- Artist

- Farah Al Qasimi born 1991

- Medium

- Photograph, inkjet print on paper

- Dimensions

- Image: 1003 × 751 mm

frame: 1022 × 768 × 31 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by the Middle East North Africa Acquisitions Committee 2022

- Reference

- P82696

Summary

This is one of a group of photographs in Tate’s collection by Farah al Qasimi that present interiors and scenes of striking colours, shimmering textures and graphic textiles. They were taken in the United Arab Emirates and the United States, countries between which the artist lives and works, playfully engaging with cultural signifiers, gendered expressions of identity and colonial legacies in the Middle East. Each photograph exists in an edition of five with two artist’s proofs.

Taken between 2016 and 2020, a number of the photographs capture moments in the homes of the artist’s relatives in the Emirates (Tate P82690–P82694). Through images of these private spaces that discreetly allude to the women and men inhabiting them, Al Qasimi offers a nuanced perspective on the gendered dynamics of social life in the country she grew up in. Through these colourful and often heavily decorated interiors, she conveys the material adornment of spaces as a performative, aspirational gesture, bound up with what she refers to as ‘the post-colonial hangover’ (conversation with Tate curators Nabila Abdel Nabi and Carine Harmand, 29 June 2020). Maximalist interiors and hyperbolically eclectic choices of decoration hint at the British colonial legacy in the United Arab Emirates and how this history has informed pervading ideas of taste and class.

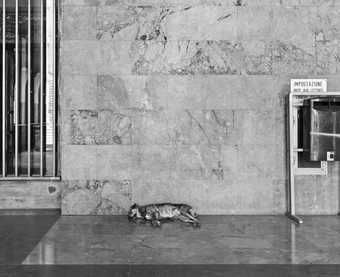

Blanket Shop 2019 (Tate P82695) and Woman in Leopard Print 2019 (Tate P82696) are part of Al Qasimi’s series Back and Forth Disco 2019, a commission of seventeen photographs for the Public Art Fund that captures details of local communities and small businesses familiar to Al Qasimi in New York. Originally aimed at being displayed in the public arena (shown across a hundred bus shelters in New York in 2020), these images emphasise the beauty to be found in the ordinary details of New York life.

In-betweenness and disorientation are at the heart of Al Qasimi's images. Playing with expectations, they intentionally blur geographic references and the boundaries between public and private space. In an interview with art editor Brendan Embser, Al Qasimi explained that, ‘all of the photographs have a confusing sense of location or geography that indicates that you are in a lot of in-between spaces, whether they’re immigrant communities in the U.S. or signs of colonial influence in the Middle East’ (quoted in Brendan Embser, ‘Why Farah Al Qasimi Has Her Eye on You’, Aperture, 21 April 2020, https://aperture.org/blog/farah-al-qasimi-interview-summer-open/, accessed 3 August 2020).

Al Qasimi often photographs the rooms and other living spaces of her female relatives in the Emirates. These places of intimacy, which are also locales for socialising, attest to a taste for visual excess and amalgamation of cultural references that is characteristic of Al Qasimi’s aesthetic. The environments portrayed in these photographs are a feature of some of her other works; certain scenes of her film Um Al Naar 2019, also in Tate’s collection (Tate T15937), were shot in the houses of her friends and relatives. Al Qasimi’s images appear carefully staged but offer an unexpected way to frame characters that undermines traditional ways of portrayal. All the photographs in Tate’s collection treat the human presence in an elusive, fragmented manner. A man’s head disappears in a cloud of vape smoke; an anonymous S is concealed behind the heavy blanket a woman is folding; gazes turn away from the camera or bounce back at it through mirrored surfaces. This ambiguous approach attests to the artist’s intention to respect the privacy of her subjects, yet in a seemingly contradictory way foregrounds their personal situation and individual presence in the photograph.

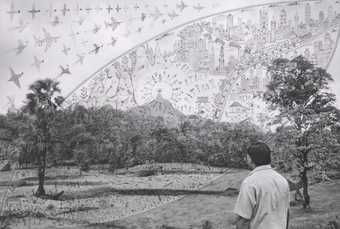

Al Qasimi has shown her photographs and film against a backdrop of images printed as vinyl wallpaper and this practice is a feature of some of her other work.

Further reading

Brendan Embser, ‘Why Farah Al Qasimi Has Her Eye on You’, Aperture, 21 April 2020, https://aperture.org/blog/farah-al-qasimi-interview-summer-open/, accessed 3 August 2020.

Carine Harmand

August 2020

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.