Sir John Everett Millais, BtOphelia 1851–2Tate

Beauty as Protest 1845–1905

16 rooms in Historic and Early Modern British Art

The men and women of the Pre-Raphaelite circle question mainstream Victorian culture and ideas

In 1848, revolutions all over Europe spread the spirit of reform across the continent. Three art students, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt, launch a revolution in art. Rossetti is the son of an Italian revolutionary. Hunt worked in a textile warehouse for the popular political activist, Richard Cobden. Hunt and Millais watch Chartist campaigners march on parliament to petition for workers’ rights. In November 1848, the trio create a radical artistic group called the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

The Pre-Raphaelites reject the academic art of the Royal Academy, which holds certain historical subjects and styles in high esteem. They look for authenticity in art of all periods, but seek relevance to their modern times. The seven members, alongside the men and women in their wider circle, choose subjects that cast a light on social issues. They update stories from the Bible, Shakespeare and medieval poetry. They paint real people, objects and settings. Later on, their art becomes concerned with beauty and imagined worlds.

Walter Crane, author William Morris, Monopoly; or, How Labour is Robbed 1890

1/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Jane Morris, Jenny Morris, William Morris, Honeysuckle embroidery 1880

2/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

William Morris, News from Nowhere 2015

3/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Morris & Co. (London, UK), Pipernel design, wallpaper book 1917–1939

4/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

John William Inchbold, Gordale Scar, Yorkshire exhibited 1876

Inchbold, who was born in Leeds, came under the influence of the Pre-Raphaelites in the early 1850s. He established himself as one of the leading landscapists of the movement but by the end of the decade had adopted a broader, more atmospheric approach, as shown here. When it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy it was accompanied by lines from Wordsworth’s sonnet ‘Gordale’ of 1818: ‘... when the air/Glimmers with fading light .../Then, pensive Votary!, let thy feet repair/To Gordale-chasm, terrific as the lair/where the young lions couch; ...’.

Gallery label, November 2016

5/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Henry Wallis, The Room in Which Shakespeare Was Born 1853

Wallis launched his career exhibiting a sequence of paintings of interior scenes connected with the life of playwright William Shakespeare (1564-1616). This one shows Shakespeare’s birthplace in Stratford-upon-Avon. It is based on a biography by Charles Knight written in 1842. It describes ‘the mean room, with its massive joists and plastered walls, firm with ribs of oak’. Wallis has painted the room in detail, including every nail securing the floorboards. He has also taken note of Knight’s passage describing how ‘hundreds amongst the hundreds of thousands by whom that name is honoured have inscribed their names on the walls of the room.’

Gallery label, June 2019

6/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Thomas Gaskell, Gaskell Wall Clock 1848

7/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Thomas Woolner, Puck 1845–7

Puck is a mischievous invisible fairy in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Thomas Woolner has illustrated a scene here from an ‘Imaginary Biography’ of Puck. He alights on a mushroom to save a sleeping frog from a hungry snake. The sculpture captures the instant before a sudden movement – as Puck touches the frog with his foot it will jump away just before the snake attacks.Ideal or poetic subjects drawn from literature, mythology or history, were highly regarded by sculptors in the mid-nineteenth century.

Gallery label, July 2007

8/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Walter Crane, author William Morris, Useful Work Versus Useful Toil 1893

9/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Ford Madox Brown, Jesus Washing Peter’s Feet 1852–6

This picture illustrates the biblical story of Christ washing his disciples’ feet at the Last Supper. It has an unusually low viewpoint and compressed space. Critics objected to the picture’s coarseness – it originally depicted Jesus only semi-clad. This caused an outcry when it was first exhibited and it remained unsold for several years until Ford Madox Brown reworked the figure in robes. Brown was never invited to join the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood but he was a close associate of the group. Several members modelled for the disciples in this picture and the critic FG Stephens sat for Christ.

Gallery label, November 2016

10/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

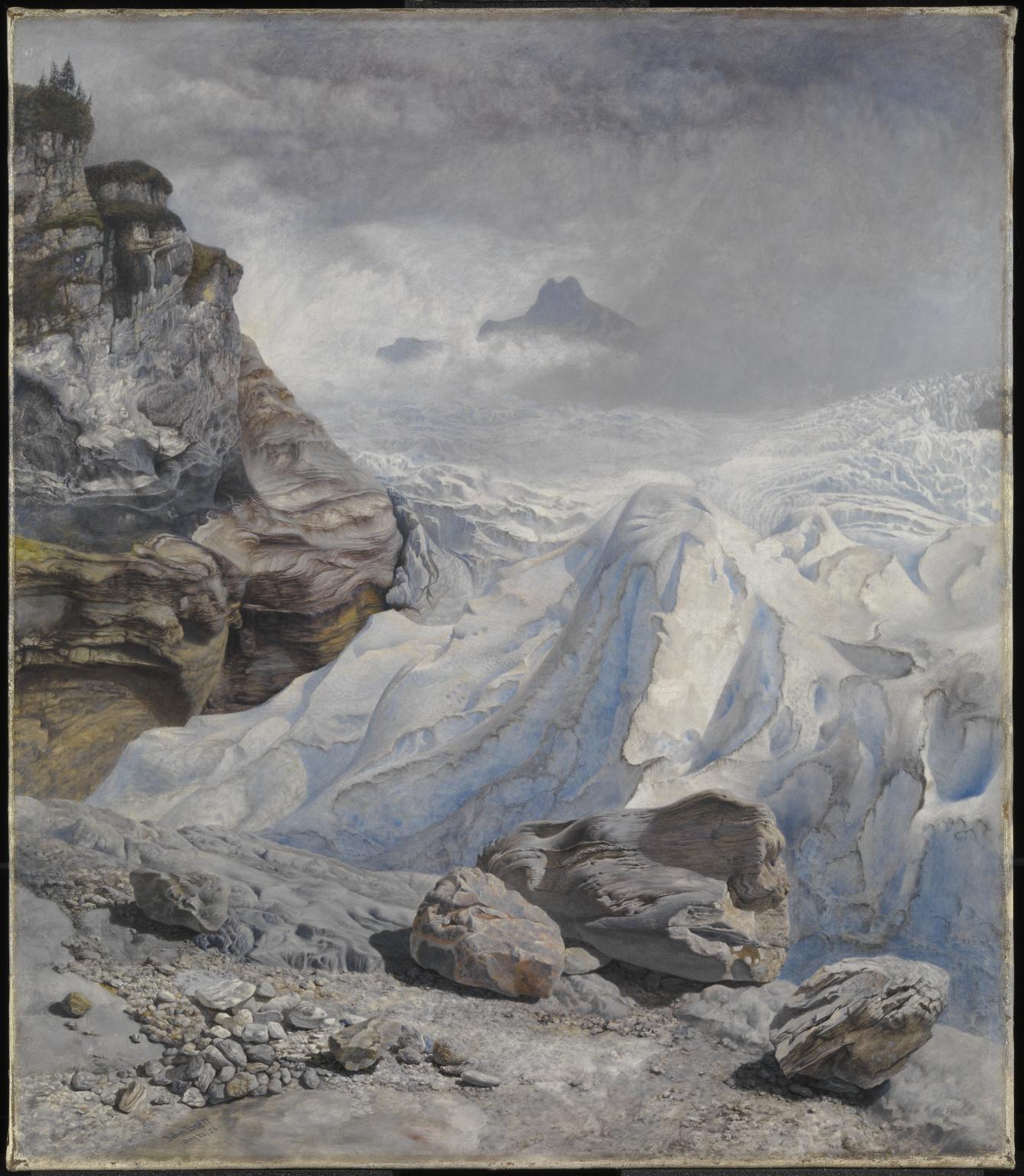

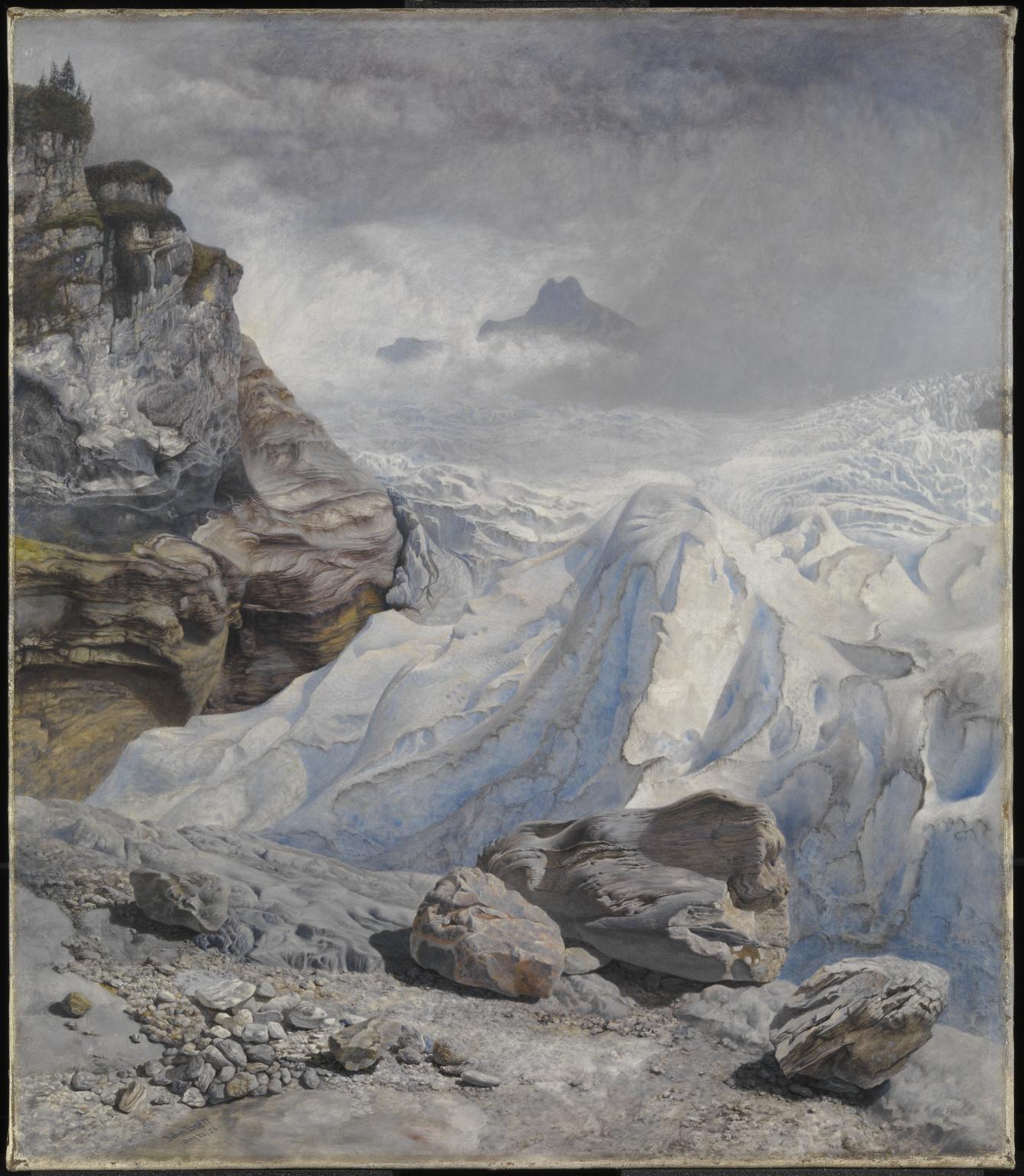

John Brett, Glacier of Rosenlaui 1856

The Rosenlaui glacier is at the foot of two spectacular Alpine peaks, including the Dossenhorn, and yet they are not the focus here. Instead Brett makes a meticulous study of different types of rocks and pebbles, offset by the dense blue white folds of the glacier itself. This attention to the detail as well as enormity of nature reflects the critic John Ruskin’s sentiment that a small stone was ‘a mountain in miniature’. Brett had travelled to Switzerland after reading Ruskin’s Of Mountain Beauty and met the artist John William Inchbold who influenced him to ‘paint all I could see’.

From William Wordsworth, ‘The Prelude’, Book 6, Cambridge and the Alps, 1850

... The immeasurable heightOf woods decaying, never to be decayed,The stationary blasts of waterfalls,And in the narrow rent at every turnWinds thwarting winds, bewildered and forlorn,The torrents shooting from the clear blue sky,The rocks that muttered close upon our ears,Black drizzling crags that spake by the way-sideAs if a voice were in them, the sick sightAnd giddy prospect of the raving stream,The unfettered clouds and regions of the

Heavens,Tumult and peace, the darkness and the light –Were all like workings of one mind, the featuresOf the same face, blossoms upon one tree;Characters of the great Apocalypse,The types and symbols of Eternity,Of first, and last, and midst, and without end.

Gallery label, March 2010

11/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

William Holman Hunt, Claudio and Isabella 1850

This scene represents a moment of complex moral dilemma for Claudio and Isabella, characters from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure. Claudio has been sentenced to death by Angelo, deputy to the duke of Vienna. He can only be saved if his sister, Isabella, sacrifices her virginity to Angelo. Claudio’s awkward pose draws attention to his prison shackles. The apple blossom blown by the wind at his feet symbolises his readiness to buy his own reprieve with Isabella’s chastity. Her white habit emphasises her purity. Holman Hunt summarised the moral of his picture as: ‘Thou shall not do evil that good may come.’

Gallery label, November 2016

12/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Frederic George Stephens, The Proposal (The Marquis and Griselda) c.1850

This is a scene from The Clerk’s Tale, one of Geoffrey Chaucer’s fourteenth-century Canterbury Tales. The marquis of Saluzzo has fallen in love with a poor but beautiful peasant girl, Griselda, and is proposing marriage to her. He goes on to subject her to a series of appalling trials to test her love. But Griselda is patient and eventually wins his devotion.The background of this picture was painted from life in the kitchen of the rural lodgings that Stephens shared with his friends Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, at Knole in Kent.

Gallery label, July 2007

13/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale, The Châtelaine exhibited 1904

The Châtelaine (a French word for a noble woman who is mistress of a castle) is a polychrome, gilded statuette encrusted with semi-precious stones, set on a wooden base with turrets at its four corners and decorated with small Italianate landscapes on all four of its sides. Made of finely modelled plaster, the sculpture is richly patterned, painted and patinated. It represents a noble woman wearing a medieval ‘Balzo’ headdress and an opulent black and gold damask dress lined with red. Her estate is signified by a prominent set of heavy keys hanging from the green purse on her right side. Her face expresses sorrow and her hands are clasped in prayer or anguish. Despite the French title of the work, the figure’s style of dress appears to be Florentine, which is in accord with the Tuscany landscapes that are painted with gold leaf on the wooden base of the sculpture, in the manner of the so-called ‘predella’ scenes situated below sixteenth-century altarpieces. One of them represents a walled city, another a property with cypress trees; a third depicts a more generic landscape and the last one a shore approached by several ships.

14/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Ford Madox Brown, The Hayfield 1855–6

Brown painted this landscape directly from nature. The setting is the Tenterden estate at Hendon, north London, looking east at twilight. He finished the final details in his studio, adding a self-portrait in the lower left corner. The effect he sought to capture was the way in which the brown hay was made to appear almost pink by contrast with the dense green grass. After it was finished his dealer rejected it on the grounds that he had never seen hay of this colour. Brown later retouched the painting before selling it to his friend and fellow artist William Morris.

Gallery label, November 2016

15/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Henry Alexander Bowler, The Doubt: ‘Can these Dry Bones Live?’ exhibited 1855

This young woman, leaning on the gravestone of a man called John Faithful, is contemplating religious doubt. In particular, the Christian belief that the dead will be resurrected on the Day of Judgement. Long-standing religious beliefs were being disrupted at the time this was painted. New scientific publications explored theories of evolution, challenging literal readings of the Bible. Her question appears to be answered by the growing chestnut tree and the stone at its base, carved with the word Resurgam’, which translates as ‘I shall rise again’. The blue butterfly on the skull symbolizes the human spirit.

Gallery label, August 2018

16/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Sir John Everett Millais, Bt, Ophelia 1851–2

This work shows the death of Ophelia, a scene from Shakespeare’s play Hamlet. Traumatised when Hamlet breaks off their betrothal and accidentally kills her father, she allows herself to fall into a stream and drown. The flowers she has been collecting symbolise her story, the poppies representing death. Millais painted the lonely setting leaf-by-leaf over many months by the Hogsmill River, Surrey. Afterwards, the artist, poet and model Elizabeth Siddall posed in a wedding dress in a bath of water at Millais's studio. Through the painting, Millais critiqued the Victorian practice of occasionally arranging marriages for money and status.

Gallery label, March 2022

17/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

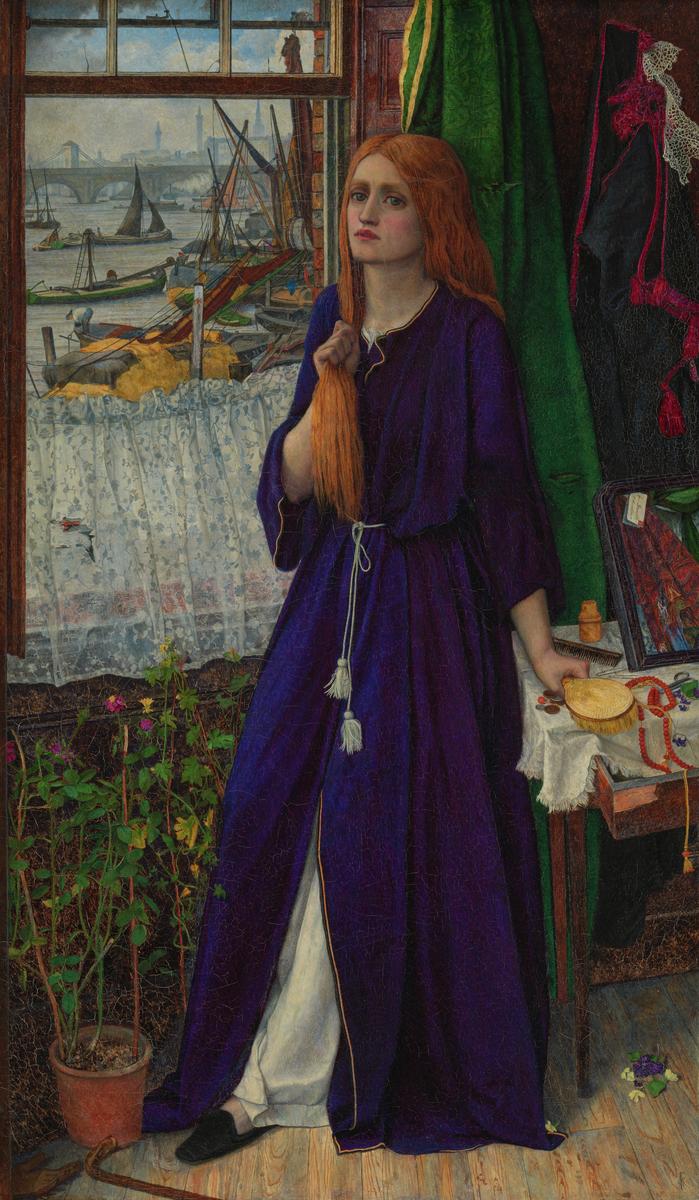

William Morris, La Belle Iseult 1858

The inspiration for this painting was Thomas Malory's 'Morte d'Arthur' (1485), in which Guinevere's adulterous love for Sir Lancelot is one of the central themes. The model is Jane Burden who became Morris's wife in 1859, and also appears in Rossetti's 'Proserpine' displayed nearby. She was 'discovered' by Morris and Rossetti when they were working together on the Oxford Union murals, the subject matter for which was also taken from Malory. The painting is essentially a portrait of her in medieval dress. It is a splendid expresion of the intense medieval style prevailing in Rossetti's circle in the late 1850s, with its emphasis on pattern and historical detail. This is Morris's only completed oil painting.

Gallery label, September 2004

18/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

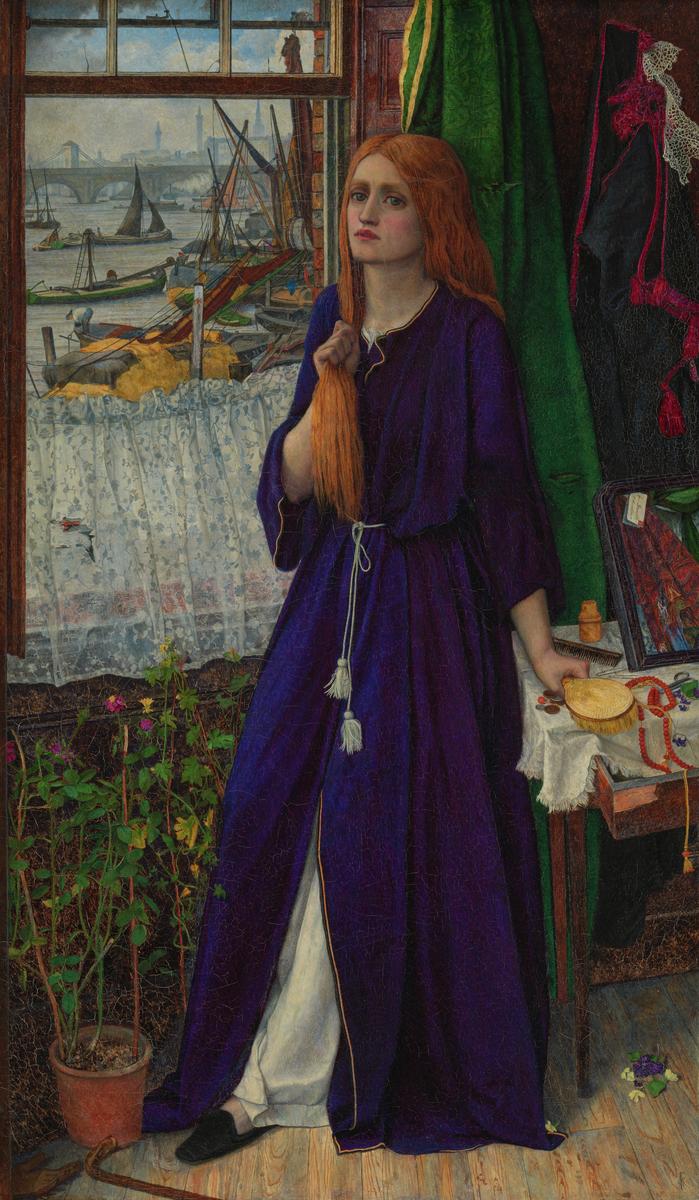

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, Thoughts of the Past exhibited 1859

This modern-life picture shows a prostitute in her lodgings overlooking the Thames. Her situation is indicated by the shabby interior with jewellery and money strewn across her dressing table, and the man’s glove and walking stick on the floor. Waterloo Bridge and Hungerford Bridge are shown in the distance straddling the busy polluted river. A sickly-looking plant by the woman’s side suggests her impending doom.

Gallery label, November 2016

19/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

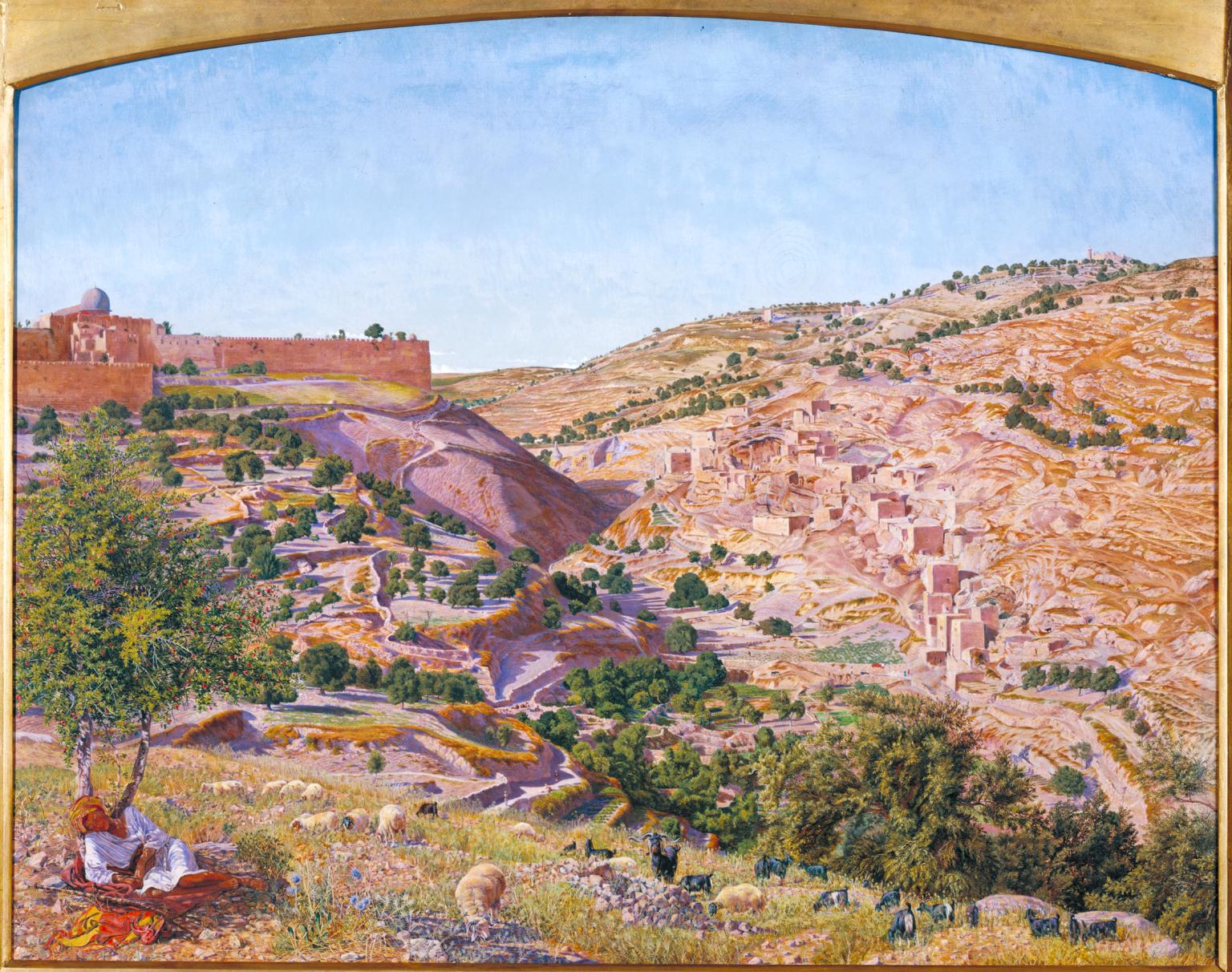

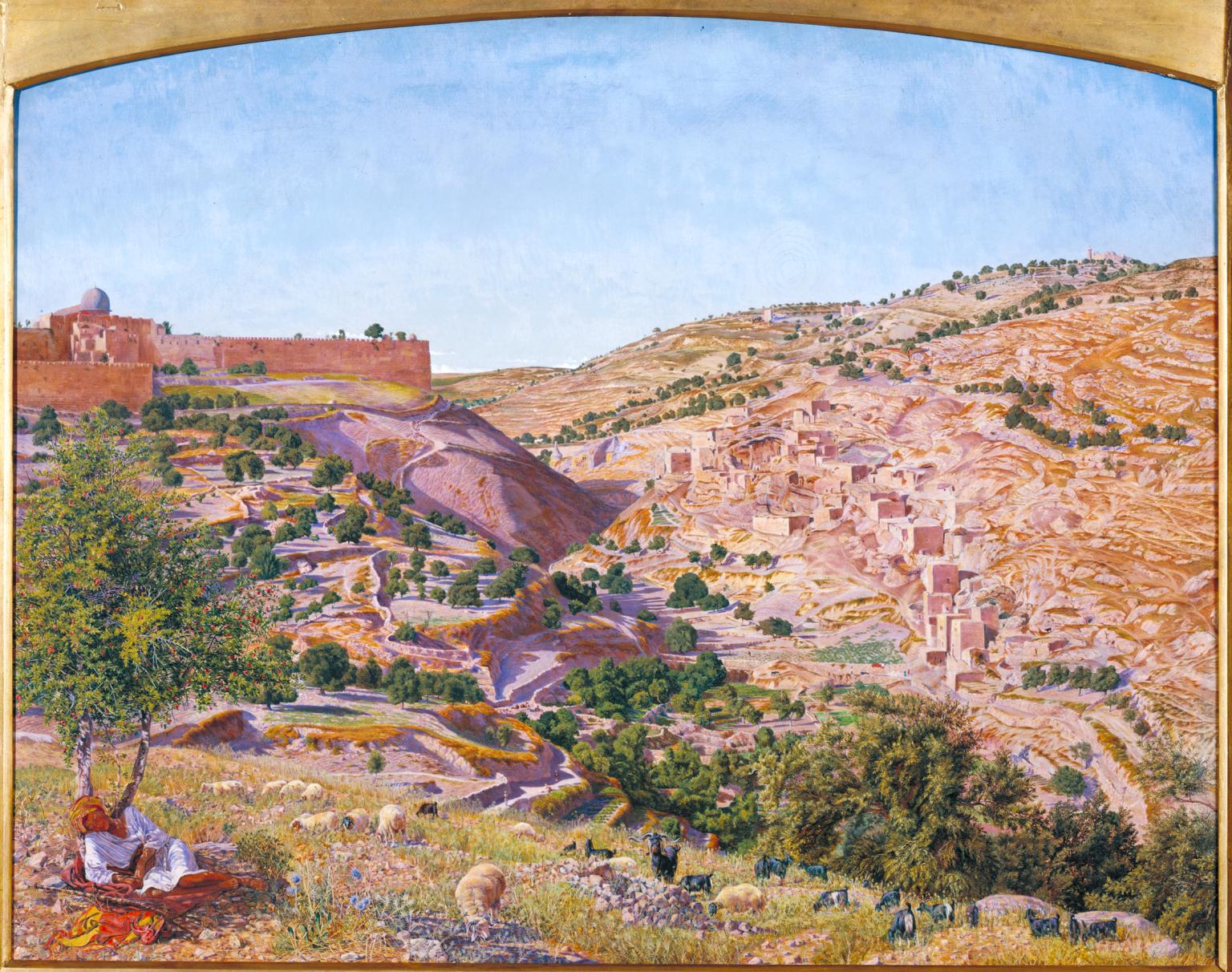

Thomas Seddon, Jerusalem and the Valley of Jehoshaphat from the Hill of Evil Counsel 1854–5

Seddon and his friend Holman Hunt journeyed to the Holy Land in 1854, to bring greater authenticity, spiritual and topographical, to their religious works. This view, painted south of Jerusalem, shows the Mount of Olives and the Garden of Gethsemane, the site of Christ’s anguish before the Crucifixion. The valley of Jehoshaphat was also believed to be where the Last Judgement would take place. Unlike John Martin’s apocalyptic visions, displayed nearby, Seddon represents the site in painstaking, sun-lit detail, paralleling the art critic John Ruskin’s remarks that ‘in following the steps of nature’, artists were ‘tracing the finger of God.’

Gallery label, March 2010

20/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Martha Darley Mutrie, Wild Flowers at the Corner of a Cornfield c.1855–60

This medium-sized oil painting depicts wildflowers, grasses and weeds growing on a bank on the edge of a cornfield. The large, white, trumpet-shaped flowers in the centre-left of the composition are the flowers of bindweed, the leaves and tendrils of which can be seen on the left of the bank. In the centre are thistles with their purple flowers and fluffy white seeds. Towards the top are the small blue cornflowers, while at the bottom there is the small yellow flower of lesser celandine. Elsewhere on the bank you can see the dark-brown prickly stems of a bramble, ferns, grasses and ivy. A large, blue, male Emperor dragonfly flies in the sky over the bank. A few ears of corn are shown on the far left of the composition, where a small gap reveals a view to the cornfield and wider landscape beyond.

21/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Rosa Triplex 1867

triple portrait of Charles I by Van Dyck. Rossetti's

Gallery label, August 2004

22/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Henry Wallis, Chatterton 1856

This highly romanticised picture created a sensation when it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1856. Thomas Chatterton was a poet whose ‘gothic’ writings, melancholy life and youthful suicide fascinated artists and writers of the 19th century. At an early age, he wrote fake medieval histories and poems, which he copied onto old parchment and passed off as manuscripts from the Middle Ages. The fraud was later discovered. In London he struggled to earn a living writing tales and songs for popular publications. Penniless, he took his own life by swallowing arsenic at the age of 17.

Gallery label, November 2016

23/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

John Frederick Lewis, Study for ‘The Courtyard of the Coptic Patriarch’s House in Cairo’ c.1864

The Coptic Church is the ancient Orthodox Christian Church of Egypt. This study of the patriarch’s house was executed after Lewis’s return from Egypt in 1851, from the sketches he brought back. The picture highlights Lewis’s skill in depicting figures and setting with careful attention to light and shade, produced here by the top-lit courtyard. Lewis caused a sensation when he exhibited one of his Near Eastern scenes in London in 1850. John Ruskin admired his attention to detail, claiming that in truth-to-nature he ranked alongside the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Gallery label, November 2016

24/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Rebecca Solomon, A Young Teacher 1861

25/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Ford Madox Brown, Chaucer at the Court of Edward III 1856–68

This picture is a replica of Ford Madox Brown’s largest and most ambitious painting, exhibited in 1851. It was significant for its portrayal of natural sunlight and was his first attempt ‘to carry out the notion ... of treating the light and shade absolutely, as it exists at any one moment, instead of approximately or in generalized style’. This pursuit of ‘truth to nature’ was consistent with Pre-Raphaelite ideals, as was his careful workmanship. The picture’s subject, Geoffrey Chaucer, reflects the growing popularity with artists of English literature instead of more conventional classical myths and biblical tales.

Gallery label, November 2016

26/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Sancta Lilias 1874

This is the abandoned first version of one of Rossetti’s most important pictures, The Blessed Damozel (1875–8). He first treated the subject in a poem which, inspired by Dante’s love for Beatrice, describes a dead woman’s yearning for her still-living lover. In the completed painting, Rossetti shows the Damozel looking down on her beloved from Heaven; this is the scene shown here. Rossetti’s fascination with the separation imposed by death proved eerily prophetic when his wife Elizabeth Siddall died of an overdose of laudanum in 1862.

Gallery label, November 2016

27/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

John Brett, Lady with a Dove (Madame Loeser) 1864

Jeannette Loeser, the subject of this portrait, was romantically involved with John Brett until the spring of 1865. The portrait was largely painted in Rome in the early months of 1864, and completed in London in August that year. The wing of the dove echoes the curved outline of the sitter’s skirt, and the dove motif is repeated in the mosaic brooch on her shoulder. Each corner of the frame is decorated with a winged cherub that looks into the picture as if in admiration of her beauty.

Gallery label, November 2016

28/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Sir John Everett Millais, Bt, Christ in the House of His Parents (‘The Carpenter’s Shop’) 1849–50

This picture was exhibited with words from the Old Testament, often seen as prefiguring Christ’s Crucifixion: ‘And one shall say unto him, What are these wounds in thine hands? Then shall he answer. Those with which I was wounded in the house of my friends.’ Millais based the setting on a real carpenter’s shop. Symbols of the Crucifixion figure prominently: the wood, the nails, the cut in Christ’s hand and the blood on his foot. Millais was viciously attacked in the press for showing the holy family as ‘ordinary’. Charles Dickens described Christ as ‘a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-haired boy in a night-gown.’

Gallery label, November 2016

29/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Joanna Mary Wells, Gretchen 1861

This picture alludes to a central scene in Faust, the tragic play published by German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in the early 19th century. In the play, Gretchen, confused, seduced and pregnant by Faust, seeks solace in church. The sitter for the work was probably Wells’s nursery maid. Women artists had limited access to models at the time. Joanna Wells (née Boyce) had established a reputation during the 1850s as a painter of portraits, genre and landscape. She also wrote art reviews for the Saturday Review. Her career ended prematurely at the age of thirty. Wells herself was pregnant when she began this painting. She died shortly after the birth and the picture was left unfinished.

Gallery label, December 2020

30/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Art in this room

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

You've viewed 6/30 artworks

You've viewed 30/30 artworks