- Artist

- Sir Frank Bowling OBE RA born 1934

- Medium

- Acrylic paint and spray paint on 2 canvases

- Dimensions

- Displayed: 2748 × 4920 mm

- Collection

- Lent from a private collection 2020

On long term loan - Reference

- L04355

Summary

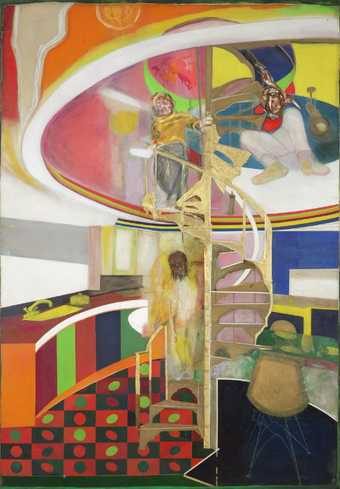

Dog Daze 1971 is a large painting, nearly five metres in width, executed in acrylic and spray paint over two canvases that are stretched separately and displayed abutting each other. The canvas to the left is wider than that on the right. The dominant colours are hues of red, yellow and orange, while a darker, irregular stripe in browns dominates the right-hand edge of the work. The composition is loosely divided into two horizontal bands, the top part being predominantly painted in reds, and the bottom half in yellows and oranges. The left-hand side of the work, across these two halves, is dominated by the outline of the continent of Africa. This continental form is contained and framed by a rectangular shape, its perimeter outlined with spray paint. In the right hand-side of the composition, the outline of Australia is also visible, the continental form being painted in slightly darker yellows than the surrounding area, in the bottom part of the canvas. Other forms suggest aerial views of coastal areas but are not readily recognisable as the outlines of any specific continent or country. Heavily diluted paint is applied in layers across the canvas, in a non-uniform manner. In many areas, red paint poured on the top half of the work has been allowed to run down the canvas in rivulets. Green spray paint has also been used to highlight the bottom part of the outline of Africa and the outline of another irregular form on the right-hand side.

The work was initially painted on one large canvas and was titled Dog Days (the artist in conversation with Tate curator Elena Crippa, 17 October 2019). In 2000 Bowling was invited to exhibit his work as part of the group exhibition 19th & 20th Century: African American Art at Kenkeleba Gallery, New York, curated by Jo Overstreet and Corrine Jennings, funders of Kenkeleba. The gallery space was too small to accommodate Dog Days and Bowling cut the painting into two sections in order to include the larger, left part of the work in the group exhibition. On that occasion, the artist also changed the title of the work to Dog Daze. He has commented that the new title obliquely referred to the stressful experience of exhibiting the work and the pressure he felt put under. The two parts of Dog Daze were stretched separately and displayed together again when the work was exhibited as part of Frank Bowling, Mappa Mundi at Haus der Kunst, Munich in 2017. Other works by the artist, such as Australia to Africa 1971, are also divided into two canvases, stretched separately and displayed abutting each other.

The proportions of the two parts of the work closely approximate that of the Golden Ratio. Since the early 1960s Bowling had studied closely, and loosely applied, mathematical formula to his painting, particularly the Fibonacci Sequence, which is intimately connected with the Golden Ratio. This was the case with the geometry underpinning one of his most ambitious earlier paintings, Mirror 1964–6, also in Tate’s collection (Tate T13936). Additionally, in Dog Daze, as in other works from the time, Bowling used the root rectangle derived from the dimensions of the canvas to establish the positioning of the map stencils.

The work was painted in New York during one of Bowling’s most iconic phases when, between 1970 and 1971, he produced increasingly ambitious large paintings, working with highly dilute acrylic paint and spray paint while continuing to incorporate the outline of continents, particularly South America and Africa. The carefully studied nature of the composition contrasts with the techniques adopted for the application of the acrylic paint. Since acquiring a large studio in SoHo, New York in 1967, Bowling started working on the floor, spreading and pouring diluted colour onto unstretched canvases laid on a wooden purpose-built platform. Moving the canvas between the floor and the wall, he applied paint by staining, pouring and spraying. The images of continental forms were created by gluing a stencil to the canvas and spraying their outline, bleeding spray paint into the fabric of the canvas. In Bowling’s work the building-up of layers of paint is often accompanied by different strategies of erasure. For example, continental forms are at times prominent, at other times submerged into the pools of diluted acrylic paint and rubbed off, so that they nearly disappear.

As Bowling mixed the acrylic paint with copious amounts of water, the wooden platform, made of planks, would allow the excess liquid to drain off. Having absorbed water, the wooden planks would also bend and expand haphazardly, accidentally dictating aspects of the development of the work. In an interview from 1971, at the time of the making of Dog Daze, Bowling said: ‘I think paint as material opposes the rigidity of canvas and its support in such a way that it tends to undermine the entire thing, so that one has to sustain the efficacy of canvas in his contradictory medium.’ (Quoted in Whitney Museum of American Art 1971, n.p.) In the same interview, Bowling stated that colour played ‘an enormous part in my work, if not the most important part’. He went on to explain that, although he would set out to work on a painting with a planned structure, colour ‘remained a very personal dilemma’, as he would make choices about colour following ‘emotional leads’ (Quoted in Whitney Museum of American Art 1971, n.p.).

Bowling started using maps after having moved to New York in 1966. For him, this was a time of personal engagement in discussions condemning the exclusion of non-white artists from American art institutions (see Martin 2019, pp.31–2). Through his writing in Arts Magazine (1969–72), Bowling played a key role in debates around ‘Black Art’. He championed the rights of artists to engage in any form of artistic expression, irrespective of their identity or background. For Bowling, maps were both a compositional device used to organise colour and shapes on the canvas, and a real thing – representing the vast mass of a continent. Maps enabled him to address his own identity as shaped by racism, geo-politics and displacement at a time of great turmoil and change, as many former colonies, including his native Guyana (then British Guiana), had been gaining political independence.

Further reading

Frank Bowling interviewed by Robert Doty, in Frank Bowling, exhibition catalogue, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York 1971, n.p.

Dennis De Caires, ‘In Search of an El Dorado: The Paintings of Frank Bowling’, Artscribe International, no.57, April–May 1986, pp.44–45.

Courtney J. Martin, ‘Social, Material, Otherness: Bowling’s Map Paintings 1966–71’, in Elena Crippa (ed.), Frank Bowling, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2019, pp.29–36.

Elena Crippa

October 2019

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.