- Artist

- Ian Breakwell 1943–2005

- Medium

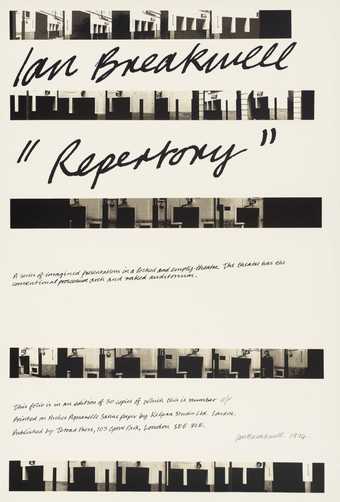

- 11 works on panel, photographs, gelatin silver print on paper, graphite and ink

- Dimensions

- Displayed: 1233 × 6159 × 19 mm

frame 1: 230 × 275 × 19 mm

frame 2: 224 × 282 × 32 mm

frame 3: 1232 × 727 × 19 mm

frame 4: 1232 × 389 × 19 mm

frame 5: 1232 × 953 × 19 mm

frame 6: 1232 × 575 × 19 mm

frame 7: 1232 × 577 × 19 mm

frame 8: 1232 × 1140 × 19 mm

frame 9: 1232 × 388 × 19 mm

frame 10: 1232 × 469 × 19 mm

frame 11: 1232 × 384 × 19 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 2001

- Reference

- T07701

Summary

Breakwell is one of a group of radical British artists who, in the 1960s, challenged the conventional orthodoxy of modernism. The results of this challenge were the ‘dematerialisation’ of the art object from its traditional, commercially marketable format as painting or sculpture and its reconstitution as text, document, photograph or other cheap, reproducible or even insubstantial material. The modernist notion of expressive creativity was rejected and strategies of detachment were adopted. Many artists of this generation used the techniques of the social scientist, documenting their lives or the lives of those around them using photography, recorded notes and journals.

Breakwell began writing a Continuous Diary in 1965. In this document, maintained until 1985, he recorded incidental details of his life including carefully observed moments of absurdity, pathos, incongruity, alienation and mundanity. At the same time he began to create a series of related text, collage and photographic works which constitute individual Diary Pages (see Tate P77032-P77041).

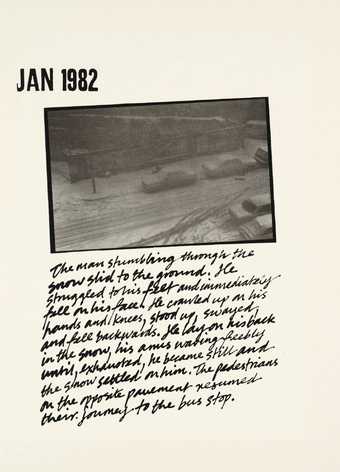

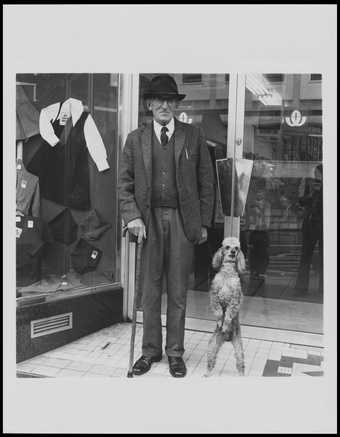

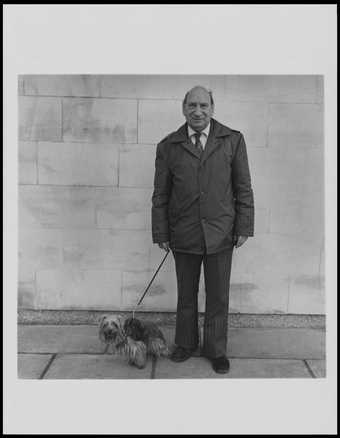

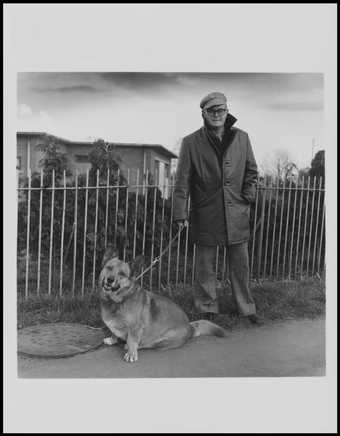

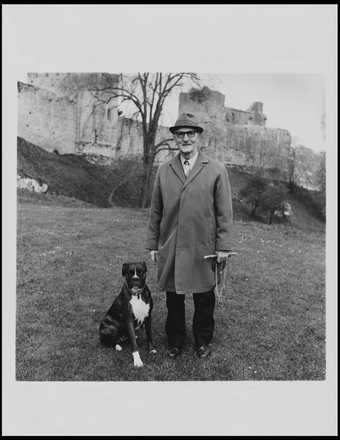

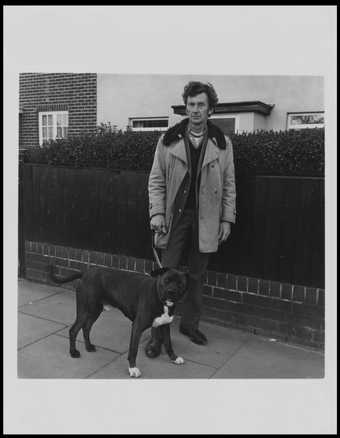

The Walking Man Diary records the repeated appearance of an unknown man walking a regular route around the Smithfield area in the City of London, where Breakwell was living at the time. From the window next to his desk, the artist spent much time gazing out at the scene below. He described how one day, he noticed a man,

just as purposeful as those around him but not engaged in any business except that of walking continuously on a circuitous and regular route around the market area. He had white close-cropped hair and a stubbly beard. He was dressed, whatever the weather, in a long heavy overcoat, thick trousers and boots, but he was not a tramp because he carried no baggage ... Sometimes he would suddenly halt, freeze in one position for perhaps half an hour, then start walking again at the same relentless pace, his head bowed, never looking to either side.

I began to take photographs of him if he happened to be passing by when I looked out of the window. All the photographs are taken from the same third floor window vantage point: the view is the same but the time passes. Two adjoining photographs may be separated by seconds, or weeks, or months.

(Quoted in Ian Breakwell: Continuous Diary and Related Works: Circus, p.25.)

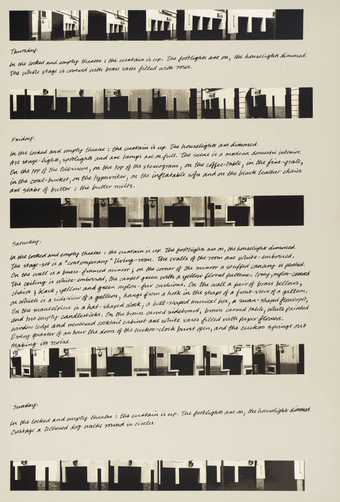

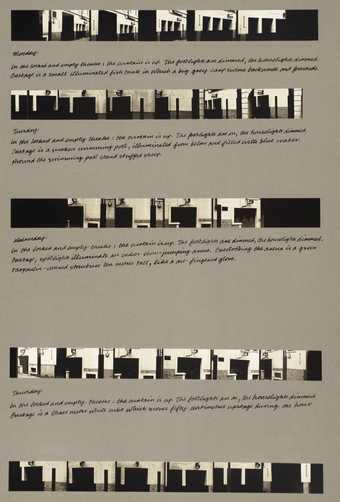

After the man’s sudden disappearance in 1977, Breakwell began making the diary, ‘in retrospect’. A year later, when the man unexpectedly reappeared, the artist photographed him again. He subsequently used photographs taken over a period of three years to make the eleven collage panels of The Walking Man Diary. In addition to photographs of the old man (walking, standing, sleeping or sometimes only his shadow) the collages combine cut-outs from calendars and diaries, photographs of a wristwatch on a wrist, handwritten questions and typewritten fragments of descriptive text. The sense of reportage is heightened by a circle superimposed over the images to isolate and draw attention to the position of the man. The diary records a process of observation which yields frustratingly little real information about its subject. Even where a photograph of the man has been enlarged, it is too grainy to reveal more than a shadowy outline. Breakwell reveals the limitations in the depth of knowledge gained through this kind of looking.

Further reading:

Jeremy Lewison, Ian Breakwell: 120 Days and Acting, Madrid 1983, pp.8-11, reproduced pp.9-10 (detail)

Ian Breakwell: Continuous Diary and Related Works: Circus, exhibition catalogue, Scottish Arts Council Gallery, Edinburgh, Third Eye Centre, Glasgow 1978, pp.6 and 25, reproduced pp.25-9

Live in Your Head: Concept and Experiment in Britain 1965-75, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Gallery, London 2000, pp.50-1

Elizabeth Manchester

May 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

During the 1970s, Ian Breakwell was living in a flat overlooking Smithfield Market in the City of London. From his window, he began to take photographs of an old man he often saw walking around the market below. Although the man appeared to be walking purposefully, he never seemed to be going anywhere in particular.

Although we learn little about the man, Breakwell’s work represents his repetitive, yet seemingly aimless, route through the landscape of the city. This is measured against Breakwell’s static yet habitual recording of the man’s activity through the observational discipline of the diary form.

Gallery label, February 2010

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- architecture(30,960)

-

- townscapes / man-made features(21,603)

-

- street(1,623)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- diary(152)

- photographic(4,673)

- repetition(391)

- reading, writing, printed matter(5,159)

-

- diary(5)

- calendar(20)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- walking(607)

- man, old(373)