- Artist

- William Blake 1757–1827

- Medium

- Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

- Dimensions

- Support: 460 × 600 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

- Reference

- N05058

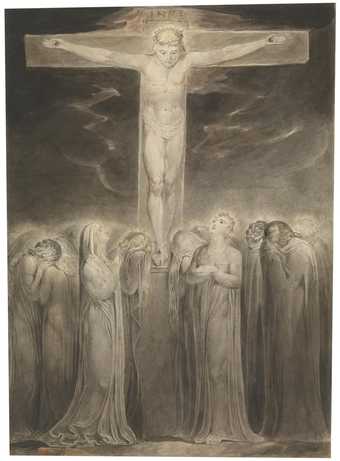

Display caption

Here, Blake satirises the 17th-century mathematician Isaac Newton. Portrayed as a muscular youth, Newton seems to be underwater, sitting on a rock covered with colourful coral and lichen. He crouches over a diagram, measuring it with a compass. Blake believed that Newton’s scientific approach to the world was too reductive. Here he implies Newton is so fixated on his calculations that he is blind to the world around him. This is one of only 12 large colour prints Blake made. He seems to have used an experimental hybrid of printing, drawing, and painting.

Gallery label, October 2023

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

N05058 Newton 1795/c. 1805

N 05058 / B 306

Colour print finished in ink and watercolour 460×600 (18 1/2×23 1/2) on paper approx. 545×760 (21 1/2×30)

Signed ‘1795 WB inv [in monogram]’ b.r. and inscribed ‘Newton’ below design Watermarked ‘JWHATMAN/1804’

Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

PROVENANCE Thomas Butts; Thomas Butts jun.; Capt. F.J. Butts; his widow, sold 2 June 1905 to W. Graham Robertson

EXHIBITED BFAC 1876 (172); Carfax 1906 (29); Tate Gallery 1913 (63); on loan to Tate Gallery 1923–7; BFAC 1927 (54, pl.40); Wartime Acquisitions National Gallery 1942 (11, repr.); Paris, Antwerp (pl.25), Zurich (repr.) and Tate Gallery (repr.) 1947 (36); Romantic Movement Arts Council 1959 (612); Paris 1972 (14, repr.): Hamburg and Frankfurt 1975 (61, repr.); Tate Gallery 1978 (92, repr.); New Haven and Toronto 1982–3 (56b, colour pl.VI)

LITERATURE Gilchrist 1863, 1, pp.375–6; Rossetti 1863, p.203 no.22, and 1880, p.210 no.24; Robertson in Gilchrist 1907, pp.407–8, repr. facing p.396; Blunt in Warburg Journal, 11, 1938, p.61, pl.11a (reprinted in Essick 1973, pp.84–5, pl.29); Saxl and Wittkower 1948, at pl.67, repr. no.6; Preston 1952, pp.53–6 no.10, pl.10; Digby 1957, pp.44–5, pl.45; Martin K. Nurmi, ‘Blake's “Ancient of Days” and Motte's Frontispiece to Newton's Principia’, Pinto 1957, pp.207–16; Blunt 1959, pp.35, 60, pl.30c; Paul Miner, ‘The Polyp as a Symbol in the Poetry of William Blake’, Studies in Literature and Language, University of Texas, 11, 1960, pp.198–205; Damon 1965, pp.91, 298–9; Beer 1968, pp.191, 257, pl.48; Keynes Letters 1968, p.118; Raine 1968, 11, pp.64–5, 136, pl.159; Bentley Blake Records 1969, p.573; Kostelanctz in Rosenfeld 1969, p.126; Robert N. Essick, ‘Blake's Newton’, Blake Studies, 111, 1971, pp.149–62, pl.1; Gage in Warburg Journal, XXXIV, 1971, pp.372–7, pl.66b; Helmstadter in Blake Studies, V, 1972–3, p.108; Donald Ault, Visionary Physics: Blake's Response to Newton, 1974, pp.2–4, repr. as frontispiece; Mellor 1974, pp.97, 155–7, pl.41; Bindman 1977, pp.98, 100, pl.82; Klonsky 1977, p.62, repr. in colour; Bindman Graphic Works 1978, no.336, repr.; Mitchell 1978, pp.49, 51–2, 63, 73; Paley 1978, p.37, pl.30; Essick Printmaker 1980, pp.132, 148, pl.148; La Belle in Blake, XIV, 1980–1, pp.77–81, pl.17; Butlin 1981, pp.166–7 no.306, colour pl.394; Butlin in Blake, XV, 1981–2, pp.101–3, repr.; Bindman 1982, p.55, colour pl.VI; Morton Paley, review of 1982–3 exhibition, Burlington Magazine, CXXIV, 1982, pp.789–90; Bindman in Blake, XVI, 1982–3, pp.224–5; Essick in Blake, XVI, 1982–3, pp.35–6; Ruth E. Fine, review of 1982–3 exhibition, Blake, XVI, 1982–3, p.228; Behrendt 1983, pp.169–70; W.J.T. Mitchell, ‘Metamorphoses of the Vortex: Hogarth, Turner, and Blake’, Richard Wendorf, ed., Articulate Images: The Sister Arts from Hogarth to Tennyson 983; Warner 1984, p.102; Hoagwood 1985, p.69; Baine 1986, p.127, pl.57; Boime 1987, pp.352–5, pl.4.49; Also repr:Figgis 1925, p.75; Mizue, no.812, 1973, ⅔, p.13, colour pl.2

Listed in Blake's account with Thomas Butts of 3 March 1806, apparently as having been delivered on 7 September 1805, as is the probable companion ‘Nebuchadnezzar’. The only other known copy of this print, formerly in the collection of Mrs William T. Tonner, now belongs to the Lutheran Church in America, Glen Foerd at Torresdale, Philadelphia (Butlin 1981, no.307, pl.408). Before the discovery of the 1804 watermark I had assumed that the Tate Gallery copy of the design was the first to be pulled. However, unlike ‘Nebuchadnezzar’, where the character of all three known copies is very similar, the Glen Foerd copy of ‘Newton’ is very different, being closer to the Tate Gallery copies of ‘Pity’ and ‘Hecate’, nos.30 and 31. It therefore seems more likely that the Glen Foerd copy was executed in or about 1795, as indeed was suggested by David Bindman in the catalogue of the exhibition held at New Haven and Toronto 1982–3, when both versions were exhibited (the Glen Foerd version as no.56a, repr.). As Bindman points out, the form of signature on the Glen Foerd copy, ‘Fresco WBlake inv’, corresponds to the version of ‘God Judging Adam’ in the Metropolitan Museum (see no.26) which seems to be the first pull of that composition and again is likely to have been executed in or around 1795; this is so despite the fact that this form of signature is not known to have been used by Blake before 1810, in Butlin nos.667 and 669, and would therefore have been added at a later date, when the print was finished in pen and watercolour for a prospective client. (Morton Paley, in his review of the New Haven, Toronto exhibition of 1982–3, reports a suggestion that the Tate Gallery's ‘Newton’ was not colour printed at all but executed entirely in ink and watercolour, but further examination during the exhibition showed this to be unfounded.)

A pencil sketch in reverse is in the Keynes Collection, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (Butlin no.308, pl.409).

The figure of Newton is related to Michelangelo's Abias, one of the Ancestors of Christ in the lunettes of the Sistine Chapel; Blake had made a copy of this c.1785 from an engraving by Adamo Ghisi (Butlin no.168 verso, pl.207; the engraving is repr. Blunt 1959, pl.30a). The design was also developed from plate 10 of the second issue of There is no Natural Religion of c.1788, which shows an old man kneeling on the ground and drawing with a pair of compasses to illustrate the text ‘Application. He who sees the Infinite in all things sees God. He who sees the Ratio only sees himself only’. This illustration also led to the famous ‘Ancient of Days’, frontispiece to Europe of 1794 (repr. Erdman Illuminated Blake 1974, p.156), in which the Creator in the guise of Urizen imposes a rational order on the universe. ‘The Ancient of Days’, although completely different in composition to ‘Newton’, is also related through having apparently been derived, as a deliberate visual counterblast, from A. Motte's frontispiece to the 1729 edition of Newton's Principia, in which Newton is elevated to the heavens. Another source, as Bindman suggests, may have been Blake's own commercial engraving after Stothard for the frontispiece to John Bonnycastle's An Introduction to Mensuration, and Practical Geometry, published in 1782 (Bindman 1978, no.2, repr.). The compasses, which are shown both in ‘Newton’ and ‘The Ancient of Days’, appear in Urizen, 1794, as one of the instruments created by Urizen to define the material world (Keynes Writings 1957, p.234); in The Song of Los, 1795, Urizen entrusts the ‘Philosophy of the Five Senses’ to Newton and Locke (Keynes 1957, p.246). If, as it appears at least in the Tate Gallery copy of the print, Newton is shown under water this is another symbol of materialism (Boime has drawn attention to Newton's comparison of himself to a boy playing on a sea shore, ‘diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, while the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me’). But Newton was also seen by Blake as contributing towards Man's redemption, if only by giving a tangible form to error; in Europe he blows ‘The Trump of the Last Doom’, one of the events leading up to the French Revolution (Keynes 1957, p.243).

Published in:

Martin Butlin, William Blake 1757-1827, Tate Gallery Collections, V, London 1990

Explore

- leisure and pastimes(3,435)

-

- art and craft(2,383)

-

- drawing(221)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- drapery(122)

- compasses(7)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- bending forward(353)

- sitting(3,347)

- man(10,453)

- male(959)

- individuals: male(1,841)

- educational and scientific(1,494)

-

- mathematician(33)

- scientist(81)