Ideas Depot

Free- Artist

- Salvador Dalí 1904–1989

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 730 × 921 mm

frame: 1018 × 1205 × 84 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1975

- Reference

- T01979

Display caption

Mountain Lake demonstrates Dalí’s use of the multiple image: the lake can simultaneously be seen as a fish. By such doubling he sought to challenge rationality. The painting combines personal and public references. His parents visited this lake after the death of their first child, also called Salvador. Dalí seems to have been haunted by the death of his namesake brother whom he never knew. The disconnected telephone brings the image into the present by alluding to negotiations between Neville Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister, and Hitler over the German annexation of the Sudetenland in September 1938.

Gallery label, December 2005

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Salvador Dalí 1904–1989

Mountain Lake, also known as Beach with Telephone

1938

Oil paint on canvas

730 x 920 mm

Inscribed ‘Gala Salvador Dalí 1938’ lower left

Purchased from the Edward James Foundation (Grant-in-Aid) 1975

T01979

Ownership history:

Purchased from the artist by Edward James, Chichester; Edward James Foundation (on loan to the Tate Gallery from 1958 until acquired).

Exhibition history:

References:

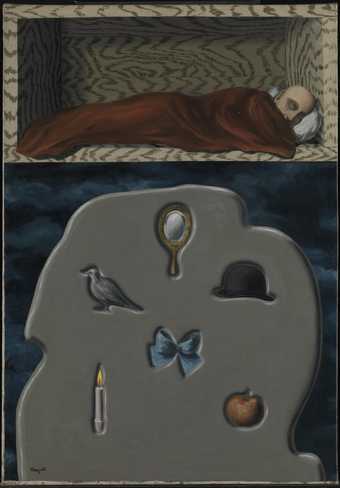

In his painting Mountain Lake Dalí presents the viewer with a visual double-entendre: the silvery lake mentioned in the title, in which the distant mountains are reflected, can also be read as a fish lying on a table, it’s forked tail protruding beyond the left edge. A rock reflected in the surface of the water forms the shape of the fish’s gills. An old-fashioned telephone receiver, resting precariously on a crutch, dominates the foreground of the painting. A snail sits to the left of the suspended telephone. According to the art historian A. Reynolds Morse, the lake depicted here is in the Pyrenees near the Catalonian town of Requesens, and is actually no bigger than a pond: ‘There, after the death of Dalí’s younger brother, Dalí’s father took Mrs Dalí. It was a long trip by wagon up the dry, arid hills. Mrs Dalí was very depressed by the loss of her son, also named Salvador. When they finally reached the “lake” it was so beautiful that she burst into tears, and was relieved of her depression.’1

Dalí executed a number of paintings between 1937 and 1939 that include a French-style telephone similar to that seen in Mountain Lake. This telephone has been widely interpreted as signifying Dalí’s disappointment with then English Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s failed telephone negotiations with Adolf Hitler surrounding the Munich Agreement on 30 September 1938 – an interpretation that relies heavily on the presence of the telephone in the artist’s 1938 painting, The Enigma of Hitler (Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid). However, in his book The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (1942), the artist eschewed such political symbolism in favour of more culinary descriptions: ‘I do not understand why, when I ask for a grilled lobster in a restaurant, I am never served a cooked telephone’, he wrote.

I do not understand why champagne is always chilled and why on the other hand telephones, which are habitually so frightfully warm and disagreeably sticky to the touch, are not also put in silver buckets with crushed ice around them. Telephone frappé, mint-coloured telephone, aphrodisiacal telephone, lobster-telephone … telephones … telephones … telephones.2

Each of Dalí’s telephone paintings – including Mountain Lake – pairs telephones with various foodstuffs: Imperial Violets 1938 (Private Collection), Telephone in a Dish with Three Grilled Sardines at the End of September 1939 (The Salvador Dalí Museum, Florida) and Mountain Lake combine telephones with fish; The Sublime Moment 1938 (Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart) pairs the telephone with fried eggs; and even The Enigma of Hitler includes oysters as well as the telephone. That the telephone features in so many works without conspicuous reference to Hitler or Chamberlain, yet usually in combination with food, may suggest that its significance goes beyond ‘communication’ or ‘telephone diplomacy’.3

The crutch, meanwhile, is a recurring symbol in Dalí’s work and relates to one of his earliest memories of putrefaction. The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí reveals that the crutch’s significance can be traced to a childhood visit to their family friends the Pitchot’s countryside property, ‘El Muli de la Torre’ (The Tower Mill). Early one morning, when exploring the tower’s attic, Dalí discovered a crutch that struck him as ‘being terribly personal and overshadowing everything else’;4 he began brandishing the crutch as a royal sceptre. Shortly afterwards, however, he was exploring the chicken coop when he came upon the remains of his pet hedgehog. The hedgehog had been missing for a week and was now a decaying, hairy mass. Simultaneously compelled and disgusted by his find, Dalí poked the hedgehog with the end of his crutch, unleashing a swarm of gesticulating worms. Frightened by the grotesqueness of the events, Dalí fled, leaving behind his beloved crutch. He returned later to rescue it, though he remained disturbed by its contamination and subsequently dipped the soiled end of the crutch into the mill-stream to ‘purify’ it again. ‘And since then’, Dalí wrote, ‘that anonymous crutch was and will remain for me, till the end of my days, the “symbol of death” and “symbol of resurrection!”’5

The Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí suggests in its online catalogue raisonné that Mountain Lake may have been exhibited in Dalí’s 1939 exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery, New York, under the otherwise unattributed title, Melancholic Eccentricity. This speculation is based on a period photograph of the painting by André Caillet, on the reverse of which is written, ‘Melancholic eccentricity’. The painting’s first confirmed exhibition, as Mountain Lake, was in 1941, though it was subsequently exhibited in 1946 simply as The Lake; since 1970, it also came to be known by the more generic title, Beach Scene with Telephone.

Elliott H. King

December 2007

Supported by The AHRC Research Centre for the Study of Surrealism and its Legacies.

Notes:

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- visual illusion(118)

- universal concepts(6,387)

-

- dysfunction(40)

- menace(209)

- electrical appliances(404)

-

- telephone(147)

- crutch(24)

- countries and continents(17,390)

-

- Spain(349)

- transport: water(8,015)

-

- boat, sailing(3,533)