- Artist

- Eileen Agar 1899–1991

- Medium

- Plaster, fabric, shells, beads, diamante stones and other materials

- Dimensions

- Object: 570 × 460 × 317 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1983

- Reference

- T03809

Summary

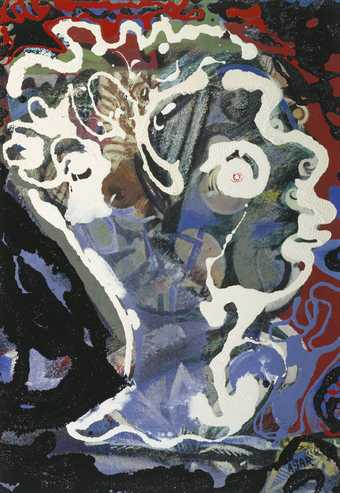

Angel of Anarchy is a sculpture by the Argentine-born British artist Eileen Agar. It comprises a plaster cast head covered with found materials and objects such as embroidered silk fabric, feathers, sea-shells, African beads and diamante stones. While some of the elements suggest facial features, others seem more like decorative accessories or jewellery. At times they could be read as either: for instance, feathers could be errant tufts of hair or part of an elaborate headdress. Similarly, the patterned fabric serves as skin for the face as well as a blindfold. This ambiguity creates allusions to seduction and submissiveness, although the accumulation of elements also appeals to the anarchy referenced in the title. Angel of Anarchy is displayed on top of a white pedestal under a protective Perspex case due to its fragile condition.

The work was created by Agar in 1936–40. Agar was a friend of Henry Moore and she would accompany him on visits to the ethnographic collections at the British Museum in London, whose collection of African sculpture influenced both artists. In contrast to Moore, Agar worked primarily in plaster, which she chose because ‘bronze was too expensive’. In addition, rather than making preliminary drawings, Agar used found materials, applying them directly onto the head. The white plaster cast in this sculpture is from a modelled clay bust of the artist’s future husband Joseph Bard.

The sensuous and uncanny nature of Angel of Anarchy relates to surrealism, which Agar was deeply interested in. Agar was one of the few women artists to become a member of a surrealist group in a cultural world dominated by men. In 1936 she joined the British Surrealist Group and signed the group’s inaugural manifesto. In that same year she exhibited her work at the International Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries in London, which marked the emergence of surrealism in England and was organised by Roland Penrose, David Gascoyne and Herbert Read in collaboration with French surrealists such as André Breton and Paul Eluard.

Art historian Anna Gruetzner notes that Tate’s Angel of Anarchy is the second version of an earlier yet substantially different sculpture with the same title made by Agar between 1934 and 1936. The first version, now lost, was initially shown in the exhibition Surrealist Objects and Poems at the London Gallery in 1937 and was subsequently sent to the International Surrealist Exhibition at the Galerie Robert in Amsterdam in the spring of 1938, but was never returned (Nairne and Serota, p.115). An illustration of the first version was reproduced on the cover of the exhibition catalogue Surrealist Objects and Poems in 1937. Agar’s piece Angel of Mercy 1934, along with the two versions of Angel of Anarchy, constitute the sculptural element of the artist’s practice, which mainly focused on painting and photography.

According to Patricia Allmer, art historian and curator of the exhibition Angels of Anarchy: Women Artists and Surrealism (Manchester City Art Gallery, Manchester, 2009), Agar’s Angel of Anarchy addresses issues of gender identity by ‘enacting a man’s becoming-woman’ (Allmer 2010, p.26). Allmer goes on to suggest that ‘the angel is one of the key symbols of women surrealists’, standing for ‘hybridity and becoming’, and as such enabled women surrealists to ‘challenge patriarchy’ and ‘to overcome its own blindness’ towards women (Allmer 2010, pp.26–7). Allmer also suggests that in accordance with the revolutionary spirit of surrealism, Agar’s title, Angel of Anarchy, ‘could be construed as a surrealist programme in miniature, with its promise of an outrageous fusion of the sacred and the dissident’ (Allmer 2010, p.43).

Further to the gender critique that Allmer highlights, there were other important political contexts surrounding the sculpture since, as Gruetzner has observed, ‘English surrealism developed in a strongly political climate’. Gruetzner continues:

There was an enormous sympathy for the Spanish Anarchists within the English group and several manifestos were issued on their behalf. In 1937 Herbert Read, who was the ‘angel of anarchy’ and author of Surrealism, published by Faber and Faber in 1936, announced his commitment to Anarchism and published The Necessity of Anarchism. But the outbreak of the Second World War complicated and confused these political causes and when the second version of The Angel of Anarchy was made in 1940, Eileen Agar added a blindfold because the future was so uncertain.

(Gruetzner in Nairne and Serota, pp.113–15.)

Further reading

Sandy Nairne and Nicholas Serota (eds.), British Sculpture in the Twentieth Century, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1981, pp.113–15, reproduced p.115.

Penelope Rosemont (ed.), Surrealist Women: An International Anthology, London 1998.

Patricia Allmer (ed.), Angels of Anarchy: Women Artists and Surrealism, exhibition catalogue, Manchester City Art Gallery, Manchester 2009, pp.26, 43, reproduced p.88.

Natasha Adamou

March 2016

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

The blindfolded Angel of Anarchy is loosely based on an earlier painted plaster head. Agar stated that with this new work she wanted to create something ‘totally different, more astonishing, powerful ... more malign’. It suggests the foreboding and uncertainty that she felt about the future in the late 1930s. Believing that women are the true surrealists, Agar wrote: ‘the importance of the unconscious in all forms of Literature and Art establishes the dominance of a feminine type of imagination over the classical and more masculine order.’

Gallery label, October 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

T03809 ANGEL OF ANARCHY 1936–40

Fabric over plaster and mixed media 20 1/2 × 12 1/2 × 13 1/4 (520 × 317 × 336)

Inscribed ‘AGAR/ANGEL OF ANARCHY’ on back of neck

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1983

Prov:

Purchased from the artist by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1983

Exh:

Eileen Agar, Retrospective Exhibition, Commonwealth Art Gallery, September–October 1971 (18); Dada and Surrealism Reviewed, Hayward Gallery, January–March 1978 (14.3, repr.); Weich und Plastich, Soft-Art, Kunsthaus, Zurich, November 1979–February 1980 (repr. p.77); British Sculpture in the Twentieth Century, part 1, Whitechapel Art Gallery, September–November 1981 (177, repr.); The Women's Art Show, 1550–1970, Castle Museum, Nottingham, May–August 1982 (83, repr. in col.); Milestones in Modern British Sculpture, Mappin Art Gallery, Sheffield, October–November 1982 (10); La planète affolée. Surréalisme, dispersion et influences, 1938–1947, Centre de la Vieille Charité, Marseilles, April–June 1986 (1, repr. in col. p.170)

Lit: Paul Nash, ‘Artists and their work - 4. Surrealism: Objects and Pictures’, BBC television, 21 January 1938; Anna Gruetzner, ‘The Surrealist Object and Surrealist Sculpture’, British Sculpture of the Twentieth Century, Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1981, pp.113–23 (repr. p.115); Penny McGuire, ‘Surreal Life Legend’, Observer Magazine, 20 November 1983, pp.20–5 (repr. p.21); Frances Spalding, British Art Since 1900, 1986, p.117 (repr. p.119).

Also repr: Du, 1983, 1, p.53

This head is a second and quite different version of a sculpture of the same title which was made by Eileen Agar in 1934–6 and lost shortly afterwards, never being returned from an exhibition in Amsterdam in June 1938.

The lost first version was reproduced on the cover of the exhibition catalogue Surrealist Objects and Poems, London Gallery, November 1937 (photographed by the artist) where it was first exhibited. It is listed there in the section titled ‘Surrealist Objects’ as ‘Angel of Anarchy’, along with three other works by Agar. It is a plaster head of a man, with coloured paper and paper doilies, green feathers and black Astrakhan fur attached to it, not painted except on the lips. This head Agar made in the first place in clay, at her studio in Earl's Court, as a portrait of Joseph Bard (her future husband). Bard, a Hungarian and a poet, had been editor of the art magazine The Island (1931–2), which was financed by Agar and organised by pupils of Leon Underwood at his school in Brook Green, which both she and Bard attended for drawing. Underwood had already modelled a portrait head of Bard, and Agar felt that she could improve on it. Her sculpture was made from sittings with the model, and is severely geometrical.

Agar sent her clay to be cast in plaster, and received two copies, one of which she then covered with ‘whatever came to hand’ (conversation of 18 May 1984), in part in order to hide its whiteness. This was the first sculpture she had made, although she had been in contact with modern sculptors since visiting Brancusi's studio in Paris in 1930, and she had bought a carving by Henry Moore in about 1932. She did not know Surrealist artists personally before the International Surrealist Exhibition in London in June 1936, and was invited to show in this by Herbert Read. She exhibited there three paintings and five ‘objects’, the latter now only known by title. Following this exhibition she made both the first version of ‘Angel of Anarchy’ and another dressed up head ‘Rococo Cocotte’ (repr. Anna Greutzner, op.cit., p.117), although in this the head itself was not made by the artist. At the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme, Galerie Robert, Amsterdam (June 1938) the former was listed as ‘L'ange de l'anarchie (1934–1936)’.

The first version retained its character as a portrait of Joseph Bard, but was associated by Agar in its title with Herbert Read, the critic who had been one of the organisers of both the 1936 and 1937 Surrealist exhibitions in London:

... the title was suggested by the fact that Herbert Read was known to the Surrealists as a benign anarchist, so that is how I thought of the title ‘Angel of Anarchy’, for anarchy was in the air in the late thirties (note from the artist, 18 May 1984).

The title was invented after the work was made, and partly by chance, as Agar recalled hearing some builders in the studio mentioning the wood ‘Archangel pine’, while she was thinking what to call it.

At the start of the war it was evident that the sculpture would not be returned from Amsterdam:

so in 1940 I started covering the second plaster head (now in the Tate). This one I decided should be totally different, more astonishing, powerful (and forgetting about a portrait) more malign. Although the same base it has ostrich feathers for the hair, a Chinese silk blindfold, a piece of bark cloth round the neck and African beads at the back of the head, as well as occasional osprey feathers and a diamanté nose (note of 18 May 1986).

The African tapa cloth and the bead fringe were bought for this purpose in antique shops, and most of the other materials were supplied from Agar's mother's wardrobe.

The head was stored by the artist and not retrieved until William Seitz, the curator of ‘The Art of Assemblage’ exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (1961) enquired for her pre-war sculpture and collages.

Published in:

The Tate Gallery 1982-84: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1986

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- figure(2,270)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- assemblage / collage(47)

- found object / readymade(2,631)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

- body(4,878)

-

- head / face(2,497)

- social comment(6,584)

-

- gender(1,689)