- Artist

- Ibrahim El-Salahi born 1930

- Medium

- Enamel paint and oil paint on cotton

- Dimensions

- Support: 2588 × 2600 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased from the artist with assistance from the Africa Acquisitions Committee, the Middle East North Africa Acquisitions Committee, Tate International Council and Tate Members 2013

- Reference

- T13979

Summary

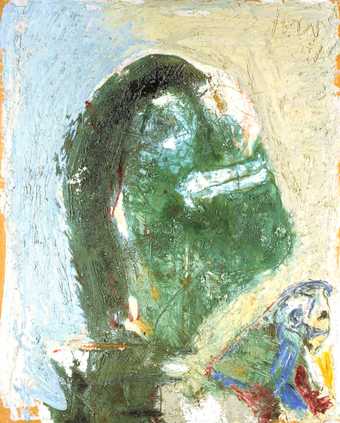

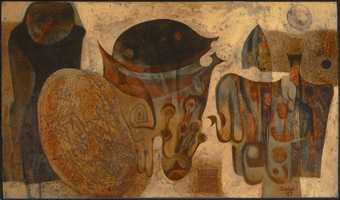

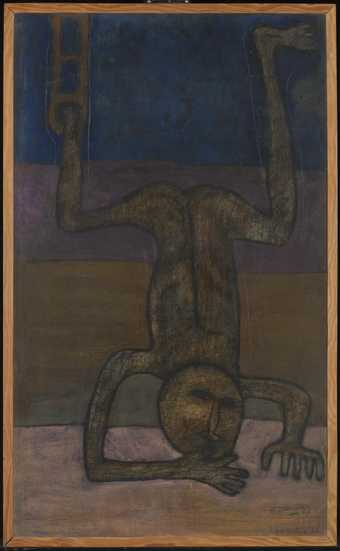

In Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I 1961–5 ghostly figures with stretched heads and hollow eyes emerge from a yellow ground. The figures merge into, and out of, one another. Limbs blend into arabesques and heads are topped with crescents, while white over-painting blurs the distinction between abstract form, pattern and figure. The square format, sober palette, deliberate drips and intentional wrinkling of the paint surface are all characteristic of El-Salahi’s work from this period. While the heads of the figures recall African masks, the artist has also suggested that the ‘elongated, black-eyed, glittering facial shapes might represent the veils our mothers and grandmothers used to wear in public, or the faces of the drummers and tambourine players I had seen circling wildly during funeral ceremonies and chants in praise of Allah’ (Ibrahim El-Salahi, ‘The Artist in His Own Words’, in Hassan 2013, p.84).

Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I is painted in oil and enamel on damouriya, a narrow textile that is hand-woven in Sudan. Three horizontal strips of cloth were stitched together to form a very large sheet of fabric on which El-Salahi sketched his initial composition. He then invited Sudanese poet, painter and filmmaker Hussein Shariffe to work on the middle section of the painting in his studio in Khartoum. The two artists, finding themselves unable to work collaboratively on such a large surface, quickly resolved to cut the fabric vertically into three sections. El-Salahi continued to work extensively on the right panel (which became Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I), initially in Sudan and later in New York, where he travelled in the early 1960s on UNESCO and Rockefeller Foundation Fellowships.

Completed in 1965, this painting was rolled and shipped from New York to Khartoum where it was stored for approximately thirty-five years. During this period El-Salahi established the Ministry of Culture in his native Sudan and played an influential role in developing the country’s cultural policies. However, he was later accused of anti-government activities and imprisoned without trial (see Salah M. Hassan, ‘Prison Notebook: A Visual Memoir’, in Hassan 2013, p.93). On his release El-Salahi chose exile, and has since divided his time between Qatar, the United Kingdom and Sudan. Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I was rediscovered in 2000 and included in El-Salahi’s exhibition at Dara Gallery in Khartoum, his first exhibition in Sudan in more than thirty years (see El-Salahi, ‘The Artist in His Own Words’, in Hassan 2013, p.89). The whereabouts of the smaller left panel completed by El-Salahi and the central panel painted by Shariffe are not currently known.

El-Salahi frequently draws on childhood memories and visions experienced during meditation for inspiration. In his words, he seeks to ‘register and describe what I perceive through the senses while remaining tightly bound to an elusive, indecipherable, metaphysical essence’ (El-Salahi, ‘The Artist in His Own Words’, in Hassan 2013, p.89). In Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I the lines and forms are infused with spirituality and social consciousness. For El-Salahi, sound and line are closely connected. He has explained that lines form letters, which in turn inform sound and thereby enable communication (in conversation with Tate curator Kerryn Greenberg, 24 May 2012). Historian Salah Hassan has noted that El-Salahi ‘was fascinated by the visual spaces created in Arabic calligraphy, whose influence on his work is inextricably interwoven with memories of his childhood and early schooling at the hands of his own father, who ran a Qur’anic school in his house’ (Salah M. Hassan, ‘Ibrahim El-Salahi and the Making of African and Transnational Modernism’, in Hassan 2013, p.21). This connection is explicit in El-Salahi’s title Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I, in which he captures the fleeting, and often dramatic, moments when memory and dreams, past and present, collide. Another work in which El-Salahi combines calligraphy with the painted image is Untitled 1967 (Tate T13736).

El-Salahi is widely regarded as one of the pioneers of modern art in Africa. In Sudan he is credited with developing a new visual vocabulary drawing on traditional Arabic calligraphic forms and religious iconography. After completing his initial studies at the Gordon Memorial College in Khartoum, El-Salahi travelled to London where he studied painting and calligraphy at the Slade School of Art (1954–7), experimenting with Western techniques and styles, but not accepting them uncritically. After graduating, El-Salahi returned to Sudan where he taught for many years and was one of the leaders of a distinct new movement, which came to be known as the Khartoum School (see ‘Ibrahim El-Salahi Interviewed by Ulli Beier’, in Hassan 2013, p.111). While a prominent figure in the Khartoum School, he also played an important role in imagining a broader Africanist aesthetic in the 1960s, engaging with the Mbari Artists and Writers Club in Ibadan in Nigeria and participating in the First World Festival of Black Arts in Senegal in 1966 and Second World African Festival of Arts and Culture in Lagos in 1977.

When El-Salahi returned to Khartoum in 1957, he rapidly realised that the conditions in Sudan, a newly independent country in the throes of the First Sudanese Civil War (1955–72), required a different approach to the colourful gestural portraits and abstract paintings he had been making in London. He recalls: ‘I came to see that … if I was to have a relationship with an audience, I had to examine the Sudanese environment, identify what it offered, assess its potential as an artistic resource, and explore its possibilities as a complementary element in artistic creation’ (El-Salahi, ‘The Artist in His Own Words’, in Hassan 2013, p.84). By the early 1960s El-Salahi’s paintings were comprised of simple forms and strong lines inspired by Arabic and African sensibilities, forms and iconography. He had also reduced his palette to sombre tones (black, white, grey, yellow ochre, burnt sienna and deep red) referencing the colours of the Sudanese landscape.

Further reading

Ulli Beier, ‘The Right to Claim the World: Conversation with Ibrahim El Salahi’, Third Text, vol.7, Summer 1993, pp.23–30.

Salah M. Hassan, ‘The Khartoum and Addis Connections’, in Clementine Deliss (ed.), Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa, Paris and New York 1995, pp.109–25.

Salah M. Hassan (ed.), Ibrahim El-Salahi: A Visionary Modernist, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2013.

Kerryn Greenberg

August 2012

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

El-Salahi studied painting in Khartoum, Sudan, in the late 1940s. He then completed his studies in London. When he returned to Sudan in 1957 it was a newly independent country in the middle of a civil war. El-Salahi recognised that this new context required a different artistic approach. He started using simple forms, strong lines and sombre colours. He was inspired by his environment and included Arabic and African forms and iconography. In this work El-Salahi captures the moments when memory and dreams, past and present collide.

Gallery label, June 2020

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Film and audio

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- figure(2,270)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- memory(367)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- standing(3,106)

- figure(6,809)

- lifestyle and culture(10,247)

-

- cultural identity(7,943)

- inscriptions(6,664)

-

- Arabic text(23)