- Artist

- Jane Alexander born 1959

- Medium

- Fiberglass resin, plaster, synthetic clay, oil paint, acrylic paint, earth, found and commissioned garments and objects

- Dimensions

- Overall display dimensions variable

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by Tate’s Africa Acquisitions Committee, Tate International Council, Sir Mick and Lady Barbara Davis, Alexa Waley-Cohen, Tate Patrons, Tate Members and an anonymous donor 2016

- Reference

- T14629

Summary

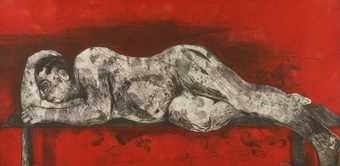

African Adventure 1999–2002 is an installation comprising thirteen individually titled figures, each of which has a specific placement on a large rectangular area of red Bushmanland earth that measures approximately eight by five metres. The two-legged figures are positioned on boxes, barrels or pedestals supported by steel plates concealed beneath the earth. Pangaman, the central figure in the tableau, is a life-size male figure made from oil-painted Hydrostone, positioned facing away from the entrance to the room. The figure is dressed from the waist down in found overalls and underwear, while his head is covered in a cloth. In his left hand he holds a South African-made machete. Forty-three sickles, eight machetes, eight model tractors and trailers and large agricultural cutting instruments lie on the earth around him, tied to his waist with shoe laces.

The first figure encountered when approaching the installation is Harbinger, an anthropomorphic character with a human body and monkey face, made from oil-painted reinforced Cretestone with found shoes and standing on an orange barrel. To the right of this there is a small seated female figure titled Girl with Gold and Diamonds. This figure, also made from oil-painted Cretestone, wears a Victorian silk christening dress and found underwear and shoes. She sits on a wooden chair and has two gold-plated bronze horns, three diamonds in a gold setting and wears a synthetic clay mask. Behind Girl with Gold and Diamonds there is a group of three small male figures titled Radiance of Faith. These fibreglass figures stand on found TNT explosive boxes and wear custom-made woollen suits, embroidered ties, and found shirts, shoes and underwear. Their faces have been obscured by synthetic clay masks which resemble different animals but cannot be identified as any one species.

Towards the centre of the tableau there are several more figures. Doll with Industrial Strength Gloves, a stuffed cloth doll on a wire armature with an oil-painted synthetic clay head and handmade Venetian gloves stitched to the body, is seated on a steel doll’s pushchair. Behind this figure Settler, an oil-painted reinforced Cretestone monkey-type figure wearing found shoes, sits in a small steel car. Young Man, made from fibreglass, painted in acrylic and wearing a custom-made suit and hat, found underwear, shoes and dark glasses, looks on. Interspersed with these figures, which each have human features, there are three further sculptures, which are more clearly animal-like: Ibis, an oil-painted synthetic clay bird-like animal with a long beak and dark shins; Beast, an oil-painted Cretestone figure on all fours with a tail and monkey-like face; and Dog, an oil-painted Cretestone sculpture which closely resembles a wild dog with rounded ears, dog collar and found black-backed jackal pelt draped over its back. At the far end of the tableau, an oil-painted synthetic clay figure titled Custodian sits on a wood and steel perch. The positioning of the half animal, half human-like forms in relation to each other and the theatrical staging are important elements in the work and the artist has provided a set of installation instructions which need to be followed in displaying the work.

The title African Adventure refers to a travel agency in South Africa that goes by the same name. Following South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994, the country quickly became a fashionable tourist destination and first port of call for those wishing to visit other sub-Saharan African countries. In Alexander’s work, the title is a comment on colonialism, identity, democracy and the residues of apartheid. The silent, tensely arranged forms speak of human failure, our inability to relate to each other, and a segregated and fragile society. The hybrid characters, neither human nor animal, are simultaneously emblems of monstrosity and oddly beautiful. They do not convey a particular moral or political position (often expected of work made in South Africa in the immediate post-apartheid era) but go back and forth between humanity and bestiality, realism and metaphor, naturalism and the uncanny.

Alongside the earlier Butcher Boys 1985−6 (South African National Gallery, Cape Town), African Adventure is considered one of Alexander’s most important works. Described as her most extensive project by historians Marten Ziese, Simon Njami and others, African Adventure is more physically and thematically expansive than Butcher Boys, which was a direct response to the abuses of power, torture and detention emblematic of the apartheid era. African Adventure brings together a number of themes the artist has explored previously and utilises many of the same techniques as earlier works. However, it is more enigmatic and, although rooted in the post-apartheid South African experience, is not defined solely by it. In an interview with Lisa Dent in 2012, Alexander said: ‘Much of what I consider while producing my work is globally pervasive, such as segregation, economic polarities, trade, migration, discrimination, conflict, faith etc’ (quoted in Dent 2012, accessed August 2013).

Further reading

Jane Alexander, exhibition catalogue, South African National Gallery, Cape Town 2002, reproduced pp.74–85.

Pep Subirós (ed.), Jane Alexander: Surveys (From the Cape of Good Hope), exhibition catalogue, Museum for African Art, New York 2011.

Lisa Dent, ‘Global Context: Q&A with Jane Alexander’, Art in America, 6 August 2012, http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/interviews/jane-alexander-cam-houston/, accessed August 2013.

Kerryn Greenberg

December 2013

Revised Zoe Whitley

May 2014

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.