Sorry, copyright restrictions prevent us from showing this object here

- Artist

- Louise Bourgeois 1911–2010

- Medium

- Aquatint, drypoint and engraving on paper, triptych

- Dimensions

- Overall: 800 × 3115 × 38 mm

frame each - centre panel: 800 × 1157 × 38 mm

frame, each - left panel: 800 × 912 × 38 mm

frame, each - right panel: 800 × 1046 × 38 mm - Collection

- ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by the Tate Americas Foundation for the Tate Gallery, courtesy of The Easton Foundation 2013

On long term loan - Reference

- AL00349

Summary

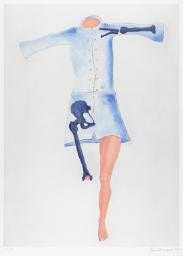

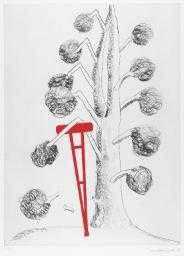

This work consists of three panels that each depict a pair of nude male and female figures whose bodies interact and contort in unusual poses. The left and right panels are mirrored compositionally, sharing a dark blue background, with the left panel depicting a female figure holding onto the waist of a writhing male and the right panel depicting a male figure holding a female. The male and female figures in the central panel are the only pair that are not in direct contact and, unlike the side panels, are presented against a light blue background. Only the torso and legs of the male figures in the central and right panels are visible. The bodies of each of the three female figures adopt similar positions, arched backwards and to the left. Each of the figures appears open-mouthed and wide-eyed. Their bodies are in part skeletal and their faces and sexual organs are rendered simplistically.

This triptych was created to accompany a pair of room installations titled The Red Rooms 1994 (reproduced in Morris 2007, pp.236–41), which are examples of what Bourgeois called her ‘cells’, created by combining salvaged architectural material, found objects and the artist’s own sculptural works. Curator Lucy Askew has noted that the term ‘cell’ has multiple connotations and ‘might suggest the spaces inhabited by monks as a site for prayer and contemplation, but it is also the place where criminals are imprisoned as well as the microscopic elements of the human body and biological matter’ (Askew and d’Offay 2013, p.32). The ambiguity of the cells has a bearing on Triptych for the Red Room, which can be understood to depict scenes of fear and pain or of sexual release. The format of the triptych also instils the work with pseudo-religious and ritualistic overtones.

One figure in each panel adopts an arc-shaped pose, which may serve as a visual shorthand for hysteria, a condition which fascinated Bourgeois. Hysteria was, historically, thought to solely effect women and to derive from problems in the uterus and became a subject of particular interest to psychoanalysts such as Sigmund Freud, forming the basis for some of his writing. The curator Marie-Laure Bernadac has noted that Bourgeois’s relationship with psychoanalysis was always ambiguous as she rejected much of Freudian theory while accepting the importance of the subconscious. Bernadac has also written that, countering traditional psychoanalytic theory, Bourgeois did not see hysteria as exclusively feminine, which is why male figures appear in works such as Arch of Hysteria 1993 (reproduced in Morris 2007, p.43) and in Triptych for the Red Rooms. Bernadac also argued that Bourgeois did not consider hysteria to be an entirely negative or painful experience, and cited Bourgeois herself, who remarked:

Her arch – the mounting of tension and the release of tension – is sexual. It is a substitute for orgasm, with no access to sex. She creates her own world and is very happy. Nowhere is it written that a person in these states is suffering. She functions in a self-made cell, where the rules of unhappiness or stress are unknown to us.

(Quoted in Morris 2007, p.158.)

The figures in Triptych for the Red Rooms resemble those in Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion c.1944 (Tate N06171) in that they arch and twist in similar ways, forming unusual shapes. They are also all depicted with their mouths agape, exposing their teeth either in pain or ecstasy. Curator Frances Morris has noted the similarities between Bourgeois and Bacon: ‘Both worked on the fringes of Surrealism but made highly distinctive bodies of work at a distance from the various avant-garde groupings we associate with modernist art history’ (Morris 2007, p.52). Bourgeois greatly admired the work of Bacon and was introduced to him by the critic and curator David Sylvester in 1951. Afterwards she described the event as ‘an encounter with the man that I have long believed to be one of the greatest painters of our time’ (quoted in Morris 2007, p.52). On the subject of his often contorted male figures, Bourgeois said: ‘He is a painter of terrific brutality. It is a violence that is inflicted on the other and on the self. Bacon was a masochist. He twisted his figures, which were mostly male, like a pretzel into a Möbius strip of attraction and repulsion’ (quoted in Morris 2007, p.53).

Further reading

Mignon Nixon, Fantastic Reality: Louise Bourgeois and a Story of Modern Art, Cambridge, Massachusetts 2005.

Frances Morris (ed.), Louise Bourgeois, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2007.

Lucy Askew and Anthony d’Offay, Louise Bourgeois: A Woman Without Secrets, exhibition catalogue, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh 2013, pp.44, 83, reproduced pp.44–5.

Allan Madden

The University of Edinburgh

November 2014

The University of Edinburgh is a research partner of ARTIST ROOMS.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.