- Artist

- Sir Frank Bowling OBE RA born 1934

- Medium

- Acrylic paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 2364 × 1295 × 27 mm

frame: 2413 × 1347 × 45 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by Rachel Scott 2006

- Reference

- T12244

Summary

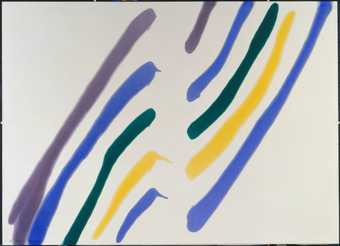

This painting is made up of three vertical strips of green, yellow and red which occupy the left, centre and right of the painting respectively, from top to bottom. Outlines of maps of Guyana and the South American sub-continent have been stenciled in off-white paint on top of these strips in the centre of the canvas. Painted using water-based acrylics, the boundaries between the three strips of contrasting colour are ragged and indistinct. Bowling began using acrylics in the late 1960s because the fast drying nature of the paint allowed for more malleability and the practice of staining created a sense of diffusion between the different tones. As the size of his paintings increased in this period, Bowling moved from upright easel painting to working directly on canvases spread out on the studio floor or pinned to the wall. This allowed him to use broader brush strokes and play with loose overlays and stencils. The outlined maps in this work were produced using readymade stencils which Bowling employed in numerous paintings of the same period, such as Mother’s House on South America 1968. Bowling was influenced by the use of maps in paintings by the American artists Jasper Johns and Larry Rivers, whom he befriended after moving to New York from London in 1967.

Bowling’s reference to Guyana suggests that the work should be understood biographically: Bowling was born there in 1936 and emigrated to Britain in 1950. However, Bowling himself resisted such interpretations and saw his works as examples of the American critic Clement Greenberg’s objective high modernism. By way of the work’s humorous title and through its adoption of the colours of the Guyanese flag, Bowling explored the cultural complexities of an African diasporic identity, playing with the aesthetic objectivity of abstract expressionism and interpretations of his own painting practice as ‘black’. As a contributing editor of Arts Magazine between 1969 and 1972, Bowling wrote a number of articles on this theme, exploring, with a humourous tone comparable to the title of this work, the challenges of being an artist of ‘colour’.

The work’s title alludes to a painting from 1967 by the American abstract expressionist artist Barnett Newman, entitled Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue II (Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart). The thinner yellow strip in Bowling’s painting refers directly to Newman’s compositional ‘zip’ device, a thin line of paint which separated large fields of contrasting colour and provided the flat canvas with a sense of space and depth. Bowling’s spectral outlines of maps, positioned along the ‘zip’ of his own work, add further compositional and interpretive depth to his work in that they seem to challenge the dominance of North American artists in the practice of painterly abstraction. The colloquial naming of ‘Barney’ in the work’s title suggests a playful engagement with Newman’s work, but it also reflects Bowling’s growing concerns with being pigeonholed as a ‘black artist’ by critics and curators.

In its use of maps and the colours, this work exemplifies the transition between figurative painting and complete abstraction in Bowling’s career, but also marks a transitional period in the development of Guyanese independence. The work was painted two years after Guyana achieved independence from Britain and two years prior to its recognition as a Commonwealth republic. As well as relating to the Guyanese flag, the three-part colour scheme also suggests the colours of the Rastafari, with, as art critic Mel Gooding notes, ‘red signifying the blood of martyrs, green the vegetation and natural plenitude of Africa, and gold the wealth of Africa’, though, according to Gooding, ‘Bowling was unaware at this time of this specificity of symbolism’ (Gooding 2011, p.65). The series of paintings with maps, of which Who’s Afraid of Barney Newman is an important component, represents Bowling’s final engagement with figurative imagery. In 1972 the artist abandoned all representational references in his painting and began working in an entirely abstract mode.

Further reading

Mel Gooding, Frank Bowling, London 2011, pp.63–5.

Courtney J. Martin, ‘They’ve All Got Painting: Frank Bowling’s Modernity and the Post-1960 Atlantic’, in Tanya Barson and Peter Gorschlütter (eds.), Afro Modern: Journeys through the Black Atlantic, exhibition catalogue, Tate Liverpool, Liverpool 2010, p.53.

Fiona Anderson

September 2013

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Shortly after moving to New York in 1966, Bowling created a series of paintings consisting of flat areas of saturated colour. The works are reminiscent of other American colour field painting of that time. Here Bowling explicitly references one such painter, Barnett Newman and his work Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue II (1967). However, unlike other colour field artists, many of Bowling’s works include stenciled outlines of continents – here, South America, with Guyana enlarged and hovering over it. The series became known as Bowling’s ’map paintings’.

Gallery label, January 2022

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- colour(2,481)

- universal concepts(6,387)

-

- humour(1,441)

- map(110)

- countries and continents(17,390)

-

- America, South(28)

- religions(181)