explained: ‘We don’t exclude anything, we like the whole. Sometimes we do represent disturbed times … If that is the case’ (‘Gilbert & George: An Interview with Mark Francis’, reproduced in Hans-Ulrich Obrist and Robert Violette (eds.), The Words of Gilbert & George, London 1997, p.115).

Further reading

Jens Erik Sørensen and Anders Kold (eds.), Gilbert & George: New Democratic Pictures, exhibition catalogue, Aarhus Kunstmuseum, Aarhus 1992, reproduced p.51.

Gilbert & George: The Complete Pictures, 1971–2005, London 2007, reproduced p.782.

Gilbert & George: Major Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2007.

Daisy Silver

The University of Edinburgh

March 2016

The University of Edinburgh is a research partner of ARTIST ROOMS.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Family Tree is from the series ‘New Democratic Pictures’. The democracy referred to is one in which each individual is free and encouraged to contribute to society. The change in society proposed by these images is one that is founded on spiritual intoxication and the capacity to dream. Family Tree depicts the artists as colossal figures on their hands and knees at the foot of a large tree. On their backs stand small, naked versions of themselves. They appear to be supporting the tree, nourishing existence at a fundamental level.

Gallery label, February 2010

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- colour(836)

- photographic(4,673)

- universal concepts(6,387)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- suit(301)

- actions: expressive(2,622)

-

- smiling(291)

- man(10,453)

- head / face(2,497)

- Asian(117)

- Gilbert & George(24)

- male(959)

- self-portraits(888)

- birth to death(1,472)

-

- youth(193)

- democracy(23)

- arts and entertainment(7,210)

-

- artist, multi-media(393)