Joseph Beuys

‘Avant Garde Art: What’s Going Up in the 80’s?’. Edinburgh International Festival, The Richard Demarco Gallery

(1980)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Avant-garde is originally a French term, meaning in English vanguard or advance guard (the part of an army that goes forward ahead of the rest). It first appeared with reference to art in France in the first half of the nineteenth century, and is usually credited to the influential thinker Henri de Saint-Simon, one of the forerunners of socialism. He believed in the social power of the arts and saw artists, alongside scientists and industrialists, as the leaders of a new society. In 1825 he wrote:

We artists will serve you as an avant-garde, the power of the arts is most immediate: when we want to spread new ideas we inscribe them on marble or canvas. What a magnificent destiny for the arts is that of exercising a positive power over society, a true priestly function and of marching in the van [i.e. vanguard] of all the intellectual faculties!

The beginning of the avant-garde

Avant-garde art can be said to begin in the 1850s with the realism of Gustave Courbet, who was strongly influenced by early socialist ideas. This was followed by the successive movements of modern art, and the term avant-garde is more or less synonymous with modern.

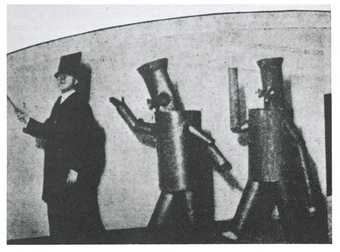

Some avant-garde movements such as cubism for example have focused mainly on innovations of form, others such as futurism, De Stijl or surrealism have had strong social programmes.

The development of the avant-garde

Although the term avant-garde was originally applied to innovative approaches to art making in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it is applicable to all art that pushes the boundaries of ideas and creativity, and is still used today to describe art that is radical or reflects originality of vision.

The notion of the avant-garde enshrines the idea that art should be judged primarily on the quality and originality of the artist’s vision and ideas.

Movers and shakers

Because of its radical nature and the fact that it challenges existing ideas, processes and forms; avant-garde artists and artworks often go hand-in-hand with controversy. Read the captions of the artworks below to find out about the shock-waves they caused.

Edgar Degas

Little Dancer Aged Fourteen

(1880–1, cast c.1922)

Tate

Georges Braque

Bottle and Fishes

(c.1910–12)

Tate

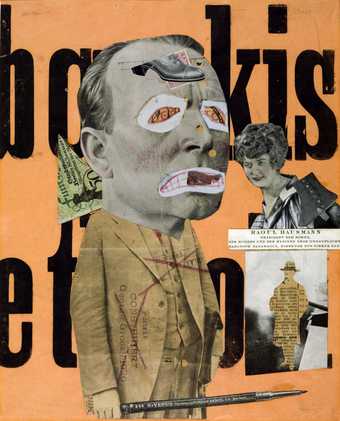

Raoul Hausmann

The Art Critic

(1919–20)

Tate

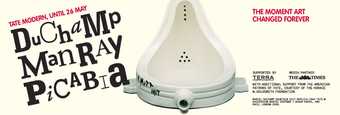

Marcel Duchamp

Fountain

(1917, replica 1964)

Tate

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024

Man Ray

Indestructible Object

(1923, remade 1933, editioned replica 1965)

Tate

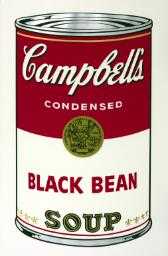

Andy Warhol

Black Bean

(1968)

Tate

© 2024 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London

Carl Andre

Equivalent VIII

(1966)

Tate

Rudolf Schwarzkogler

3rd Action

(1965, printed early 1970s)

Tate

© The estate of Rudolf Schwarzkogler, courtesy Gallery Krinzinger

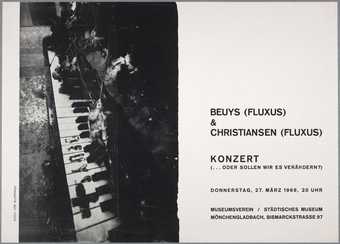

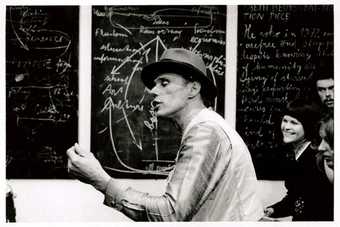

Joseph Beuys

Information Action 1972

Avant-garde art often has a social or political dimension to it. Joseph Beuys, who belonged to the avant-garde artist network Fluxus, used as his starting point the concept that everything is art, that every aspect of life can be approached creatively and, as a result, everyone has the potential to be an artist. Although a passionate and charismatic professor of art at Dusseldorf Academy his relationship with authority was stormy and he was dismissed in 1972.

Photo: Simon Wilson

Tate Archive Photographic Collection: Seven Exhibitions 1972

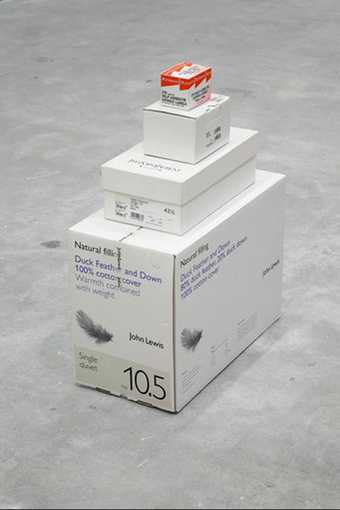

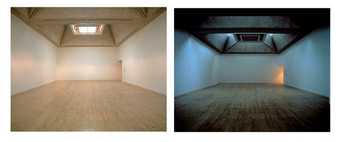

Martin Creed

Work No. 227

The lights going on and off 2000

From the mid-1960s conceptual artists have championed the idea and process of the artist over the art object. Martin Creed caused controversy in 2001 when he presented his conceptual Work No. 227 at Tate Britain. It consists of an empty gallery which alternates between being lit and plunged into darkness as the lights are turned on and off. The work prompted outrage. One gallery visitor threw eggs at the walls to register her disgust at the piece.

Photo: Tate Photography © Martin Creed